eBook - ePub

Recent Experiences with Surges in Capital Inflows

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Recent Experiences with Surges in Capital Inflows

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

NONE

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Recent Experiences with Surges in Capital Inflows by Robert Kahn, Adam Bennett, María Carkovic S., and Susan Schadler in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUNDYear

1993ISBN

9781557753502

Sterilization

Sterilization was the first line of defense against the surge in inflows, regardless of its cause, in each of the countries. Sterilizing was attractive because it could be implemented quickly and bought time to consider the likely causes and persistence of inflows and to formulate a longer-term response. It sought to curb the monetary effect of the inflows and tended to lock in a cushion of reserves against a possible reversal. As inflows persisted most governments eased the degree of sterilization.

Narrowly defined, sterilization is the exchange of bonds rather than money for foreign exchange. In fact, open-market operations were only one of the mechanisms that central banks employed to limit the influence of capital inflows on money. Increases in reserve requirements on all or selected parts of bank deposits, often designed to lengthen the maturity structure of deposits and discourage foreign inflows to the banking system, were also important. Other sterilization-type policies included various forms of central bank borrowing from commercial banks; the shifting of government deposits from commercial banks to the central bank; raising interest rates on central bank assets and liabilities; curtailing access to rediscount facilities; and, in Spain, direct credit controls. Sterilization was also accomplished through sales of government liabilities: this was important in Egypt, where the Government sold bonds to reduce money creation from deficit financing. To capture the bulk of these mechanisms, a broad measure of sterilization is required—namely, changes in the domestic assets of the central bank net of liabilities to the public sector and banks—that is, the domestic counterpart of currency issue.

Another difficulty in identifying sterilization is determining causality—whether the reduction in net domestic assets caused subsequent capital inflows or offset previous inflows. In fact, for most of the countries both lines of causality were undoubtedly at play. Except in extreme circumstances—when interest rates are invariant to the supply of bonds or to banks’ free reserves, or inflows are insensitive to interest rate differentials—sterilization will, at least to some degree, increase inflows. Nevertheless, estimates, reported in Appendix I, of the offset coefficient, that is, the degree to which sterilization induces offsetting capital inflows, suggest that, at least historically, the countries under review, with the possible exception of Thailand, had scope for effective sterilization. It must be remembered, however, that for all of these countries domestic financial markets have become increasingly integrated with foreign markets and estimates of offset coefficients using historical data probably underestimate the mobility of capital.

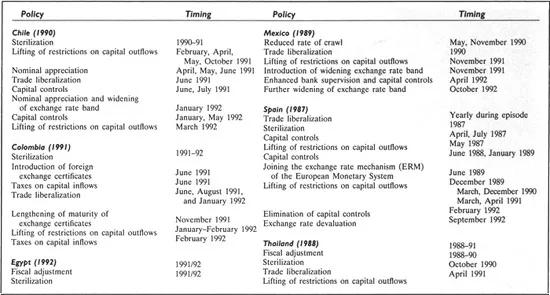

Box 1. Timing and Sequencing of Policy Responses to Capital Inflows1

Source: IMF staff reports.

