![]()

Part I

Picturing Fashion/Fashionable Pictures

Risking It All at the Hippodrome de Longchamp

Heidi Brevik-Zender

Late-nineteenth-century Paris was the setting for myriad sites of fashionable display. Along its tree-lined boulevards, stylishly dressed bourgeois citizens paraded past trendsetting courtesans during afternoon promenades. At the Palais Garnier, the capital's gilded opera house, audience members' opulent garments often enjoyed more scrutiny than did the performances on stage. Sale days at Le Bon Marché, one of the city's lavish department stores, were occasions to exhibit the latest styles on one's body while purchasing them. Even visits to view cadavers at the city morgue—a popular if morbid tourist attraction of the period—were instances where smartly dressed dandies and “well-dressed women nonchalantly trailing silk dresses” (Zola 1970: 132)1 demonstrated their sartorial skills to crowds of onlookers drawn to a space where both corpses and clothes were on display.2 Yet, of the many events that drew a fashion-conscious crowd to particular venues of metropolitan Paris, few could rival in spectacle and importance the horse races of Longchamp.

At least once a year, the Hippodrome de Longchamp became Paris's most significant nexus of stylish display. Refurbished in 1857 under Baron Haussmann (1809–91) and lying just west of the city limits in the Bois de Boulogne park, the race track at Longchamp was, by the late nineteenth century, the most popular racecourse in France and an incomparable site of fashionable pageantry. The Grand Prix de Paris, held every spring starting in 1863, was a daylong affair that attracted thousands of spectators, as much for the chance to observe the well-dressed attendees and to witness the new clothing styles that inevitably made their debut as for the highstakes horse race.

Festivities commenced in the morning, when fashionable Parisians in carriages and on horseback processed down the Champs-Elysées toward the racetrack to the delight of observers seated on benches placed there by the city for the occasion (Herbert 152). Upon arrival at the sporting grounds, viewers arranged themselves according to a hierarchical schema that located the aristocracy, government officials, prominent social figures, and members of the exclusive Jockey Club in covered stands, while the bourgeoisie and lower classes sat in open carriages and on the grass around the track. Following the race, high society convened at gala balls where evening fashions were put on parade.

This chapter analyzes the ways in which the Longchamp racetrack served as a vital—if incidental—location of fashionable display in latenineteenth- century Paris. Drawing on paintings of the races by Edgar Degas (1834–1917) and Édouard Manet (1832–83), as well as on the serial novel Nana by naturalist writer Émile Zola (1840–1902), I examine artistic portrayals of the pageantry, physical arrangement, and metaphorical function of sartorial exhibition at Longchamp. How, according to these writers and artists, did fashionable display play a role in both reinforcing and weakening the hierarchies of a socially stratified society? How did differences of class inform the sartorial topography of the racecourse, and how was it represented? In addressing these questions, I focus in particular on the notions of danger and risk that were important elements of late-nineteenth-century fashion, horse racing, and modernity alike.

Risk-taking informed many of the leisure practices of the nineteenth century, an era that witnessed an increase in the popularity and incidence of gambling. For a rising bourgeois population with a growing expendable income, gambling represented a publicly sanctioned way in which thrills could be purchased for an ostensibly affordable price. “Gambling and its transformation of every social gathering and chance encounter into an arena of desire,” observes historian Thomas M. Kavanagh, “held the power to infuse the humdrum reality of everyday life with real excitement” (2000: 507).3 The sport of horse racing, which rapidly gained in popularity following its late-eighteenth-century debut in France, developed in tandem with betting. The pari, or wager, which could be placed with any of the racecourses' ubiquitous bookmakers, was one of the most compelling elements of this growing spectator sport. The connection between gambling and horse racing was cemented in 1863 with the advent of the Grand Prix de Paris, whose total purse of 100,000 francs made it the highest endowed race in the world. Often drawing crowds of over 100,000 people (Gaillard 88), the Grand Prix quickly became both a mecca for public gambling and a premiere event on the chic Parisian social scene (Jones 214).

