Between Give And Take

A Clinical Guide To Contextual Therapy

- 432 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About This Book

In this volume, Boszormenyi-Nagy and Krasner provide a comprehensive, sharply focused guide to the clinical use of Contextual Therapy (CT) as a therapy rooted in the reality of human relationships. The authors describe a far-reaching trust-based approach to individual freedom and interpersonal fairness that makes possible a remarkably effective system of psychotherapy. Between Give and Take clearly delineates four basic dimensions of relational reality: factual predeterminants, human psychology, communications and transactions and due consideration or merited trust. It is this last dimension that is the cornerstone of CT. It builds on the realm of the "between" that reshapes human relationships and liberates each relating person for mature living.

Frequently asked questions

Information

Daughter indicates her fear that family members will oppose the exploration of their relationships. | Sarah: At a conference last fall, someone said that it’s really hypocritical to ask families to come and talk about each other if you haven’t done it with your own family. There’s an integrity issue. For example, when I suggest that a client might benefit from therapy, I always say, “I’ve had therapy and it’s really changed my life.” The other thing is if you see connections in your own family, you’re more likely to see connections in other families too. But when I finally called, I found it was scary to ask my own family to come in. |

Emphasizes hidden, relational resources. Implies courage to face option for self-validation through extending concern about the humanity of the other (Dim. IV). Emphasizes positive resources over a search for pathol-ogy. Appeals to the deeper truth of the search for love among close relatives. | Therapist: Well, my experience with my own relatives, as well as with clients, tells me that there’s typically a lot of love and care that often get derailed in families. People get stuck in terms of what they can safely say to each other, what issues they can discuss, what reactions they expect. Each of us builds up a kind of family fiction and loses the humanity of the other person. The issue today is not to emphasize anything negative—all families have negative aspects—but to gently nudge the caring so that some of the harder issues among you can get conveyed. That way you have a chance of getting closer. The problem is that people can love each other and still be distant from them. |

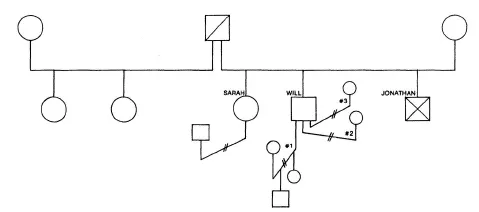

Makes explicit the inclusiveness of therapeutic care and partiality. Thereby begins to define the therapist’s contractual attitude. Elicits daughter’s spontaneity in choosing an area of obvious concern. Directs same partiality towards son as well. | I guess, for me, the people in this room today include the three of you, plus Mr. L and your other son, Johnny. I hope they get incorporated in the discussion because, in many ways, they are here; there’s no way it could be otherwise. Beyond that, Sarah, where would you like to start? It may be one of the areas that you would like to change between you, for example, the anxiety you carry when you want to raise a difficult question. And you might have parallel issues, Will. |

Mother credits daughter’s generosity in giving to people. Yet the childhood example she recalls raises the question of a familial pattern of sacrificial over-giving at the expense of legitimate efforts at self-delineation. | Mrs. L: I’m very proud of what she’s doing, helping people. As a little one she always wanted to do that. My husband didn’t like to go to things at school. She was president of some organization, so I said, “Come on now. This is a dinner and she’s down on the program three times.” We went but she didn’t say a word the whole time we were there, and my husband wanted to know why I had brought him. I asked Sarah why she didn’t speak if her name was on the program. “Oh,” she said, “I had friends who felt terrible because they weren’t included in the program. So I told them to take the time allotted to me.” She’s always helped other people. |

Inquiry into the origins of the pattern and the question of whether giving to people binds them into undue obligations. | Therapist: From whom did she get that, Ms. L? |

Ms. L: My father was a Methodist minister and I think she may have gotten that from him. | |

The parentified daughter intervenes on her mother’s behalf. | Sarah: But you’ve always done a lot for people. Don’t you think so? |

Ms. L: Well, I don’t know. | |

Pattern is connected with self-denial and with the grief over the death of a family member. Acknowledges mother’s giving. | Sarah: I think you gave a lot of parties for people, and for us. You know, I guess w... |

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Prologue

- Half Title

- I. Premises

- Chapter 1 An Orientation to Contextual Therapy

- Chapter 2 The Challenge of the Therapy of Psychotics Background of the Contextual Approach

- Chapter 3 A Dialectic View of Relationship The Development of the Contextual Approach

- II. Outlines of the Human Context

- Chapter 4 The Four Dimensions of Relational Reality

- Chapter 5 Interpersonal Conflicts of Interests A Four-Dimensional Perspective

- Chapter 6 Three Aspects of the Dialogue Between Persons

- Chapter 7 Dialogue Between the Person and the Human Context

- III. Assessing the Context

- Chapter 8 The Client-Therapist Dialogue

- Chapter 9 Assessing Relational Reality

- IV. The Process of Therapy

- Chapter 10 Health, Autonomy, and Relational Resources

- Chapter 11 Rejunction Reworking the Impasse

- Chapter 12 Resistances Obstacles to Therapeutic Progress

- V. Therapeutic Methods

- Chapter 13 A Case Illustration

- Chapter 14 Balance in Motion Crediting

- Chapter 15 Starting Therapy

- Chapter 16 Multidirected Partiality

- Chapter 17 Contextual Work with Marriage

- VI. Applications and Guidelines

- Chapter 18 The Evolving Face of Marriage

- Chapter 19 Divorce and Remarriage

- Chapter 20 Parenting Problems

- Chapter 21 Other Applications of Contextual Therapy

- VII. Therapists in Context

- Chapter 22 The Making of a Contextual Therapist

- Endnote: On Meaning Between the Generations

- Glossary

- References

- Index