This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Sovereign Assets and Liabilities Management

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

NONE

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Sovereign Assets and Liabilities Management by INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUNDYear

2000ISBN

9781557756947

1 Introduction

The papers contained in this volume were presented at a conference entitled “Sovereign Assets and Liabilities Management” hosted by the International Monetary Fund and the Hong Kong Monetary Authority in Hong Kong SAR in November 1996. The conference focused on a wide range of issues confronting policymakers in managing their sovereign assets and liabilities in a world of mobile capital flows and integrated capital markets. The papers draw on the experiences of policymakers and private sector participants that have been actively involved in formulating and implementing debt and reserves policy. The policy choices are discussed against the background of alternative theoretical frameworks that are presented by a number of academics.

In the first paper, Cassard and Folkerts-Landau focus on the design of an institutional framework that enables a sound risk management of sovereign assets and liabilities and that reduces the vulnerability of sovereign portfolios to the volatility of international capital markets. The paper recommends the assignment of sovereign debt management to a separate debt agency with a large degree of autonomy from political influence. In particular, the authors propose that the sovereign authority communicate its debt strategy and policy constraints to the debt agency in the form of a benchmark portfolio, specifying the currency composition, maturity structure, and permissible instruments of the portfolio. An analytical framework that can be used to derive a benchmark and test its robustness is then discussed. The paper stresses that public disclosure of the reserve portfolio and benchmark as well as the performance of portfolio managers are key to achieving sound reserve management practices.

In the second paper, Dooley advocates a conservative debt management strategy, arguing that governments should limit their issuance of debt to homogeneous long-term domestic currency instruments. His argument is based on the premise that the main consideration in structuring sovereign asset and liability management is to avoid default. The issuance of only a single class of debt is necessary to avoid an adverse selection problem for sovereign credits, while denominating public debt in domestic currency is needed to obviate the large changes in the foreign currency value of government revenues owing to changes in the real exchange rate. The other reason for shunning foreign currency debt is the governments’ limited ability to generate foreign currency revenues.

In his comments on the paper, Jorion outlines alternative theoretical models of asset and liability management to that proposed by Dooley, each of which implies a different conclusion regarding debt management policy. For instance, he argues that governments should issue long-term domestic debt when real shocks are important, but when monetary shocks dominate, such strategy would not be optimal. In alternative situations, if the government’s anti-inflation stance is not credible, the private sector may increase the price of debt if it expects the government to inflate its debt away. In these circumstances, issuing floating rate debt or foreign currency debt may be preferable from the sovereign’s viewpoint.

Following on Dooley’s paper, de Fontenay and Jorion provide a comprehensive survey of various approaches to sovereign debt management, focusing on the optimal size of foreign currency debt for a country (if any) and the optimal composition of sovereign debt. In contrast to Dooley, the authors reach the conclusion that the sole issuance of domestic currency debt is not necessarily the optimal strategy for the sovereign. Indeed, developing countries should diversify the currency composition of their external debt to reduce the risks associated with the impact of interest rate and exchange rate changes on their ability to meet their external debt obligations. They also argue that the issuance of foreign currency-denominated debt can give the government’s anti-inflation program credibility as it provides a signal that the authorities will not attempt to reduce the value of their debt through inflation. Taking Australia as a case study, the authors demonstrate how modern portfolio theory can be applied to generate an optimal currency composition for the Australian portfolio that is consistent with the authorities’ objectives as well as projections of market developments.

In his comments on the paper, Makoff points to the sensitivity of the results of the analytical framework chosen to the choice of inputs, that is, historical or projected risk/return parameters. He suggests that caution should be exercised in applying portfolio theory; that the conclusions should be tested under a wide range of assumptions; and that significant constraints should be imposed to guarantee sufficient diversification and to enforce consistency with other portfolio objectives.

The second part of the conference volume focuses on the experience of various countries in managing their sovereign assets and liabilities. Sullivan opens the discussion, outlining both the institutional approach to debt management in Ireland and the main objectives and constraints facing policymakers. In Ireland, the National Treasury Management Agency was established in 1990 in response to a rapidly growing and increasingly complex debt position. According to Sullivan, the National Treasury Management Agency’s principal objectives are to manage the debt in such a way as to protect both short-term and longer-term liquidity; contain the level and volatility of annual fiscal debt-service costs; reduce the Exchequer’s exposure to risk; and outperform a benchmark or shadow portfolio. To achieve the desired fixed/floating mix and the targeted maturity structure of its foreign currency liability portfolio, the National Treasury Management Agency uses actively derivative markets. In view of Ireland’s debt dynamics and the decline in domestic interest rates over the past few years, the National Treasury Management Agency has reduced the foreign currency component of its sovereign debt, issuing primarily longer-term fixed rate domestic currency debt.

