![]()

1 Territorial change in post-authoritarian Indonesia

Averting collapse

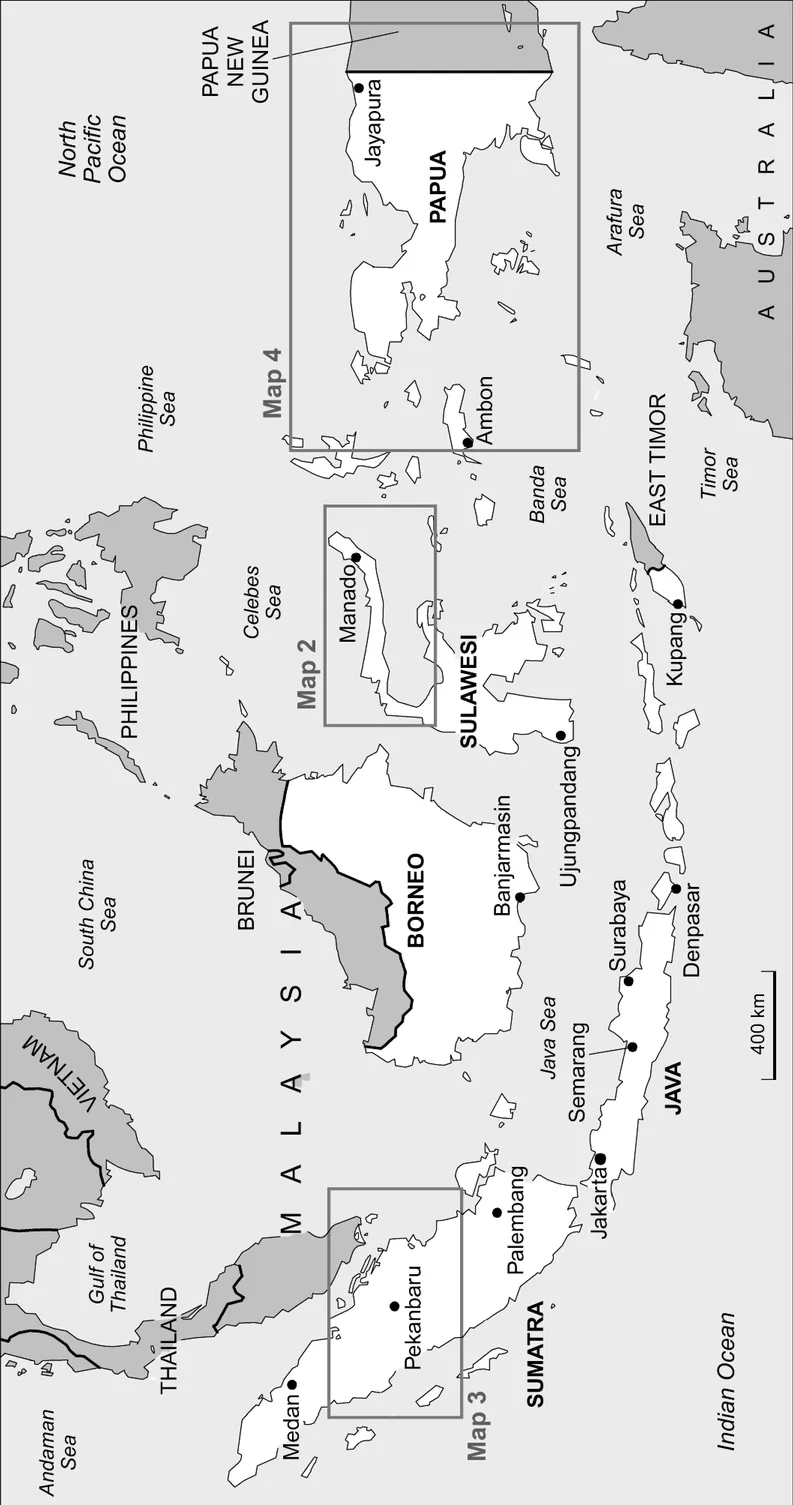

Amid Indonesia’s economic and political upheaval in the late 1990s also loomed the specter of its territorial collapse. The Soviet Union and Yugoslavia had each splintered earlier in the decade and observers at the time raised the prospect of Indonesia’s “balkanization” (Bolton 1999; Hadar 2000). Experts and pundits alike cautioned that transition and political reform could weaken the state, embolden the regions, and lead to a domino effect beginning with the breakaway of East Timor followed by a general fragmentation of the archipelago into a dozen or so states.

