eBook - ePub

Public-Private Partnerships, Government Guarantees, and Fiscal Risk

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Public-Private Partnerships, Government Guarantees, and Fiscal Risk

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

NONE

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Public-Private Partnerships, Government Guarantees, and Fiscal Risk by M. Cangiano, Barry Anderson, Max Alier, Murray Petrie, and Richard Hemming in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUNDYear

2006ISBN

9781589064935

Chapter 1 Public-Private Partnerships

There is no clear agreement on what does and what does not constitute a PPP. A PPP has been defined as “the transfer to the private sector of investment projects that traditionally have been executed or financed by the public sector” (European Commission, 2003, p. 96). But in addition to private execution and financing of public investment, PPPs have two other important characteristics: first, there is an emphasis on service provision and investment by the private sector; and, second, significant risk is transferred from the government to the private sector. Some or all of these four features also characterize other means by which the role of government in the economy has been reduced over the last 20 years—including privatization, joint ventures, franchising, and contracting out.1 However, PPPs are distinct in that they represent cooperation between the government and the private sector to build new infrastructure assets and to provide related services. In fact, two methods that have been used specifically to reduce the role of government in the economy in favor of the private sector—concessions and operating leases—are in the first case a form of PPP and in the second case can be structured like a PPP.

A. Basic Features of PPPs

A typical PPP takes the form of a design-build-finance-operate (DBFO) scheme. Under such a scheme, the government specifies the services it wants the private sector to deliver, and then the private partner designs and builds an asset specifically for that purpose, finances its construction, and subsequently operates the asset (i.e., provides the services deriving from it). This contrasts with traditional public investment projects, under which the government contracts with the private sector to build an asset but provides the design and financing itself and, in most cases, then operates the asset once it is built. The difference between these two approaches reflects a belief that giving the private sector responsibility for designing, building, financing, and operating an asset leads to increased efficiency in service delivery. More specifically, such “bundling” is believed to provide an incentive for the private sector to design and build assets with features that enhance the quality or lower the costs of service provision over the long term.

The government is, in many cases, the main purchaser of services provided under a PPP. These services can be purchased either 1) for the government’s own use (a prison), 2) as an input to provide another service (a school), or 3) on behalf of final consumers (a free-access road). Private operators also sell services directly to the public, as with a toll road or railway. Such arrangements are often referred to as concessions, and the private operator of a concession (the concessionaire) pays the government a concession fee and/or a share of profits. Typically, the private operator owns the PPP asset while operating it under a DBFO scheme, and the asset is transferred to the government at the end of the operating contract, usually for less than its true residual value (and often at zero or a small, nominal cost). In this case, a PPP is often referred to as a build-operate-transfer (BOT) or build-own-operate-transfer (BOOT) scheme.

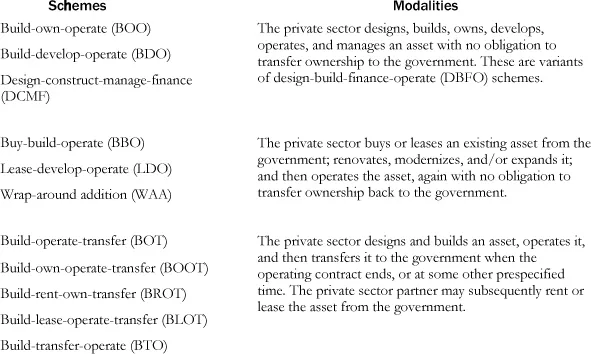

The term PPP is sometimes used to describe a wider range of arrangements. In particular, some PPPs exclude functions that characterize DBFO schemes. Most common in this respect are schemes that combine traditional public investment and private sector operation of a government-owned asset (note that the builder and the operator of the asset are not the same). This arrangement sometimes takes the form of an operating lease, although it can be considered a PPP if the private operator has responsibility for asset maintenance and improvement.2 Private sector involvement in asset building alone—which can take the form of a design-build-finance-transfer (DBFT) scheme or a financial lease—is not, strictly speaking, a PPP because it does not involve service provision by the private sector. This paper does not seek to explicitly exclude any type of arrangement from the definition of a PPP, and refers to cases in which the public sector partner is a public enterprise rather than the government.3 However, it pays most attention to PPPs that involve both investment and service delivery by the private sector, as well as private financing and ownership. Hence the focus is on DBFO schemes.4 Box 1 describes some of the many variants of PPP schemes.

Box 1. PPP Schemes and Modalities

Uses for PPPs

PPPs appear to be particularly well-suited to providing economic infrastructure. This is primarily for three reasons. First, sound projects that address clear bottlenecks in roads, railways, ports, power, and other infrastructure are likely to have high economic rates of return and therefore to be attractive to the private sector. Second, in economic infrastructure projects, the private sector can be made responsible not only for constructing the infrastructure asset but also for providing the principal services related to it, allowing them to tailor asset design specifically to this purpose. Third, to the extent that these services are supplied directly to final users, charging is both feasible and, from an efficiency standpoint, desirable.

Social infrastructure is somewhat different in these regards. Although many social investment projects are clearly worthwhile, the private sector is not usually the principal supplier of social services. Thus, while PPPs may be formed to build and maintain public schools and hospitals, the government tends to continue to be the provider of the education and health care services deriving from them. Moreover, charging for government-supplied social services is not commonplace. Hence, social infrastructure PPPs offer smaller potential efficiency gains than either economic infrastructure PPPs or schemes that combine public investment and subsequent contracting out of the operation and maintenance of schools, hospitals, and other social infrastructure.5 That said, there are many examples of successful PPPs in social sectors.

