![]()

Part I

Context

![]()

1 The organization of champagne

A historical and structural

introduction

Steve Charters

Introduction: champagne the wine

Champagne is a product which is rooted in its place and in history. The business of champagne cannot be understood without some knowledge of where it comes from and how the past has shaped the way the industry is structured, managed and perceived by those who run it – and these factors form the core of this chapter. As a preliminary, however, it is necessary to remember that champagne is a wine, and certain things are distinctive about wines. Most significant in this context is the fact that wine cuts across primary, secondary and – at times – tertiary industries (Carlsen & Charters, 2006). It is primary as it is based on an agricultural resource – the grapes. It is secondary because there is production involved (the process of manufacturing wine from grape juice). It is often tertiary when there is a service element attached to it, most clearly with wine tourism. This produces clear management challenges which do not apply to most other industries; the skills required to grow quality wine grapes, make good wine and provide a great experience for the public are not necessarily the same.

Wine is also self-evidently alcoholic, a fact which makes it attractive to many consumers and provides a level of marketing advantage but which also brings with it attendant management difficulties centred on issues of health and abuse concerns. Further, champagne is also by definition an effervescent wine. This is significant physiologically, as it is well-established that carbon dioxide accelerates the uptake of alcohol in the blood stream, thus speeding its euphoric effect. It is, thus, no coincidence that sparkling wines and specifically champagne have become the wine of celebration, as they make drinkers feel relaxed and cheerful more rapidly than other wines.

Finally, it should be noted that champagne is locally a very significant industry. The Champagne-Ardenne region of France is seeing a greater population decline than any other. In that context any industry which employs around 30,000 people and is worth 4.5 billion euros is important. In turn, as will be seen in Chapter 4, this has an impact on land values and it also acts as one of the major attractions for tourists, contributing yet more to the local economy as well as to social life and stability in a very rural area.

The geography and history of champagne

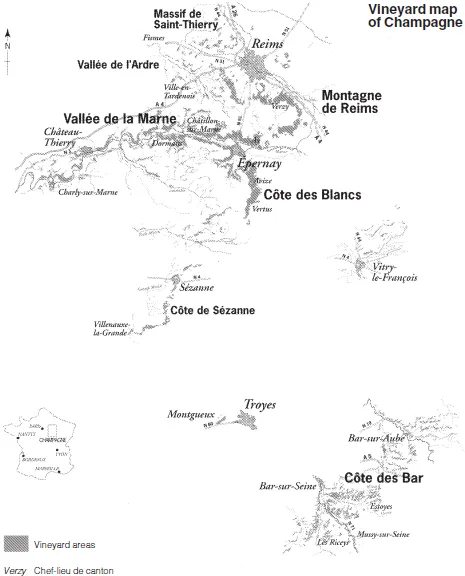

Champagne is produced in the north of France, in a region centred on Reims and Epernay, about 130 kilometres east-north-east of Paris (the geography of the region is shown in the map at Figure 1.1). This is a cool wine-producing region – as far north as grapes for high-quality wines are grown in France. The region divides into a number of sub-regions (between four and six, depending on which system one follows) and up to 20 sub-sub-regions (Anon., 2010b). The key sub-regions are: the Montagne de Reims, which curves around the south and west of its eponymous city (including sub-regions such as the Massif de St Thierry); the Marne valley, which stretches westward from Epernay to within 70 kilometres of Paris; the Côte des Blancs, southwards from Epernay, and including the region around the town of Sézanne; and the Côte des Bar (the Aube), separated from the previous three regions and about 100 kilometres south of Epernay.

Three hundred and nineteen villages currently possess the right to have vineyard land within their area. There are just over 34,000 hectares of land available to plant within the appellation d'origine contrôlée (AOC) area, and 34,051 are now planted – meaning that the entire demarcated area is effectively in use. Additionally there are almost 275,000 individual plots of viticultural land each averaging less than 1,250 square metres; land use and ownership is thus highly dispersed. Almost all of the wine-producing villages are in the Champagne-Ardenne region of France. Most of these villages (72 per cent of vineyard land) are in the departement1 of the Marne, with a further 21 per cent of vineyard to the south in the Aube.