As things turned out, Indonesia survived and has since remained largely intact. East Timor gained independence in 1999, but along with West Papua, it had not been part of the Indonesian nation-state at independence in 1950, and was forcibly incorporated in 1975. Dominoes did not fall and the archipelago did not splinter the way many had feared. In fact, the state has territorially been quite resilient in recent years.

Indonesia’s political transition did spur on a territorial shuffle of another less expected kind. Instead of external fragmentation and collapse, Indonesia experienced an internal fission where provinces and districts were divided into ever smaller units resulting in an unprecedented proliferation of new subnational territories. The number of provinces has grown from 27 to 33 and the number of districts from 292 to around 450. These internal territorial changes have attracted much less attention than the challenges of Timor, Aceh, and West Papua but they affect many more people and suggest a need for a different way to think about territorial politics in Indonesia and elsewhere.

People living in areas with newly-drawn local boundaries experience an immediate change in patterns of everyday life. Their leaders suddenly change because new districts or provinces come with new mayors, district chiefs, or governors. Rules change for a range of issues from tax codes and local budget allocations to public service provisions. And the fragmentation affects the physical aspects of everyday life. Where you go to perform even the most mundane tasks such as registering your car or filing for a marriage license may suddenly change because of new boundaries.

Politically, local territorial changes affect election outcomes. Locally, it can form a function similar to gerrymandering where constituencies might be divided or split off altogether leading to a changing political calculus of candidates running for office. Incumbents might be threatened in such new schemes but it also offers opportunities for new players who can fill the ranks of executive, legislative, and bureaucratic offices that accompany new regions. Even before new provinces or districts are approved, prospective candidates may see the virtue of campaigning for potentially new seats.

In a richly diverse and multi-ethnic country such as Indonesia, there is also an important cultural aspect to local territorial politics. Imagine how one area splitting off from another could shift majority—nority relations in both regions. In a new district or province, a former Muslim minority could find itself the new majority. Alternatively, those formerly in the majority could find themselves suddenly the minority. From the national state perspective, territorial change may be useful to split up groups seeking to mobilize against the state along lines of identity. In other instances, it may serve to compartmentalize different groups into discrete ethnic units, such as the ethno-federal system of the Soviet Union (Brubaker 1996).

The local territorial changes that occurred in Indonesia then raise some compelling theoretical questions. What explains the sudden onset of territorial change in states? Why do some states fragment externally while others seem to fragment internally? And what can this phenomenon tell us more broadly about political change and territoriality? This book addresses these questions and argues that local territorial change is not a mild or incremental form of secession occurring throughout the archipelago. Instead, it needs to be seen in the context of an increasingly fragmented and competitive political system.

This means that analyses of territorial politics needs to go beyond the older frames of center—periphery upon which scholars have long relied. In Indonesia, theories of center and periphery took on particular salience between Java and the so-called “Outer Islands.” The questions about territorial politics then were inevitably framed around this division. Did Java over-extract from the resource wealthy and less densely populated Outer Islands? Did a process of Javanization impose a cultural and political model outside of Java? How can political representation be balanced between the two regions? In short, most discussions of Indonesia’s territorial politics began and ended with this split which came to represent other dichotomies such as modern vs. traditional, richer vs. poorer, import-dependent vs. export-dependent and so on.

More recently, East Timor, Aceh, and West Papua attracted the bulk of international attention when it came to thinking about territorial politics during the New Order. The spotlight shone on issues of human rights, economic development, and self-determination. These regions were seeking to break away from the Indonesian nation-state and while their motivations were many, their vision of territorial independence was uniform. Even after the fall of Suharto, the interpretations of ethnic and religious conflict throughout the archipelago often came to be framed as residues of the old state fighting emergent challengers. These kinds of analyses also seeped into questions about Indonesia’s territorial survival in the late 1990s. The narrative of a highly centralized, militarized, and “Javanized” core suggested that many in the periphery wanted out.

