![]()

Chapter 1

THE INEFFABLE NATURE OF THE DREAMER

I am, without knowing it, he who has looked on that other dream, my waking state.

—Lois Borges, The Dream

This chapter is based on a dream that I experienced—I should now say “witnessed”—while I was in medical school. It occurred shortly after my mother’s first heart attack and just before her second, which killed her.

Unlike other dreams I had had before, or have had since, this one seemed in some respects to be about the very act of dreaming. What seemed to be different about this dream was its aesthetic beauty, its spirituality, its otherworldliness, the awesomeness of its presentation, and the experience of its numinousness. I felt that this dream happened to me but was not dreamed, that is, created, by me—even though it was. The simple truth occurred to me at the moment of awakening that I could not have dreamed this dream, first because I did not generally speak the way the dream’s characters did and, second, I was asleep at the time the dream took place—therefore, I could not have been its dreamer! I became aware that it was a kind of arrogance to presume that I had had a dream. Instead, I felt that I was privileged to have experienced and witnessed a dream that an “I” I could never know had dreamed! This chapter is my attempt to come to grips with the paradox and mystery of the creation of dreams.

This chapter was originally dedicated to Wilfred R. Bion, whose analysis of my dream was very satisfying; but it is not my purpose here to discuss his analysis of it. What I want to do is explore the mystery of dreaming, a mystery that not even Freud solved, and search for that exquisitely elusive, ineffable subject within us who dreams the dream, the one who lurks on the other side of “the dream’s navel” (Freud, 1900, p. 525).

When Freud (1900) bequeathed to us his legacy—the psychoanalysis and understanding of the dream—patients and laymen generally were so enthralled with this new unraveling of the Linear B of the unconscious that the creating of the dream received little notice among scholars; nor did this matter occupy subsequent psychoanalysts. I was naively baffled by the irony that, although we dream every night, we are fortunate if we can remember any portion of our dreams. Why the discrepancy? If we dream every night but are able to recall only minute portions of our potential dream harvest, then why do we dream at all? I concluded that we are compelled to dream in spite of ourselves. Our understanding of dreams is incidental to—or maybe even helpful to—our mental well-being, but the latter ultimately depends on the fact of dreaming more than on our being able to understand our dreams.

Lowy (1942) proposed that the benefit we receive from dreaming is in no way dependent on our remembering our dreams and that the benefits of dream interpretation are secondary gains. According to Lowy (cited in Palombo, 1978), dreams link current experiences with past experiences:

By means of the dream-formation, details of the past are continually reintroduced into consciousness, are thus prevented from sinking into such depths that they cannot be recovered. Those of our experiences which are not at the moment accessible to consciousness are thus kept in touch with consciousness, so that in case of necessity association with them may become easier.

This connecting function of the dream-formation is reinforced considerably by formation of symbols. When this function takes a hand and condenses masses of experiences, perhaps a whole period of the dreamer’s life, into one single image, then all the material which is contained in this synthesis is reconnected with consciousness. Dream-formation thus causes not only a connection of single details, but also of whole “conglomerations” of past experience. But this is not all. Through the constancy and continuity existing in the process of dreaming, there is created a connection with this dream-continuity. Which fact greatly contributes to the preservation of the cohesion and unity of mental life as a whole [p. 7].

I understand Lowy to be stating that dreams reinforce long-term memory and help to maintain the stability of mental organization by mediating current experiences and matching them with their past prototypes. He seems to be saying that dreams are the silent service of the mind, that they do not need to become conscious in order to do their work. If this is so, then there must be a creator/transmitter of dreams and a dream recipient who receives and processes the results of the dream work. I designate these as the Dreamer Who Dreams the Dream and the Dreamer Who Understands the Dream, respectively.

Palombo (1978) wrote that dreams occur in narrative cycles over time and are computational in their matching functions between current and past information:

An earlier paper (Palombo, 1976) described an autonomous mechanism of unconscious adaptive ego functioning called “the memory cycle.” The memory cycle is a sequence of processes through which new experiential information is introduced into adaptively suitable locations in the permanent memory structure. The most striking hypothesis of the memory-cycle model is that the critical step in the sequence—the step which matches representations of new experiences with the representations of closely related experiences of the past—takes place during dreaming. These new data … demonstrate for the first time the precise relationship between the adaptive function of dreaming in the memory cycle, that is, the matching of representations of current and past experience, and the defensive operations of the dream censorship which act to prevent the matching from taking place [p. 13].

On the influence of psychoanalytic dream interpretation, Palombo wrote:

1. Dream interpretation appears to have a special efficacy in the building of those intrapsychic structures which restore and renew the incomplete self and object representations acquired during the patient’s childhood. This effect results from a synergistic collaboration between the analyst’s interpretive activity and the adaptive functioning of dreaming in the memory cycle. It is distinct from, but complementary to, the role played by dreams in providing new data from that part of the patient’s memory structure which is ordinarily inaccessible to consciousness.