1 First year of episode noted in parentheses after country name.

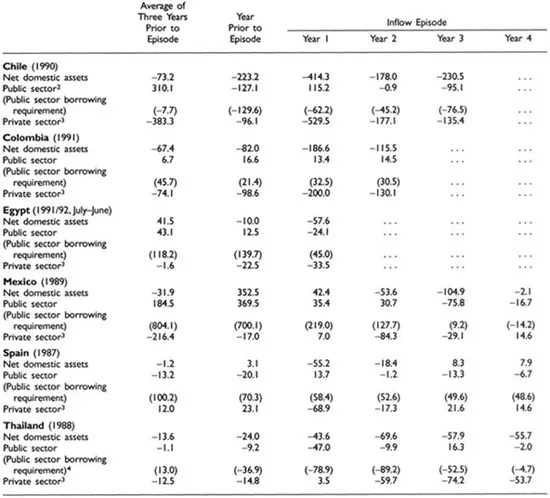

Ignoring questions of causality, sterilization—broadly defined as a deceleration or drop in the net domestic assets offsetting the monetary effects of capital inflows—occurred in each country in the first year of the capital inflow episode (Table 3). This deceleration reflected restraint in net credit to the private sector, except in Mexico and Thailand. After the first year, the decline in net domestic assets slackened in most countries owing partly to lower growth in reserves, but also reduced reliance on sterilization. The exceptions were Mexico and Thailand, where restraint of credit to the private sector strengthened (although only moderately) in the second year of the inflow. Sterilization occurred on the largest scale in Chile and Colombia—countries where the initial tightening of credit probably also played a large role in attracting the increase in inflows. In these countries, sterilization took the form of increases in reserve requirements and open market operations. In Colombia, about one year into the inflow episode, the central bank shifted to heavy reliance on the sale of foreign exchange certificates—forward foreign exchange assets bearing a market interest rate in exchange for current foreign exchange receipts.

Table 3. Net Domestic Assets of the Central Banks1

(Percent contribution to increase in currency)

Source: IMF staff reports and estimates.

1 Domestic assets of the central bank net of liabilities to the government and commercial banks. First year of episode noted in parentheses after country name.

2 Public sector assets in Chile are calculated net of medium- and long-term foreign liabilities of the central bank, most of which were acquired in the context of 1983–85 rescheduling agreements with foreign commercial banks.

3 Including the banking sector.

4 Fiscal accounts (fiscal year October–September) converted to calendar-year basis.

Countries reduced their reliance on aggressive sterilization for several reasons. First, it carried large quasi-fiscal costs. These were most clear when sterilization took the form of open market operations. Then, the net cost to the central bank per bond issued was the difference between the interest on domestic bonds and the return on foreign reserves—interest earned, for example on U.S. Treasury bills, plus the actual depreciation of domestic currency. This difference was largely a reflection of the domestic risk premium and ranged in 1990–91 from virtually zero in Thailand to over 10 percent in Chile, Colombia, and Spain. For Colombia—where bond sales were greatest among the countries reviewed—the direct quasi-fiscal cost in 1991 is estimated at 0.8 percent of GDP. Such calculations establish the lower limit of actual costs. A broader measure would also capture the effect of higher domestic interest rates on the government’s debt-service payments. The costs of other forms of sterilization are varied. For example, an increase in unremunerated reserve requirements would be profitable for the central bank.

Second, aggressive sterilization through open market operations risked intensifying the conditions that attracted large inflows: by augmenting the supply of bonds, it put upward pressure on domestic interest rates, sustaining an important attraction to additional inflows. Again the experience of Colombia is instructive. A marked reduction in sterilization in mid-1992 resulted in a large drop in short-term interest rates, a slackening of the inflows, and a deceleration of the monetary aggregates.

Third, by forcing foreign inflows into purchases of government bonds and sustaining high domestic interest rates, sterilization deprived the economy of the benefits of capital inflows—higher domestic investment and growth. This consideration carried particular weight in Thailand as the durability of the inflows and their contribution to investment and growth became clear.

Exchange Rate Policy

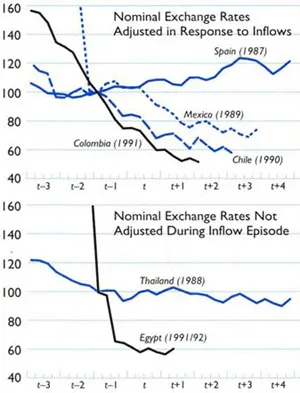

At the outset of the surge in inflows, each of the countries, except Spain, maintained a fixed, or broadly fixed, rule for the exchange rate. Initially, the authorities in each country took the position that the sustainable real exchange rate over the medium term was not significantly higher than its level prior to the surge in inflows. However, unchecked, inflows fed demand for nontraded goods, pushing up prices and the real exchange rate. Thus, whether inflationary pressures should be pre-empted through a nominal appreciation became a policy issue.