Rådstam highlights the approach of the Swedish National Debt Office to debt management. The Swedish National Debt Office’s objective is to minimize the long-term cost of the foreign currency debt within the risk limits established by the Board of the Swedish National Debt Office. With a foreign currency debt portfolio of over $60 billion, the Swedish National Debt Office is one of the largest borrowers in international markets. The currency composition of the benchmark has been chosen to reflect the prevailing currency regime in Sweden. In terms of the fixed/floating split, half of the debt is at floating rates and the other half at fixed rates with maturities of one, three, five, seven, and ten years in equal proportions. While the aim of the Swedish National Debt Office’s benchmark is to ensure an average outcome in terms of cost, the agency is allowed to take currency and interest rate positions relative to the benchmark within risk limits laid down by the board. Indeed, during the past five years, the active management of the foreign currency debt has resulted in savings of over SKr 11 billion.

Wheeler then examines New Zealand’s experience and ongoing innovation with sovereign debt management. The New Zealand Debt Management Office’s objective is “to identify a low risk portfolio of net liabilities consistent with the Government’s aversion to risk… and to transact in an efficient manner to achieve and maintain that portfolio.” Wheeler outlines ways in which New Zealand’s implementation of debt policy has been upgraded over the years. In particular, he notes that New Zealand has reconfigured its debt portfolio to remove foreign currency exposures and achieve a longer duration of NZ-dollar debt, including inflation-indexed securities.

Against the background of trends in Belgian public indebtedness and the reform of Belgian capital markets in the early 1990s, de Montpellier discusses the development of the Belgian Treasury’s methodology of establishing a debt portfolio structure. Such a structure is defined as one that best minimizes the financial cost of the public debt within acceptable risk levels, while taking account of the macroeconomic objectives of the policymaker (budgetary and monetary policies). Indeed, in addition to the financial risks (market risk, credit risk, and operational risk) that any market participant is subject to, the manager of public debt has to be aware of the “macroeconomic” risks facing the policymaker. De Montpellier argues in favor of managing public debt separately from foreign assets, as the cash flows on the asset side of the state’s balance sheet are not as sensitive to financial variables as are those on the debt side.

The papers presented by both Nugée and Rigaudy review trends in central bank reserve management in recent years. Based on an adherence to the balance sheet approach, Nugée argues in favor of managing sovereign assets and liabilities jointly, even if this entails identifying a common objective that does not interfere with the separate objectives of the central bank and the Ministry of Finance. He argues that from a national perspective, risks inherent in holding foreign currency reserves are best managed when aggregated at the highest level possible. If risks are too disaggregated, then control is sacrificed and the accumulation of a large number of small risks can become an unacceptable large risk. Nugée points out that by focusing on net reserves or liabilities, the sovereign can direct its attention more effectively to the part of its balance sheet at risk.

Rigaudy also identifies a number of significant changes that have taken place with regard to the objectives and investment policies of central banks. He notes that although the size of foreign reserves has increased substantially, the currency composition of reserves has remained stable. He argues that despite a large literature on the optimal level of reserves, the size of reserves in most countries is a consequence of economic policy, particularly monetary policy, rather than an objective per se. However, while liquidity remains the central issue for foreign exchange management, return maximization has become a more important concern. Rigaudy also discusses a number of thorny issues in reserve management, such as the management of gold reserves, the increased mobility of capital, and the difficulties of managing market activities in public institutions.

The next two papers present a practical experience of Australia’s and Denmark’s reserve management approaches. Battellino describes Australia’s reserve management process, highlighting that reserves are primarily held to fund foreign exchange intervention with the purpose of moderating movements in the exchange rate in times of volatility. To this end, the Australian benchmark includes the three major reserve currencies (the U.S. dollar, the deutsche mark, and the Japanese yen) in roughly equal proportions, as the yen and deutsche mark display a strong negative covariance with the Australian dollar, while the latter is closely linked to the U.S. dollar. Battellino notes that the central bank has chosen a benchmark duration of 30 months because once the duration moves out beyond two and a half years, the risks of negative returns increase substantially. While the investment committee of the central bank is given considerable discretion in managing the reserve portfolio, the performance of the portfolio is carefully monitored: the portfolio is marked to market daily and reported to the Governors quarterly and to the public annually.