2. The intrapsychic counterpart of the analyst’s dream interpretation is a new dream which incorporates the originally reported dream together with the new information supplied by the interpretation. The new dream, which I have called “the correction dream,” results in the introduction of the information contained in the interpretation into the precise location in the permanent memory structure which contributed its content to the originally reported dream [p. 14].

Palombo, following Lowy, regarded dreaming as an important cognitive component of the memory cycle and therefore an important element in the organizing function of the ego, one that is necessary for memory integration. Similar hypotheses have been proffered by Fosshage (1997), who speaks of “the organizing function of dream mentation,” and by Breger (1977; Breger, Hunter, and Lane, 1971) and Levin (1990). Share (1994), in a carefully constructed piece of psychoanalytic research, finds that dreams can carry the memory of experiences that go back to the first few days of life, and even earlier.

It occurred to me that the production of a dream is a unique and mysterious event, an undertaking that requires an ability to think and to create that is beyond the capacity of conscious human beings. As I began to think along this line, I became dissatisfied with Freud’s explanation that it is the dream work (the primary processes) that creates dreams. I wanted to posit a dreamer within, a preternatural Presence. I began to explore the 19th-century concept of alter ego, or second self, as well as the in-dwelling God of the mystics, the Demiurge of the Gnostics, and even the Muses of classical Greece.

The dream I am about to relate, which I had the night before the final examination in pharmacology in my second year of medical school, is different in many ways from my usual dreams. It was this dream that awoke me to a realization that dreams are, at the very least, complex cinematographic productions requiring consummate artistry, technology, and aesthetic decision making. I began to realize that dreams are dramatic plays that are written, cast, plotted, directed, and produced and require the help of scenic designers and location scouts, along with other experts. The stage of the dream can be likened to a container or ground, whereas the play itself constitutes the content or the contained or the figure (as contrasted to the “ground”). In positing two dreamers—the creator/transmitter of dreams and the dream recipient—I am really proposing the existence of a profound preternatural presence whose other name is the Ineffable Subject of Being, which itself is part of a larger holographic entity, the Supraordinate Subject of Being and Agency.

THE DREAM

The setting is a bleak piece of moorland in the Scottish Highlands, engulfed by a dense fog. A small portion of the fog slowly clears, and an angel appears surrealistically, asking, “Where is James Grotstein?” The voice is solemn and awesome, almost eerie. The fog slowly reenvelops her form, as if she had never existed or spoken. Then, as if part of a prearranged pageant, the fog clears again; but now some distance away, on a higher promontory where a rocky crag appears from the cloud bank, another angel is revealed, who, in response to the first angel’s question, answers, “He is aloft, contemplating the dosage of sorrow upon the Earth.”

The Dreamer Who Dreams the Dream

At the time I had this dream I knew little of Freud and nothing of dream interpretation. I knew only that psychoanalysis existed, that I was drawn to it, and that dreams had meaning. Although the meaning of this dream began to unveil itself in psychoanalysis many years later, I do not want to focus on the meaning of the dream here. Instead I want to call attention to its setting or framework, to its architecture, and especially to its architect or creator.

When I awoke from the dream, I had a strange sense of peace, which I felt contributed to my doing well in the subsequent pharmacology examination, in which I achieved the highest mark. What most arrested my attention then, and thereafter, was the beauty, poetry, spirituality, and mystery of the dream’s presentation. I was deeply impressed, mystified, and bewildered. I knew that I had experienced the dream—that is, I had seen the dream, but I was utterly at a loss to know who wrote it. I wanted desperately to be introduced to the writer who could write those lines. I realized all the while that it could not possibly have been me—because I was asleep at the time!

It began slowly to dawn on me that my dream was a play or a small portion of a larger play, a narrative conceived by a cunning playwright, produced by a dramatic producer, directed by a director who had a sense of timing and of the uncanny and the dramatic moment, and staged by a scenic designer who could offset the narrative of the dream with a setting that highlighted it to the maximum intensity of feeling.1 The casting director also had a flair for the medieval and the romantic nature of theatricality.

I wanted to be introduced to the producer of the short play. I also wished to be introduced to the casting director. Where did he find those particular angels? I began to want to be introduced to the scenic director who chose the Scottish Highlands. He must have known me very well, because Scotland had been of enormous importance to me in my youth. The setting of Scotland and the use of the word dosage were the only aspects of the dream that were familiar to me and belonged to my personal life. Otherwise, the dream was phantastic and mysterious.

The playwright of the dream intrigued me the most and yet most frustrated me because I admired his script but felt so estranged from him. I experienced what Scott (1975) calls the “dreamer’s envy of himself.” The “I” who wrote that dream was admired, envied, idealized, and unknown to me; he might just as well have been somebody else. He is also known as the alter ego, second self, or Other. This is the preternatural, numinous counterpart to the phenomenal subject to which we are more accustomed.2 Together, they constitute the Supraordinate Subject of Being.

