eBook - ePub

Policy Issues in the Evolving International Monetary System

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Policy Issues in the Evolving International Monetary System

About this book

NONE

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Publisher

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUNDYear

1992eBook ISBN

9781557752345Part I: Mechanisms for Promoting Global Monetary Stability

I Introduction

The purpose of this part of the study is to consider the prospects for achieving greater stability in the international monetary system. In line with a number of other recent studies,1 an underlying presumption is that the key currencies in the system during the period ahead will be those of the United States, Japan, and the European Community (EC).

Section II begins by addressing developments in the world economy and their implications for the evolution of the system. A review of changes in relative economic size emphasizes that the major industrialized regions of the world have become significantly more symmetric over the past three decades. A review of relative inflation performance underscores that each of the three largest countries has demonstrated the ability to provide a nominal anchor. Developments in the international use of currencies and patterns of regional integration reinforce the impression that the evolution toward a multicurrency world is unlikely to be reversed. Developments in the provision of international liquidity suggest that the rapid expansion of private credit markets requires a rethinking of the role that the official sector should play in promoting the smooth functioning of the international liquidity system.

Section III discusses apparent problems with the present system. The problems include (1) undisciplined or ineffective national policies (fiscal, monetary, and structural); (2) excessive swings in real exchange rates; (3) limited credibility in efforts to manage exchange rates; and (4) deficiencies in the international liquidity system.

Section IV then considers what can be done about the first three of these problems, focusing on (1) measures to strengthen national policy making; (2) efforts to enhance multilateral surveillance and policy coordination; and (3) changes in the nature of exchange rate commitments. These issues are analyzed primarily as they apply to the largest industrial countries, which are relied upon to provide nominal anchors for the world economy.

An underlying theme of the paper is that the problems with the present international monetary system are largely a reflection of weaknesses that go beyond exchange rate arrangements per se. By the same token, progress toward greater exchange rate stability can be achieved within a system in which exchange rate commitments are tailored to the characteristics and circumstances of individual countries.

II Developments in World Economy and Implications for the International Monetary System

Changes in Relative Economic Size

One of the most important developments in the world economy over the past 30 years has been the trend toward greater symmetry in economic size among the industrialized countries of North America, Europe, and the Asia and Pacific region. The relative economic size of North America has declined, implying a much greater degree of interdependence for the United States, while Europe has taken major strides toward economic integration and the economies of Japan and other Asian countries have expanded rapidly. This trend toward greater symmetry in economic size has brought with it a greater sharing of economic leadership. Such evolution suggests that attempts to recreate a system of the Bretton Woods type with a single hegemon would not be viable.

Several indicators of relative economic size are shown in Table 1. The U.S. share of world output is now about 25 percent, down from more than 40 percent at the beginning of the 1960s, while Japan’s share has risen from about 4 percent to 11 percent. The U.S. share of world trade is currently less than 14 percent, not much lower than it was three decades ago; but relative trade shares have changed considerably as Japan’s share has risen from 4 percent to nearly 8 percent. The industrial countries of Europe now produce one third of the world’s output, slightly more than the share generated by the United States and Canada combined, and about twice the amount provided by Japan, Australia, and New Zealand. Industrial Europe also accounts for nearly half of world trade,2 while North America generates less than 20 percent and Japan, Australia, and New Zealand about 10 percent. For industrial and developing countries combined, the Western Hemisphere accounts for 21 percent of world trade, the Asia and Pacific region for 23 percent, Europe for 50 percent, and Africa and the Middle East for 6 percent.

Table 1. Relative Economic Size1

(In percent)

1 Country groupings are consistent with the classification in IMF publications, which divide the developing countries into five areas: Africa, Asia, Europe, Middle East, and Western Hemisphere. Excluded from the world total are the output and trade of the country group “U.S.S.R. and other nonmembers n.i.e.” as defined in Direction of Trade Statistics: Yearbook, 1990.

2 GDP at market prices. Shares for 1962 are derived from data in International Financial Statistics (IFS), Supplement on Output Statistics, Supplement Series No. 8 (1984). Shares for 1988 are based on 1980 GDP levels in U.S. dollars, from the same source, and 1981–88 growth rates of GDP at constant prices, from IFS Yearbook, 1990.

3 Based on the sum of exports plus imports. Shares for 1962 are derived from data in IFS, Supplement on Trade Statistics, Supplement Series No. 15 (1988). Shares for 1990 are derived from the 1991 World Economic Outlook data base.

Relative Inflation Performance

Developments over the past several decades have strengthened the case for emphasizing price stability among the objectives of macroeconomic policy—not because high employment and growth are less important goals (indeed, many would argue they are much more fundamental)—but rather because it is difficult to sustain these objectives in the face of poor inflation performance.