In contrast to Australia, Hansen explains that the Kingdom of Denmark manages its foreign debt and foreign exchange reserves within a coordinated framework focusing on the net foreign debt. The net debt is managed via the setting of a benchmark portfolio consisting of assets or liabilities in U.S. dollars, ERM currencies, Japanese yen, sterling, and Swiss francs, the distribution of which is decided by the Ministry of Finance and the central bank on a quarterly basis. Interest rate risk is managed by ensuring that the sovereign foreign assets and liabilities have a short duration, so that neither the interest rate risk of the government or central bank nor the combined risk of the two institutions is affected significantly by government borrowing to finance currency intervention.

Pilato exposes the risks that arise when lower-credit sovereign borrowers swap out of debt issued in foreign currencies back in their domestic currency to eliminate market risk and take advantage of arbitrage opportunities. He argues that the use of swaps constrain the borrowing capacity of lower-credit sovereigns by utilizing their credit lines with banks and expose them to higher counterparty risk as they often have to deal with lower-credit swap counterparties. Pilato describes an approach to measure the “cost” of swap counterparty credit risk based on the most likely or expected exposure and funding spreads. To consider this issue, he derives a debt optimization framework that takes into account borrowing capacity risk in addition to the conventional measures of risk—cost and volatility of cost. The optimal solution derived by the model is shown to be different from that derived by the usual optimization framework.

The last part of the conference volume turns to a discussion of private sector experiences with sovereign asset and liability management. Klaffky, Glenister, and Otterman discuss risk management and its application to central banks. After identifying several types of risk—market risk, credit risk, liquidity risk, legal risk, and operations risk—that confront central bankers, the paper describes the quantification of portfolio market risk and the role of a benchmark in the investment strategy. The authors especially focus on how risk should be managed in an institutional setting, discussing the types of checks and balances that should be established to facilitate the monitoring and improvement of the risk management process.

In the final paper of the volume, Hakanoglu discusses the methodology used in the Goldman Sachs Asset-Liability Management Model to determine the optimal maturity profile and currency composition of a sovereign debt portfolio. Hakanoglu first highlights the simulations (Monte Carlo) used to construct an optimal portfolio, then discusses the various issues involved in measuring the risk tolerance of the client, and finally demonstrates the construction of an optimal portfolio to reflect such risk tolerance. The paper explains how a benchmark portfolio can be derived and stresses that a benchmark should represent a minimum risk position for the sovereign that takes into account various market exposures and the long-term objectives and constraints under which the sovereign is operating. Typically, a benchmark would approximate the desired long-term portfolio of the sovereign, and would be used to measure the performance of the actual sovereign portfolio.

2 Management of Sovereign Assets and Liabilities

Many emerging market countries have gained greater access to external sources of finance in recent years, and this in turn has increased their exposure to volatility in international asset prices. Indeed, developing country sovereign entities are often especially exposed to international disturbances, because of their large stock of foreign currency liabilities (relative to national income) and the relatively risky structure of their debt portfolios (by currency composition and maturity profile). What this means in practice, in a sometimes volatile international financial environment, is that the benefits of prudent macroeconomic management and structural reforms are all too often severely compromised by unexpected changes in foreign interest rates and exchange rates.

Major multinational firms (both financial and nonfinancial) have adapted to the volatility of financial markets through the use of hedging techniques and derivative instruments to manage their risk exposures. This approach has been facilitated by important advances in financial technology in the past decade, and by specialized risk management techniques developed by institutional fund managers. In contrast, many sovereign entities—some of them major players in international financial markets with large financial assets and liabilities—have mostly lagged behind the private sector in this respect. The recent experience of a small, but growing, number of countries that have reformed the management of sovereign assets and liabilities demonstrates that sound risk management can lessen the impact of external financial developments on national wealth, and potentially increase returns on foreign reserves and reduce borrowing costs.