Yet for all its thrilling popularity, gambling at the races could be extremely dangerous, for the financial risks incurred by patrons could have grave consequences. In Zola's novel Nana, the horse owner Vandeuvres loses his entire fortune at the Grand Prix, a loss that compels him to end his life in spectacular fashion by setting fire to his own stables and burning inside them. At once a celebration of the glamour and excitement of Longchamp and a cautionary tale about the vices it promotes, this episode of Nana serves as an extreme reminder of the very real risks incurred at the track.

Risk was also an important factor in nineteenth-century sartorial fashion. In public, much depended upon appearance, for what one wore could dictate who one was perceived to be, which was perhaps more important than who one actually was. Members of the lower and middle bourgeoisie who had aspirations of social ascendancy, like those already at the height of public standing, needed to obey the ever-changing edicts of fashion by donning the very latest in dresses, hats, jackets, jewels, and accessories. “Fashion has exercised in Paris, for several centuries, an absolute power,” wrote Madame Emmeline Raymond, editor of the long-running periodical La mode illustrée, in 1867 (923). Violations of this seemingly omnipotent, uncompromising Parisian fashion system were a danger to one's social standing and thus were to be avoided at all costs.

In bourgeois and high society alike, fashionable garments were necessary in order to manifest a wearer's fiscal worth. It was risky from a social standpoint to appear at important functions without the appropriately fine garments. Specific spaces, from the private salon to the public park and theater, each required its own specific brand of sartorial chic. In turn, the stylish outfits donned by smart Parisians helped to identify these milieus as particularly fashionable. Elegant attire in these settings, it was assumed, bore witness to a person's elevated social class and, in some cases, could serve as an entryway to an even higher public rank. Notes Thérèse Dolan, “costume was of great importance for those who wish[ed] to appear to have what they d[id] not possess, because that [wa]s the best way of getting it later on” (380). Clothes were thus indispensable tools for the aspirations of bourgeois social climbers. Some risked a great deal for fashion, a trend of which, not surprisingly, some nineteenth-century writers were highly critical. For example, in Pot Bouille, his cynical portrait of Third Empire bourgeois mores, Émile Zola portrayed the destruction of the Josserand family, whose ruinous obsession to clothe daughters of marriageable age in the latest fashions results in a father's premature death and the adulterous, unhappy union of its younger daughter.

Fashion was thus an area of risk for economic reasons as well as social: one needed to invest in articles of clothing in order to gain access to privileged spaces and attain or sometimes hold on to a preferred social standing, despite the fact that these desired results were far from guaranteed. Moreover, risk could also be incurred on a symbolic level, for the meaning of any given garment was constantly subject to dangerous slippage. In The Fashion System, Roland Barthes argues that clothing, like most cultural objects, is imbued with significations that transcend its functionality: a garment easily disassociates from an earlier function to assume numerous new significations (265). The problem with this everexpanding set of meanings, note the authors of “Toward Formalizing Fashion Theory,” is that it destabilizes the ways in which articles of clothing are read and understood, which in turn creates a higher level of risk for wearers as they attempt to conform to fashion's fl uctuating meanings. “Changing adopted styles involves risk to the individual,” they argue, “because a substantial resource investment must be made … and the future meaning, and therefore symbolic utility [of a garment] is uncertain” (Miller et al. 147). This underlying uncertainty is a characteristic of a dynamic and risky fashion process by which individuals determine which new styles to adopt.