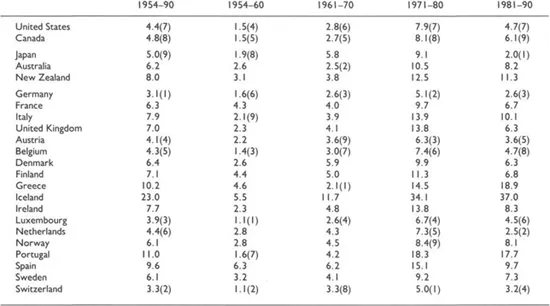

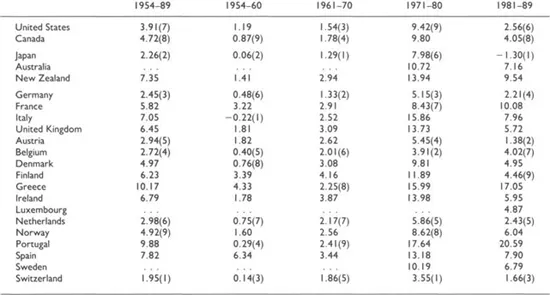

Tables 2 and 3 summarize the inflation experience of the past two decades in the industrial countries. The three largest countries have been among the leaders in holding down inflation. The tables show that Germany’s inflation record—on the basis of either consumer prices or wholesale prices—has been one of the three or four best during each of the past three decades. Japan has established strong credibility with the best overall record on each of the inflation measures during the 1980s and the second lowest rate of wholesale price inflation for the entire 1954–89 period. For the United States, monetary policy credibility was eroded considerably during the 1970s and rebuilt when the Federal Reserve acted forcefully to bring down inflation sharply during the early 1980s.3

Table 2. Consumer Price Inflation Rates Among Industrial Countries, 1954–901

(In percent, with rank order in parentheses)

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook data base.

1 Average annual rates.

Table 3. Wholesale Price Inflation Rates Among Industrial Countries, 1954–891

(In percent, with rank order in parentheses)

Source: International Monetary Fund, International Financial Statistics.

1 Average annual rates.

The credibility that Germany has earned in providing a nominal anchor has played a central role in the evolution toward economic and monetary union in Europe. Since the European Monetary System (EMS) started operating in March 1979, there have been strong trends toward lower average price and labor cost inflation, as well as higher inflation convergence, among the EMS countries participating in the exchange rate mechanism (ERM).4

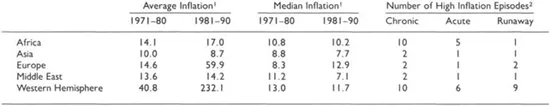

The difficulties of holding down inflation have been much more apparent among developing than among industrial countries. As shown in Table 4, the average rates of consumer price inflation for the five major developing country regions ranged from 10 percent to 41 percent during the 1970s and from 9 percent to 232 percent during the 1980s, while median inflation rates ranged from 8 percent to 13 percent during the 1970s and from 7 percent to 13 percent during the 1980s. During the two decades combined, there were 26 episodes of chronic inflation at annual rates of 20–80 percent for five or more consecutive years, 14 episodes of acute inflation at annual rates over 80 percent for two or more consecutive years, and 14 episodes of runaway inflation at annual rates over 200 percent for one year or longer.

Table 4. Consumer Price Inflation Among Developing Countries, by Region, 1971–90

1 Annual changes, in percent, from World Economic Outlook data bank. Average inflation rates represent arithmetic averages over each decade of weighted geometric averages for each year, where weights are proportionate to the U.S. dollar values of GDP over the preceding three years.

2 Based on individual country experiences reported in World Economic Outlook, May 1990, Table 13. Chronic inflation implies annual rates of 20–80 percent for five or more consecutive years. Acute inflation implies annual rates over 80 percent for two or more consecutive years. Runaway inflation implies annual rates over 200 percent for one year or more.

The wide dispersion of inflation experiences among individual countries suggests that countries may also differ widely in their incentives to rely on exchange rate commitments as a means of anchoring domestic prices. Focusing narrowly on anti-inflation benefits alone, the three largest industrial countries apparently have relatively little to gain from sacrificing monetary policy autonomy to undertake fixed exchange rate commitments. Needless to say, the pursuit of anti-inflation benefits is not the only reason for moving toward greater regional integration with fixed exchange rates.

Even for countries with relatively high inflation rates, the anti-inflation benefits associated with credible fix...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Part I Mechanisms for Promoting Global Monetary Stability

- I. Introduction

- II. Developments in World Economy and Implications for the International Monetary System

- III. Problems with Present System

- IV. What Can Be Done?

- References

- Tables

- Part II Issues in the Operation of Monetary Unions and Common Currency Areas

- Footnotes