The current literature on risk management is rich in its treatment of portfolio allocation problems, but it provides little guidance for sovereigns on how to manage the risk exposure of their assets and liabilities. By drawing on the experience and the well-established methodologies of large institutional investors and pension funds, and on the experience of sovereigns that have reformed their debt management policies, this chapter examines (1) the risks involved for a government in carrying a large open foreign currency exposure; (2) the design of institutional arrangements that provide appropriate incentive structures for debt and reserves management; and (3) the establishment of benchmark portfolios embodying the preferences of the policymaker for incurring currency, interest rate, and credit risks, as well as reflecting the macroeconomic and institutional constraints of the country. These issues raise thorny questions about the optimal currency exposure of a sovereign; the extent of interaction between debt management policy, reserves management, and monetary policy; the degree of independence of debt management from political oversight; and the extent to which reserves management should be under public scrutiny. Although this chapter primarily targets emerging market economies and small industrial countries, which are more vulnerable to swings in foreign currencies and interest rates, the framework discussed is applicable to most countries.

Foreign Currency Exposure of Sovereign Liabilities

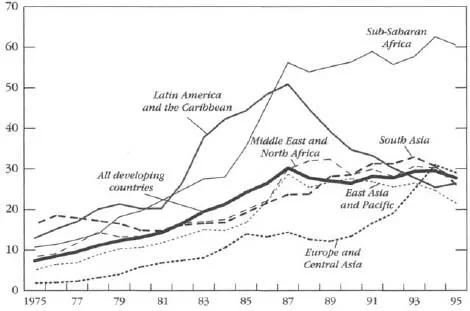

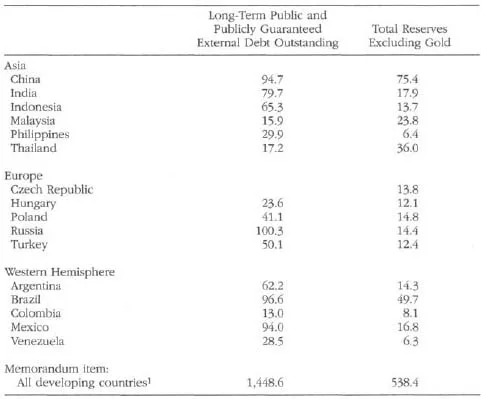

The external exposure of developing countries’ sovereign liabilities has increased steadily during the past two decades, from 7 percent of GDP in 1975 to about 30 percent of GDP in the mid-1990s (Figure 2.1). In 1995, the external debt held or guaranteed by developing country sovereigns was almost three times larger than their foreign currency reserves, exposing governments to a large net currency risk exposure (Table 2.1). External debt also exposed developing countries to foreign interest rate risk. Indeed, about half of developing countries’ external debt in 1995 was exposed to foreign interest rate risk, as 20 percent of the external debt was short term (under a one-year maturity), and 40 percent of the remaining long-term debt was at floating rates (mostly indexed to LIBOR—the London Interbank Offered Rate).

Figure 2.1. External Long-Term Public and Publicly Guaranteed Debt Outstanding

(In percent of GNP)

Source: World Bank, Global Development Finance database.

Note: The groupings are as shown in the source.

Table 2.1. Long-Term Public and Publicly Guaranteed External Debt Outstanding and Reserves Excluding Gold in Selected Developing Countries, 1995

(In billions of U.S. dollars)

Sources: International Monetary Fund, International Financial Statistics (June 1997); and World Bank, Global Development Finance, 1997.

1 World Bank data. International reserves include ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents Page

- Acknowledgments

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Management of Sovereign Assets and Liabilities

- 3. Debt and Asset Management and Financial Crises: Sellers Beware

- 4. Foreign Currency Liabilities in Debt Management

- 5. Sovereign Liability Management: An Irish Perspective

- 6. Management of Risks in Foreign Currency Funding and Debt Management

- 7. Autonomous Sovereign Debt Management Experience

- 8. Public Debt Management Strategy: Belgium’s Experience

- 9. Central Bank Reserves Management

- 10. Trends in Central Bank Reserves Management

- 11. Reserves Management Operations in Australia

- 12. Foreign Borrowing by the Kingdom of Denmark

- 13. Credit Costs and Borrowing Capacity in Debt Optimization

- 14. Risk Management Process for Central Banks

- 15. Technical and Quantitative Aspects of Risk Management

- Footnotes