Years after experiencing this dream, I encountered patients who were television writers and functioned as story editors. I was introduced to that sophistication of the writing craft which governs the progress of a play from its inception to its first trial response in the creative mind of the story editor, to its modification based on the criterion of workability, and, finally, to the preview prior to the opening night. What makes a dream workable appears to be the result of complex artistic and effective negotiations within the psyche, in the dream’s mixing room, so to speak.

Bion (1962b, 1963), in his concept of the container and the contained, posited that the infant who is contained and the mother who contains him constitute a thinking couple. I believe that Bion’s concept can be extended to include a dreaming couple. In other words, mother’s breast (Lewin, 1950) or face (Spitz, 1965) can be thought of as a dream-screen container, which welcomes the emergence of the dream on its surface. This process can be understood as an externalization within the self of unformulated dream impressions that, when they appear on the dream-screen, achieve a mythic or phantasmal coherence that satisfies “the dreamer who understands the dream” and therefore makes the process work!

Dreams are mercifully disguised to diffuse and suspend the immediacy of toxic meaning and are dramatically vivid, like symptoms, to attract and fix our attention on their themes. Dreams are like archipelagos. Each dream may be unique and specific in its own right, but under the surface we may glimpse the presence of a continuum, the dream of dreams, which is the mythic fingerprint, the unconscious life theme, the theme of themes, for the dreaming subject. Klein (1960), in a footnote to her Narrative of a Child Analysis, suggested that displacement is necessary for the child to be able safely to reveal unconscious phantasies. Perhaps displacement, as Freud (1900) also hinted, is required for the safe exposition of unconscious themes.

An example shows how this story-editor function may work. A patient who was a television writer acted occasionally as a story editor for his show. Once he had to suggest a workable rewrite to an author who was submitting an autobiographical script, but the author refused to submit his story to rewrite. Analogously, in dream work the author presenting the autobiographical reality presents raw, encoded sense data to the dreamer first for “rewrite,” which is a way of saying that in dream work the “photographic” reality is transformed into a narrative that has universal dramatic appeal. A safe alteration of the story must take place. Emphases, deletions, and content changes occur in scripts in the external world; in the internal world, the script is mythified, and the elements of the narrative are condensed and displaced through the use of metonymy and synecdoche. Symbols, both personal and universal, serve as transistors to facilitate the change of the ordinary story into a myth.

In the foregoing example, the writer would not submit his story to rewrite, and therefore the story would not work. Why must the story be rewritten in order to work, and what does it mean that a story works? We humans are so composed and disposed that we believe we must first be able to dream a new reality, or, in effect, re-create it in our own mythic ways, to gain sovereignty over it before it can occur. Thoughts are mental actions, and mental actions are narratives that must first be tried out or previewed (i.e., thought) before real action is possible.

I believe that this rewrite function is instituted by the Dreamer Who Understands the Dream, one of whose functions is self-reflection (Fonagy, 1991, 1995). When a dream story is successfully rewritten, that is, successfully disguised, it still retains the truth of identity implicit in the original story (just as we often recognize almost instantly a friend or relative whom we have not seen for a long time) despite the transformations of age.

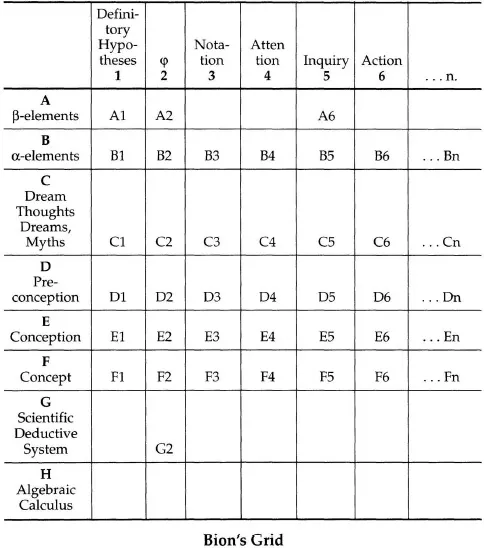

The universal myths, for example, the Oedipus complex, the biblical Genesis, the legend of Christ, are condensed narrative prototypes that first emerged in our primal dawn as someone’s dream and later conjoined with similar dreams reported by others (Vico, 1744; Coles, 1997; Verene, 1997). As I understand the legend of Genesis, it was important for the God-child, having just been born, to imagine that He created all that His eyes opened to before He could allow for the separate creation of His perceptions (see chapter 2). Gradually, the composite dream was formed and became the myth, and the myth became the prototype and palimpsest for all dreams. The myth offers, furthermore, the reassurance known in the law as the principle of stare decisis (let the decision stand)—that there is a precedent to all problems and that the dreamer, if allowed to dream the problems down the vertical axis of Bion’s (1977a) grid3 (the genetic, or, really, epigenetic, axis of thinking), can link the external problem to a soluble mythical problem so as to feel hope for a solution.

Ultimately, the Dreamer Who Dreams the Dream is the Ineffable Subject of Being who registers catastrophic changes and transmits them as a dream narrative to the Dreamer Who Understands the Dream for corrective completion. In an analytic hour we can only marvel at the effectiveness of the Dreamer Who Dreams the Dr...