In fact I argue just the opposite. Territorial change in post-Suharto Indonesia is characterized by profound centripetal tendencies where local and national groups are coming together to form what I call territorial coalitions. These coalitions which consist of an array of groups at the local, regional, and national levels can also be seen in other countries. In many places, national politics is bound together with local demands in a way that sees territorial change as a preferred political outcome. The Indonesian case clearly shows how this happens, but the phenomenon is more general.

Territory and mobilization amidst political change

The internal fragmentation occurring in Indonesia is puzzling because borders are institutions that have rules governing their own behavior which become self-perpetuating and resistant to change. In other words, we expect boundaries to be sticky (Newman 2006: 102). Although political boundaries are often contested and resisted, when they do change, they merit explanation as to why and how that occurs (Shapiro 1996).

The official narrative in Indonesia, articulated by countless bureaucrats, local executives, and policy advisors, is that the creation of new administrative regions improves economic and democratic efficiency. The mantra repeated almost word-for-word by proponents for new districts or provinces is that it would “bring government closer to the people and the people closer to the government.”1

Theoretically, efficiency arguments are rooted in economic approaches that assume the role of government is to minimize negative externalities and provide positive ones. States are relied upon to provide public goods such as accessible education systems, transportation infrastructure, public libraries, public transportation, and so on, which would otherwise be under-supplied. Often, these kinds of goods can be delivered more efficiently if they are administered by smaller, more localized units. Thus, an increase in the number of local administrative units should match some optimally efficient territorial size with which to deliver a particular set of goods.2 Territorial change can thus be explained by the increasingly complex and specialized provision of goods and services (Sack 1986).

But one problem with this functionalist explanation is that it cannot explain the timing and variation of territorial change. If this were a purely efficiency oriented phenomenon, the increases in new provinces should be steadier and not cluster around a particular time period. Similarly, there is no clear pattern of territorial change based on even the most cursory of administrative efficiency indicators. For example, we might expect that larger, more populous, or demographically-dispersed provinces would split but no such patterns emerge in a broad comparison (see Appendix for more details). In other words, efficiency explanations assume a rational state that administers affairs to maximize local utility, a perspective that ignores politics. In fact bureaucratic and efficiency explanations are often invoked in order to obscure politics and confer legitimacy on a process that is otherwise dubious (Ferguson 1994).

A second problem with this explanation is that it approaches territory with a kind of cold materialism that assumes regions and territories are ripe and ready to be divided and administered as states see fit. In fact, much of the literature on regionalism and decentralization tends to assume the essential existence of territories as enclosed spaces that can be empowered or weakened depending on state policy. But we know that this is not the case. As Paasi notes, territories are not “frozen frameworks where social life occurs. Rather, they are made, given meanings, and destroyed in social and individual action” (Paasi 2003: 110).

To that end, this study makes three arguments about territorial organization, reorganization, and change. First and most immediately, territorial change often results from new or shifting political institutions. If we talk about territories being made through “social and individual action,” the political institutions and changes within them help shape and direct what those actions will be. Institutional reforms change the “rules of the game” in a way that territory at the regional and local level become highly desirable. In Indonesia, the reforms of democratization and decentralization that emerged in the wake of Indonesia’s political transition are identified as the key changes that spurred and shaped the process of territorial change. While this book focuses on recent changes, early chapters of the book explore how changes in the institutions of colonial rule and their particular political, economic, and cultural context led to shifting definitions and organizations of territorial administrative units in the archipelago. Furthermore, institutional change has also driven territorial change in other countries as well.

Second, territorial change of the kind seen in Indonesia needs to be understood in the context of both competition as well as mutual gain. These are highly politicized and contentious processes, but we should not assume that new administrative territories emerge simply because local regions demand them and the national state gives in. Local demands exist, but change emerges in the context of what I call “territorial coalitions,” coalitions that span different levels of territorial administration and create linkages between different levels. Instead of taking center and periphery as unitary actors this study argues that each level is fragmented with multiple actors. In turn, their interests are shaped by various economic, political, identity, and security related motivations. In this way, the arguments presented here challenge the prevailing binary of center and periphery.