Four countries, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Spain, resorted to nominal appreciation or a modification in the announced path for the exchange rate (Chart 4 and Box 2). Each of these countries, except Mexico, had initially responded to the surge in inflows with relatively aggressive sterilization. When it became apparent that this could not be done on a scale sufficient to reduce money growth and inflation to targeted levels, exchange rate policy was adjusted, often in conjunction with the imposition of capital controls.

Chart 4. Nominal Exchange Rate Indices1

(Index of SDR per unit of national currency; period t—1 = 100)

Source: Information Notice System.

1 Period t is the first year of the surge in capital inflows, the timing of which is indicated in parentheses after country name.

Box 2. Exchange Rate Policy Changes During Episodes1

Chile (1990)

- At the outset of the inflow episode, the government’s exchange rate rule was to adjust the reference rate for the peso against the U.S. dollar by the difference between domestic and U.S. inflation. The peso was allowed to fluctuate within a band around the reference rate. In response to the capital inflows, the Government undertook a series of small revaluations.

- April 1991: Revalued reference exchange rate 0.7 percent.

- May 1991: Revalued reference exchange rate 0.7 percent.

- June 1991: Revalued reference exchange rate 2 percent.

- January 1992: Revalued the reference exchange rate by 5 percent and widened the band around the reference rate within which the market rate is allowed to fluctuate to 10 percent in either direction (previously 5 percent). Within a short time, the peso moved to the top of the band. Thus, January 1992 measures led to a nominal appreciation of about 10 percent.

Colombia (1991)

- June 1991: Nominal revaluation of 2.6 percent in foreign currency terms. Previously, foreign exchange operations were conducted at an official exchange rate that crawled against the U.S. dollar. Also, a system was introduced to exchange foreign exchange receipts for non-interest-bearing exchange certificates denominated in U.S. dollars with a 90-day maturity issued by Banco de la Republica. At maturity, the certificates are exchanged for domestic currency at a “reference” exchange rate set by Banco de la Republica. The certificates are redeemable before maturity at a discount. The market price of foreign exchange certificates became the exchange rate.

- November 1991: The maturity of the certificates was extended to one year. This amounted to another nominal revaluation of 1.9 percent in foreign currency terms.

Mexico (1989)

- 1990: Preannounced depreciation of peso against U.S. dollar reduced from around 15 percent a year (1.3 percent a month) to 10 percent a year (May) and 5 percent a year (November).

- November 1991: Reduced preannounced depreciation of the peso against U.S. dollar from annual rate of 5 percent to 2½ percent a year and simultaneously created and gradually widened the band within which the peso could fluctuate. The aim was to move gradually toward a margin of about 4 percentage points between the maximum and minimum points of the band.

- October 1992: Increased the rate of depreciation of the maximum point of the exchange rate band so as to widen the band by some 9 percentage points by the end of 1993.

Spain (1987)

- June 1989: Entry into the exchange rate mechanism (ERM) of the European Monetary System.

- September 1992: Devaluation of the peseta by 5 percent from the reference rate within the ERM.

- November 1992: Devaluation of the peseta by 6 percent from the reference rate within the ERM.

Source: IMF staff reports.

1 First year of episode noted in parentheses af...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- I. Introduction

- II. Overview

- III. Causes of Surges in Capital Inflows

- IV. Policy Responses

- V. Effects of the Inflows

- VI. Conclusions

- Appendix I. Capital Mobility: The Empirical Evidence

- Appendix II. Statistical Tables

- Bibliography

- Box 1 Timing and Sequencing of Policy Responses to Capital Inflows

- Box 5 Data Sources and Transformations

- Tables

- Footnotes