Wine has been produced in this region for over 1,500 years (Unwin, 1996),2 but sparkling wine has only been made for around 350 years, and until the end of the nineteenth century most production was still wine (Guy, 2003). The mythology of the region claims that the effervescent wine was invented by the monk, Dom Pérignon (Kladstrup & Kladstrup, 2005), who was responsible for the provisions of the Abbey of Hautvillers, just outside Epernay. However, the truth is likely to be much more prosaic than that. Three random factors coincided to create the conditions for sparkling wine. The first was a ‘mini ice age’ which dominated Europe from the late medieval period until the nineteenth century, reducing average temperatures. In cold autumns this temperature change slowed down the fermentation of wine, often stopping yeast activity temporarily before it restarted in the late spring of the following year (Phillips, 2000). The other two factors were technological: the development of harder glass in England, making bottles a convenient and strong container for the first time, and the realization that cork could be an effective and airtight closure for those bottles (Phillips, 2000). Until the time these two developments occurred, if fermentation was arrested and then recommenced any carbon dioxide created by yeast activity dissipated into the air from the casks in which the fermenting grape juice (known as the must) was contained. Once the must, not fully fermented, was placed in a corked bottle, when fermentation recommenced in the spring following a cold winter the gas was trapped in the bottle, making an effervescent wine.

Figure 1.1 Map of Champagne. (Source: CIVC)

The first evidence of sparkling wine being made from champagne in fact records its production in England, by adding sugar to still wine, and dates from at least 1662, some years before the period that Dom Pérignon was managing the cellars at Hautvillers (Stevenson, 1998). Nevertheless, it was evidently being produced in the region by the end of the seventeenth century, albeit in small quantities (Brennan, 1997). However, these styles of wine were not what we would recognize as champagne. Initially they were only mildly sparkling and were cloudy (because each bottle still contained many millions of yeast cells). The history of much of the following three centuries was one of refining the process by which the wine was made (something outside the scope of this introduction, but which is explained in detail by Kladstrup & Kladstrup, 2005). Additional information on the development of production and its human context can be found at the beginning of Chapter 12.

As in most of France, growing grapes in the Champagne region was part of local agriculture and thus carried out by many small agricultural producers, who often practised polyculture and might have a very small vineyard area. However, improving the production of sparkling wine was costly, as was the effort required to distribute the product in the markets of Paris and (later) London, St Petersburg, Berlin and New York. The capital and knowledge needed to do this meant that – for sparkling wine at least – production became the domain of merchants (négociants) who had the time and money to invest in it. These merchants, known also as the maisons (houses), owned little land, but purchased grapes from the small-scale growers (termed vignerons in French). From the mid-eighteenth century, when the maisons became more and more important, there was substantial hostility between them and the growers, much of which was focused on the issue of grape price; the vignerons naturally wishing to be paid as much as possible, the houses seeking to minimize that payment. Around this a host of other factors, such as the creation of the legally recognized identity of ‘Champagne’ as a wine-producing region, added other sources of conflict (for an excellent examination of this see Guy, 2003).

Even for the négociants, however, sparkling wine was initially less attractive than still wine. It was costly and time-consuming to make, whereas still wine could be sold more rapidly. However, in the eighteenth century, as transport systems began to improve throughout France, there was growing competition for the still wines of Champagne in the major market of Paris, particularly as increasing numbers of wines from Burgundy, often more full-bodied, were being sold there (Brennan, 1997). This competition threatened the viability of traditional still wines from the region, and so merchants began to increase the amount of sparkling wine they produced, by way of differentiation (Brennan, 1997). The fact that in the bottle a wine could last longer without spoiling allowed for greater potential in export markets also, for lengthy transport in casks was potentially damaging to the wine.

The sustained export efforts of the houses, especially during and after the Napoleonic period, meant that champagne became one of the few internationally recognized wines. National consumption was modest during the nineteenth century, rising from just over two million bottles a year in the 1840s to less than three million forty years later. Conversely, exports went from five million to 18 million between 1840 and 1880. As a result of this international reputation champagne (and the houses which made it) faced problems with fraud as others tried to trade in on its reputation. Consequently, in 1882 the houses formed a grouping which became the Union des maisons de champagne (UMC) in an attempt to face the problem jointly. Meanwhile, in the face of a series of agricultural depressions and the devastation of the Champagne vineyards by phylloxera3 in the 1890s, the growers decided to pool their resources, forming several small unions. These in turn united in a federation in 1896 to develop more power in the face of the houses, becoming a single representative body, the Syndicat général de vignerons (SGV), in 1904.

