eBook - ePub

Financial Sector Reforms and Exchange Arrangements in Eastern Europe

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Financial Sector Reforms and Exchange Arrangements in Eastern Europe

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

NONE

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Financial Sector Reforms and Exchange Arrangements in Eastern Europe by Guillermo Calvo, Eduardo Borensztein, Paul Masson, and Manmohan Kumar in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUNDYear

1993ISBN

9781557752796

Part I Financial Markets and Intermediation

I Introduction

This paper analyzes a number of issues related to the development of financial markets in the previously centrally planned economies (PCPEs) of Eastern Europe.1 These economies have embarked on major structural reforms to replace central planning with market mechanisms, both in the allocation of factors of production and in the production and distribution of goods and services. In most cases, they are implementing these reforms together with stabilization policies to deal with severe macroeconomic disequilibria. It is widely acknowledged that the success of the stabilization policies and the structural reforms depends in an important way on the development of efficient financial intermediaries and of credit and capital markets more generally.

The main issues concerning the development of financial markets revolve around the likely efficiency of these markets in mobilizing savings and in channeling them optimally, so as to facilitate the massive restructuring of the productive sectors that is essential for any sustained improvement in productivity and economic growth. At the same time, these markets play a critical role in facilitating transactions and in providing instruments for the conduct of monetary, fiscal, and exchange rate policies. Indeed, the implementation and efficacy of these policies depend on the efficiency of the financial markets; the role of these markets in monitoring, evaluating, and improving managerial performance can also be very important.

Although the scope and pace of financial sector reforms differ significantly among the PCPEs, they share certain characteristics, including the legacy of central planning, with severe distortions and dislocation in the financial and productive sectors; the lack of adequate financial and skilled manpower resources to develop the financial sector, as well as a lack of competition in it; the inadequacy or lack of auditing systems to provide information on the creditworthiness of prospective borrowers; underdeveloped and slow processes for settling transactions other than in cash; and the poor quality of bank portfolios and inadequate capitalization.

The paper is organized as follows: Section II provides an overview of recent developments and the role the financial sector can play, while Section III examines the development of the banking sector and contrasts the prereform system with the emerging system. Section IV focuses on some of the key weaknesses in the banking sector, including the poor quality of bank loan portfolios, inadequate capitalization, uncertain prospects of enterprises, and limited competition. Section V discusses the factors that influence the development of securities markets, in particular, the equity markets, and the role that such markets can play in privatization. Section VI discusses the conduct of monetary, fiscal, and exchange rate policies and how the emerging financial sector can affect their implementation. Section VII discusses the steps that need to be taken to establish the credibility of the new financial institutions, in particular, confidence in the banking sector, and to encourage optimal risk taking. Section VIII summarizes the major issues raised in the paper.

II Recent Developments and the Role of the Financial Sector

This section notes recent economic developments in the Eastern European countries, in particular, the sharp declines in output and real earnings. Among the reasons for the declines were the inevitable consequences of capital stock obsolescence and inefficiencies under the planned regimes, but problems in the financial sector, which led to an inadequate provision of credit to the enterprise sector, may also have been important.

Recent Economic Developments

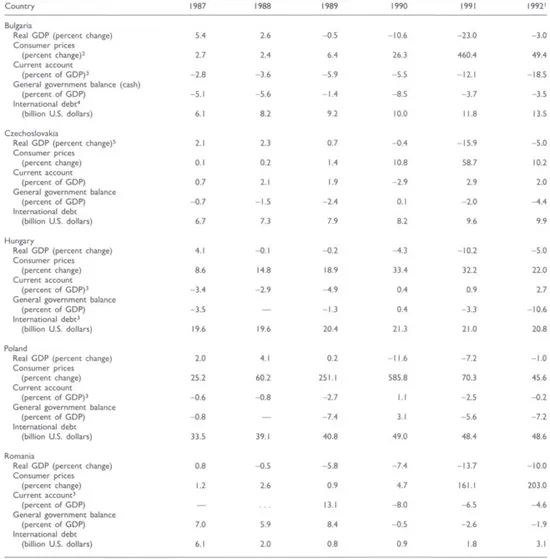

In 1990, real GDP declined by over 10 percent in Bulgaria and Poland, and by 4 percent and 7 percent, respectively, in Hungary and Romania (see Table 1). In all countries except Poland, the declines in output were even more pronounced in 1991 but appear to be less marked in some countries during 1992. It has been suggested that the measured output decline may overstate the actual decline owing to an increase in private sector output that is not fully measured because of index number problems resulting from rapid price changes.2 Nevertheless, the decline in output, particularly in industrial sectors, has been substantial and greater than anticipated.

Table 1 Eastern Europe: Recent Economic Developments

Sources: IMF, recent economic development reports, and staff estimates.