Risks in fashion were accentuated during the Longchamp Grand Prix because the event was a well-known showcase for unveiling the newest styles in fashionable garments. Offers historian Marc Gaillard, “[e]very Grand Prix was the occasion for a veritable fashion show at which the greatest Parisian couturiers presented their new designs and society women rivaled each others' elegance” (73). Professional clothing designers began treating the Longchamp races as an opportunity to unveil their newest gowns to a public keen on viewing, and eventually purchasing, the most up-to-date styles. Charles Frederick Worth, the nineteenth-century father of haute couture, famously enlisted the help of his wife, who donned his latest creations to debut them at the Longchamp races (Steele 170). Moreover, because the majority of illustrated publications from the second half of the nineteenth century featured numerous images of spectators at important races, designers could capitalize on the free publicity provided them by the mass-circulating press (Gaillard 101). The Grand Prix racetrack thus provided a milieu that was mutually beneficial for fashionable Parisians and couturiers, although the sartorial pageantry of the event was not without risk. At Longchamp, one could introduce a new fashion to great public acclaim, yet a wearer also risked ridicule should a gown be poorly received, while a designer chanced a devastating blow to his newest design and potential financial disaster in the case of a fashion flop.

I submit that it was this exhilarating combination of social, financial, and sartorial risk that caused Longchamp to become one of the most electrifying sites of fashionable display in nineteenth-century Paris. As it happened, the element of risk at the races was underscored by the very real threat of physical peril present at the track. In 1890, writer Louis Baron juxtaposed the glamour of horse racing with its hazards, describing the event as both “attractive and dangerous” (in Gaillard 129). The existence of corporeal danger was spectacularly captured by several artists of the period. For example, Edgar Degas' 1866 The Fallen Jockey depicts a thrown rider lying unconscious—or perhaps dead—on the track while horses leap over his inert body (Bogg 50). In his 1864 watercolor, Races at Longchamp, Édouard Manet similarly evoked the inherent dangers of a horse race, painting a group of steeds bearing down at the finish line and aiming toward a group of well-dressed

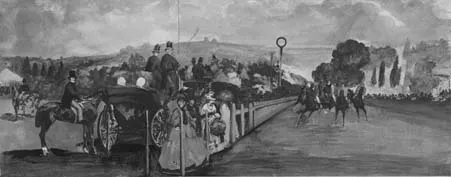

Figure 1.1 Edouard Manet. Races at Longchamp; Verso: Section of Grandstand Area, 1864. Watercolor and gouache over graphite on white wove paper on two sheets, joined; verso: graphite; actual: 22.1 × 56.4 cm (8 11/16″ × 22 3/16″). Harvard University Art Museums, Fogg Art Museum, Bequest of Grenville L. Winthrop, 1943.387. Photo: Katya Kallsen © President and Fellows of Harvard College.

spectators (Figure 1.1). As we shall presently see, interplay between risk and fashion informs the depictions of the track painted by these two artists of Parisian modernity.

FASHION IN HARM'S WAY: ÉDOUARD MANET AND EDGAR DEGAS

In the images of Longchamp seen through the eyes of Manet and Degas, fashion plays a capital role. In Manet's Races at Longchamp, fashion is located literally at the center of the composition. A group of spectators gathered at the track's edge dominates the middle portion of the work, which features several women dressed in the fashionable bell-shaped crinoline skirts of the Second Empire and a number of coach drivers and gentlemen sporting shiny top hats and crisp blue and black coats. Splashes of pink, red, and blue in the stands denote garments and parasols in the crowd and echo the bright colors of the racers' jerseys. The eye is especially drawn to the sumptuous wash of gray and cream-colored fabric of the expansive dresses worn by two of the women in the foreground.

The dynamic action of the scene is displaced to the right side of the painting, where rapid forward motion of the charging horses is suggested both by gray clouds of dust at the animals' feet and their diagonally set front legs. As the horses race toward the onlookers, their sideways momentum sends them careening in the direction of the immobile female spectators in the foreground, who appear to be placed in a somewhat risky position: a line drawn from the hooves of the horse on the front left of the pack and extending into the crowd suggests that the animal is aimed directly at the women, whose pouf skirts appear to be extending out past the very limits of the safety railing that separates spectator from sportsman. Although it is unlikely that the onlookers will actually be trampled by the stampeding steeds, it seems inevitable that, at the very least, the horses will draw close enough to muddy their expensive garments.4 Manet here juxtaposes the wild instability of the horses with the cool stylishness of the chic bystanders. The potential for sartorial harm adds to the excitement...