The SGV opposed the UMC over a series of issues, including grape price, the delineated area of Champagne and issues relating to the ‘fraudulent’ production of champagne (Guy, 2003). Antagonism was such that there were riots in the region in 1911 (examined in more detail in Chapter 5). There was an irregular grape supply, causing difficulties for both sides of the champagne industry and a reduction in sales worldwide had caused a surplus of stock. However, the First World War showed both sides of the industry that they had more substantial enemies than each other, a perspective reinforced by the continuing agricultural depression in the 1920s and the more general economic decline of the 1930s, which resulted in a period of international protectionism. In order to counter this decline the two Unions created the Commission de propagande et de défense des vins de Champagne (committee for the promotion and defence of the wines of Champagne), designed to support their wine. Arguments about the price of grapes remained the key point of dispute between the groups, so out of this body the Commission de Châlons (named after the major local administrative city) was created in 1935, representing the two sides of the industry equally, and with the power to fix the grape price in a way that was fair to both growers and houses.4

As this process was cementing the relations between two opposing elements of champagne production, another was adding to their cohesion – the desire to delineate the boundaries of the area in which grapes could be grown and champagne produced. Again this was essentially to protect the houses against fraud from other wine producers and to protect the economic monopoly of the growers over grape production by excluding outsiders. Although this notion of a delimited area had been disputed in the nineteenth century (Guy, 2003), from 1911 onwards both sides came to realize the need for a coherent definition of the geography of production. As shown in more detail in Chapter 5, this development saw interregional disputes, even amongst the growers, as well as between growers and houses, but eventually this was finalized in 1927, and incorporated into the Appellation Contrôlée (AOC)5 system in 1936, with the boundaries established being essentially those which exist today. The grant of AOC status did not just determine the borders of the region for producing champagne – it also introduced rules designed to improve the quality (and thus the reputation) of the wine for the benefit of all. Thus viticultural techniques were prescribed. These included determining the grape varieties which could be planted (excluding the less high-quality ones which had been introduced in the wake of phylloxera) as well as pruning methods. It also set compulsory production techniques (harvesting, pressing, storage, etc.), again in an attempt to guarantee the quality of what was in the bottle and thus enhance the region's fame.

Effectively, what had been an antagonistic production environment developed into one which was more cooperative. This was formalized in 1941 when the Commission de Châlons became a permanent organization called the Comité interprofessionnel du vin de Champagne (CIVC), thus giving legal validity to inter-professional cooperation. The organization's executive committee was constituted with exactly the same number of growers and négociants and it was (and remains) jointly chaired by the presidents of the SGV and of the UMC. In 1946, the CIVC was given a role to organize, control and direct the production, transformation, distribution and the exchange of wine produced in Champagne, and it has quasi-governmental powers over aspects of the viticulture and wine production in the region, with the ability to set legally binding decrees over these issues. Since the early 1990s the CIVC has lost its power to set or even recommend a grape price at harvest as a result of European Union (EU) action to stimulate free markets in goods, but the other responsibilities it subsequently developed have been retained (see below).

The contemporary organization of the champagne industry

The producers of champagne

The crucial issue in the organization of champagne remains the balance between growers and houses. The growers own 90 per cent of the land bearing champagne grapes, but are responsible for selling less than one quarter of all bottles of wine. The houses make over two thirds of the sales but own less than ten per cent of the vineyard land. The two groups are thus interdependent, and the situation is made more complex by the existence of a number of growers’ cooperatives.

There are 20,000 Champenois (people who come from Champagne) who state that they own land on which champagne grapes can be grown. Of these, 15,200 are grape growers, meaning that almost 5,000 own land but have it managed by someone else. The average holding of vineyard land is 2.22 hectares – a small area but, with a potential gross income of €130,000 p.a., still financially viable. Of these growers around 4,800 sell champagne under their own label (they are known as récoltant-manipulants (RMs)) but they cannot effectively buy grapes or wine on the open market, so generally they are of a small size – and few of them are well-known outside the region; indeed most of their sales are made only in the region, at the cellar door. The growers sell abou...