1 Preliminary estimates.

2 Average retail prices.

3 In convertible currencies.

4 End of year.

5 Real net material product through 1989.

In broad terms, the output decline may be regarded partly as an inevitable consequence of capital stock obsolescence and inefficiencies under the planned regimes and partly as the result of more specific phenomena, including the collapse of the old command linkages between enterprises, which have not yet been fully replaced by the market system; the disintegration of the old incentive system; the collapse of the trading arrangements within the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA) and changes in the terms of trade;3 and the pursuit of requisite stabilization policies. In some countries, the provision of real credit may have been squeezed owing, in part, to bigger price level jumps than anticipated and, in part, to structural problems in the financial sector.4 Indeed, these problems, and the associated capital market failures, may have contributed to the collapse of CMEA trade.

Stabilization policies were necessary to deal with the price surges that occurred in all of these countries, particularly in Bulgaria, Poland, and Romania, where liberalization followed long periods when prices had generally remained fixed and had played virtually no allocative role.5 Monetary overhang in several of the countries, combined with large budget deficits, further exacerbated inflationary pressures.

In implementing stabilization programs, several countries combined a planned contraction in money and credit in real terms with efforts to restrain real wages, with significant currency depreciations and fiscal adjustment. These policies succeeded to some extent in moderating inflation and reducing public sector deficits. The decline in deficits may appear puzzling given the decline in output, but the explanation lies in the artificial, sharp increase in enterprise profits that followed price liberalization, when enterprises’ inventories (including raw materials and intermediate goods) continued to be valued at their historic cost. The resultant increase in profits, illusory though it was, nevertheless had the effect of inflating corporate tax revenues. The current account position of some of these countries improved significantly as well, reflecting a sharp decline in domestic demand and, in Poland in 1990 and Hungary in 1990–91, strong export growth. Although these economies seem to be stabilizing, there has been concern that, together with the decline in output, the volatility in some key economic variables, including domestic prices, real earnings, interest rates, and growth and velocity of money, has exacerbated uncertainty about the structural changes that will be required to complete these countries’ transition to market economies. As the discussion below emphasizes, both of these developments may be, in part, related to the misallocation of credit through the existing financial intermediaries.

Role of the Financial Sector

In a market economy, the financial sector mobilizes savings and allocates them among competing ends, facilitates transactions, and prices and allocates risk. It is also instrumental in the pursuit of stabilization policies and in structural transformation.6 Rapid development and efficient functioning of the financial sector in the transforming economies is therefore crucial. Without active money and credit markets, appropriate monetary policy instruments will be lacking, and, in any case, the transmission mechanisms will be unreliable, making policies less effective.

The issue in the PCPEs has not been simply to liberalize a repressed financial system but rather to reform basic institutions and to design, create, and develop a market-oriented system. They are undertaking this task in an environment where, despite some recent major achievements in price and trade liberalization, several of the basic institutions of a market economy are still lacking. The legal structure relating to property rights and a broadly based private productive sector are in the early stages of development; a market economy ethos is still not fully in place.

The capital stock in all the PCPEs is partially obsolete and generally inefficient. Although, in the past, most of these countries had relatively high saving and investment rates, savings were often channeled toward unproductive and inefficient investments. The financial sector must be able to mobilize savings (both domestic and foreign) and to channel them into domestic investment that is profitable at world market prices if these countries are to attain sustained economic growth.

Financial repression, especially in conjunction with high and unstable inflation, can severely impede growth. It is manifested in a number of ways; for example, savings instruments are underdeveloped, and the real return on savings is negative, leading to low saving rates and to the channeling of savings into unproductive activities. At the same time, asset holders seek protection by holding foreign currency-denominated assets or, if possible, by shifting their assets abroad. Because of the uncertainties generated by inflation, enterprises do not undertake sufficient investment. There is, however, growing evidence to suggest that too rapid financial liberalization under conditions of macroeconomic instability and inadequate bank supervision can lead to high and volatile real interest rates, which can exacerbate financial instability and be detrimental to productive investment (Sundararajan and Baliño, 1991). The evidence emphasizes that the underlying problems—related to a narrow tax base and large budgetary deficits (as well as sharp income inequalities)—that influence the governments’ ability to undertake rapid policy adjustments should be tackled at the same time as financial liberalization (Dornbusch and Reynoso, 1989).

There is a consensus that financial liberalization can improve resource allocation; however, there is less agreement as to whether or not it can substantially increase the saving rate (Borensztein and Montiel, 1991). To the extent that financial liberalization in the PCPEs reduces liquidity constraints on households, the precautionary motive for saving might be weakened. In addition, the development of consumer credit markets might increase the indebtedness of the household sector, again leading to a temporary fall in savings. However, the availability of a greater range of savings instruments, with positive real returns, is likely to stimulate overall saving. Furthermore, the increase in uncertainty engendered by the transition, with regard to employment opportunities and the future of social safety nets, may, in fact, lead to greater precautionary saving.

III Development of the Financial Sector

This section describes the prereform financial system in the ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Part I Financial Markets and Intermediation

- Part II Exchange Arrangements of Previously Centrally Planned Economies

- Footnotes