Finally, the book argues that coalitions are possible at certain historical junctures because territories have a conceptual plasticity to them. Instead of taking the notion of territory and debating or assuming some exclusive material or ideological essence, territory needs to be recognized for its inherent flexibility. People imbue territory with different meanings and understandings, and for this reason, it can take on a kind of multi-dimensional nature. The different ways that individuals and groups think about and see value in territory can lead to conflict. But in many ways it can also lead to the basis for cooperation in the form of the territorial coalitions mentioned above. In other words, the flexibility or plasticity of territory is what allows for interests to overlap and coalitions to occur. In this sense, territory is a kind of focal point that allows groups to coordinate and mobilize for territorial change.

In Indonesia, decentralization and democratization offered a number of different ways to think about territory. Local groups saw new opportunity to create a new region of their own either at the district or the provincial level. A people living in a northern Sulawesi region called Gorontalo, as we will see later, saw an opportunity to become their own Muslim majority province and break away from a Christian dominated province. At the same time, territory had a different meaning for national legislators who saw opportunities for electoral and patronage gains. Territory had profoundly different benefits for each of these groups, but still provided an underlying basis of cooperation which was necessary for the new territory to be approved. The overlapping interests between local groups and national growth then laid the foundation for a political coalition that pushed for and achieved the creation of a new province.

These alignments, or coalitions, are striking in the context of Indonesian politics where the conventional wisdom dictates that social groups tend to avoid broad coalitions. The common interpretation of Indonesia’s political transition in 1998 and 1999 attributes success to social movements despite the inability to work together (Aspinall 2005; Weiss 2006). This study suggests that where aims have been narrower and more concrete, there have emerged alliances that cut across levels of administration as well as categories of groups that do not typically work together.

Instead of focusing exclusively on national level politics or local level demands I show how national, regional, and local levels are linked through webs of networks and alliances. It is these territorial coalitions that help us understand the redrawing of boundaries, the emergence of new provinces, and the changing patterns of regional politics in Indonesia and elsewhere. This study thus explores the linkages between groups and actors in both the center and in the peripheral regions and how that can lay the groundwork for territorial change.

Methods and approach

The study of territorial change and territorial coalitions as framed above requires various approaches looking at politics at different territorial levels. This book takes a broad historical approach at the national level to understand the relationship between political institutions and territorial change. At the same time, local-level politics and histories are also a critical part of the story and this requires digging around in far-flung regions where national media are often absent.

The first chapters in the book focus on the national-level political institutions during colonial, post-colonial, and contemporary times to examine patterns of territorial change. During each period, shifts in territorial administration emerge due to the overlapping interests of national-level actors and local societal actors. During the colonial period, this was manifested in the tension between the state imperative for homogeneity versus its recognition of immense social and political diversity throughout the archipelago. In the post-colonial era and especially during the authoritarian New Order period, a similar dynamic can be framed in the context of state—society relations. Finally, in the contemporary reformasi era, I show how national and local actors collaborate to form coalitions to produce a shifting terrain of new provinces and districts.

The historical chapters are based on secondary and some primary materials. In many ways, they tread familiar ground for those knowledgeable in Indonesia’s history, but it seeks to do so in a way that sheds light on how events formed and shaped the territorial institutions of the Indonesian state. In this way, they seek to de-naturalize territorial administration as simply technocratic or efficiency based and instead highlight the deeply politicized nature of territorial administration.

The second section of the book consists of three in-depth case studies aimed to better assess the mechanisms and processes taking place on the ground. National institutional change trickled down to local levels and affected politics in contrasting ways. In Gorontalo, territory came to be framed as “marginality in the periphery” where local groups mobilized around grievances with the ethnic majority in the region. In Archipelagic Riau (Kepri) province, debates for a new province centered around membership and what it meant to be an orang Kepri in post-Suharto Indonesia. Finally, I examine how the politics of national security takes on a ...