Financing

The private sector can raise financing for PPP investment in a variety of ways. When services are sold to the public, the private sector can go to the market using the projected income stream from a concession (e.g., toll revenue) as collateral. Where the government is the main purchaser of services, collateral can comprise shadow tolls paid by the government (i.e., payments related to the demand for services) or service payments by the government under operating contracts (which are based on continuity of service supply, rather than on service demand). The government may also make a direct contribution to project costs. This can take the form of equity (where there is profit sharing), a loan, or a subsidy (where social returns justify a project). The government also can guarantee private sector borrowing.

PPP financing is often provided via special purpose vehicles (SPVs). An SPV can be a consortium of companies responsible for all aspects of a PPP, and as such it can be a means of exploiting the advantages from bundling. In practice though SPVs are often a group of banks and other financial institutions that combine and coordinate the use of their capital and financial expertise. Insofar as this is their purpose, an SPV can facilitate a well-functioning PPP.6 However, an SPV can also serve as a veil behind which the government controls a PPP either via the direct involvement of public financial institutions, an explicit government guarantee of borrowing by an SPV, or a presumption that the government stands behind it. Where this is the case, the risk is that the SPV will be used to shift debt off the government balance sheet. Private sector accounting standards require that an SPV be consolidated with an entity that controls it; by the same token, an SPV that is controlled by the government should be consolidated with the latter, and its operations should be reflected in the fiscal accounts.7, 8

Where the government has a claim on future project revenue, it can contribute to the financing of a PPP by securitizing that claim. With a typical securitization operation, the government sells a financial asset—its claim on future project revenue—to an SPV. The SPV then sells securities backed by this asset to private investors and uses the proceeds to pay the government, which in turn uses them to finance the PPP. Interest and amortization are paid by the SPV to investors from the government’s share of project revenue. Because the investors’ claim is against the SPV, government involvement in the PPP appears limited. However, the government is in effect financing the PPP, although this fact can be masked by the recording of sale proceeds received from the SPV as revenue.9

B. Country Experience

A number of advanced OECD member countries now have well-established PPP programs. Undoubtedly the best developed of these is the United Kingdom’s Private Finance Initiative (PFI), which began in 1992. The PFI is currently responsible for about 14 percent of public investment, with projects in most key infrastructure areas. Other countries with significant PPP programs include Australia (and in particular the state of Victoria) and Ireland, while the United States has considerable experience with leasing.10 Many Western European countries now have PPP projects, including Finland, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain, although their share in total public investment is quite small.11 Reflecting a need for infrastructure investment on a large scale and weak fiscal positions, a number of countries in Central and Eastern Europe have embarked on PPPs, including Croatia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland.12 There are also fledgling PPP programs in Canada and Japan. PPPs in most of these countries are dominated by road projects. In addition, greater use of PPP–type arrangements has been proposed to develop a trans-European road network (European Council, 2003).

In the rest of the world, PPPs have made fewer inroads. In Latin America, however, Chile, Colombia, and Mexico have used PPPs to promote private sector participation in public investment projects. Chile has a well-established PPP program that has been used mainly for the development of roads, airports, prisons, and irrigation. In Colombia, PPPs have been used since the early 1990s, but early projects were not well-designed. A relaunched PPP program emphasizes road projects. In Mexico, PPPs were first used, though unsuccessfully, in the 1980s to finance roads. Since the mid-1990s, Mexico has used PPPs with greater success for public investment projects in the energy sector through the PIDIREGAS scheme, and they are beginning to be extended to the provision of other services.13 Some other Latin American countries, most notably Brazil, are planning significant use of PPPs. There has also been some discussion of a regional approach to infrastructure development that would involve PPP—type arrangements.14

PPPs are beginning to take off in Korea, the Philippines, and Singapore (and, as noted above, also in Japan), but progress elsewhere in Asia is limited, despite strong interest in PPPs in some other countries, including India, Indonesia, and Thailand. In Africa, South Africa, a clear regional leader, has embarked upon or is developing PPPs in a number of sectors. Few other African countries have much experience with PPPs, although Mozambique has embarked on concessions to rehabilitate rail terminals and a port, while other countries have tried alternative forms of private sector involvement in infrastructure, especially in the water and power sectors (e.g., in Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal). Appendix 1 outlines the experience with PPPs in Chile, Ireland, South Africa, and the United Kingdom. Selected experiences of other countries are included elsewhere in the paper.

Although a number of countries have developed PPP programs, it is too early to draw meaningful lessons from their experiences. The U.K. government published a comprehensive assessment of the PFI (H.M. Treasury, 2003), which was informed in part by the results of independent studies and was favorable in terms of both the program’s procedures and its outcomes. Overall, however, while particular aspects of country experiences support some of the conclusions in this paper, few general lessons can be drawn yet, especially from the experiences of emerging market economies and developing countries.

C. Economic Principles

PPPs themselves have not been subject to extensive economic analysis. However, there is a good deal of analytical work that can be brought to bear on the issues raised by PPPs.15

Ownership and Contracting

The standard arguments for and against government ownership are relevant to PPPs. As a general rule, private ownership is to be preferred where competitive market prices can be established. Under such circumstances, the private sector is driven by competition in the product market to sell goods and services of a quality and price that is acceptable to consumers and by the discipline of the capital market to make profits. Various market failures (natural monopoly, externalities) can justify government ownership, although the result can be that government failure simply substitutes for market f...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acronyms and Abbreviations

- Preface

- Introduction

- I. Public-Private Partnerships

- II. Government Guarantees and Fiscal Risk

- III. PPPs, Guarantees, and Debt Sustainability

- IV. Summary and Conclusions

- Appendixes

- References

- Boxes

- Footnotes