- 180 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Market Structure and Technological Change

About this book

This book provides a survey of the theory and of the empirical knowledge about the links between market structure and technological change.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Market Structure and Technological Change

WILLIAM L. BALDWIN and JOHN T. SCOTT

Dartmouth College, USA

1. THE SCHUMPETERIAN LEGACY

Any systematic treatment of the literature on the relationship between the organization of industry and technological progress must begin with the pioneering work of Joseph A. Schumpeter. Subsequent studies, theoretical and empirical alike, often identify their topic as yet another contribution to the “Schumpeterian” hypothesis, model, or system. Given the fundamental role of Schumpeter’s thought and the fragmentary portions of his system examined by various subsequent writers, a brief review of his vision and analysis of the interactions among innovation, market structure, and economic progress seems a necessary prologue.1

Schumpeter’s view of the process of innovation in a modern, imperfectly competitive economy is most forcefully expressed in three chapters of his 1942 book, Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy [283]; and this work is the most frequently cited source of the “Schumpeterian hypothesis.” Schumpeter challenged the conventional wisdom regarding monopoly and competition when he asserted that:

As soon as we go into details and inquire into the individual items in which progress was most conspicuous, the trail leads not to the doors of those firms that work under conditions of comparatively free competition but precisely to the doors of the large concerns … and a shocking suspicion dawns upon us that big business may have had more to do with creating that standard of life than with keeping it down. [p. 82].

[T]he large scale establishment or unit of control … has come to be the most powerful engine of … progress and in particular of the long-run expansion of total output not only in spite of, but to a considerable extent through … strategy which looks so restrictive when viewed in the individual case and from the individual point of time. In this respect, perfect competition is … inferior, and has no title to being set up as a model of ideal efficiency. [p. 106].

Schumpeter’s argument is that “the kind of competition which counts” [p. 84] in a modern industrialized economy is most effectively engaged in by “the large scale establishment or unit of control” that does not “work under conditions of comparatively free competition.” There are two distinctly different elements to this hypothesis—a causal relationship between size of firm and innovation, and one between a firm’s market power and its innovative activities. Schumpeter did not distinguish clearly between the two. Rather, he regarded size and market power as inextricably linked in modern capitalist reality, at least to the extent that the primary sources of innovation are involved. This can be seen most readily in his earlier works. In Business Cycles [282], for example, he noted, “But ‘monopoly’ really means any large-scale business. And since economic ‘progress’ in this country is largely the result of work done within a number of concerns at no time much greater than 300 or 400, any serious threat to the functioning of these will spread paralysis in the economic organism.” [p. 1044].

In Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy, Schumpeter did not spell out the significance he attributed to sheer size in the ability of the modern firm to innovate. Perhaps he thought this relationship, as integral as it is to his vision of modern capitalist economic development, is too obvious to require analysis. He did, however, analyze the manner in which market power promotes innovation. The essence of Schumpeter’s argument is that innovation is an activity fraught with uncertainty, and that large-scale innovation may not be attractive unless some sort of “insurance” is available to the potential entrepreneur. Noting that if “a war risk is insurable, nobody objects to a firm’s collecting the cost of this insurance from the buyers of its products,” Schumpeter argued that by analogy a firm unable to obtain insurance against the failure of an innovation should be able to engage in “a price strategy aiming at the same end.” [p. 88]. Thus, monopolistic power in existing product markets may be a precondition for innovation. Further, anticipated market power in new products may provide essential incentives to innovate, since “enterprise would in most cases be impossible if it were not known from the outset that exceptionally favorable situations are likely to arise,” the exploitation of which “requires strategy that in the short run is often restrictive.” [pp. 89–90].

In Schumpeter’s view, “competition from the new commodity, the new technology, the new source of supply, the new type of organization,” was so much more effective than traditional price competition that “it becomes a matter of comparative indifference whether competition in the ordinary sense functions more or less promptly.” [283, pp. 84–5]. Further:

A system … that at every given point of time fully utilizes its possibilities to the best advantage may yet in the long run be inferior to a system that does so at no given point of time, because the latter’s failure to do so may be a condition for the level or speed of long-run performance. [283, p. 83. Italics in original].

In her introduction to History of Economic Analysis [285], Elizabeth Boody Schumpeter noted that “After herculean labor, J.A.S. had finished his monumental Business Cycles in 1938 and sought relaxation in Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy, which he regarded as distinctly a ‘popular’ offering that he expected to finish in a few months.” [p. v.]. As a “popular” work, Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy is intentionally long on vision, and sparing on analysis. To place Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy in its proper perspective, one must recognize that, to a far greater extent than most economists whose scholarly contributions have extended over several decades, Schumpeter’s later works expanded and elaborated on his earlier ones to construct a coherent system with the whole forming a consistent body of thought. (For a thoughtful, integrative exposition of this system, see [39]).

Although Schumpeter did introduce the concept of “creative destruction” in Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy, and noted that competition from innovation “strikes not at the margins of the profits and the outputs of the existing firms but at their foundations and their very lives” [p. 84], he put stress on a short-term relationship in which characteristics of industrial structure were viewed as determinants of innovation. But in his earlier, more analytical work, Schumpeter had concentrated on a longer-term relationship in which the predominant feature is the effect of innovation and its diffusion on industrial structure.

Throughout, Schumpeter distinguished carefully between economic development and economic growth. The latter had been recognized by the classical economists as stemming from population growth and capital accumulation. But Schumpeter was critical of leading economists, including Smith, Mill, Walras, and Marshall, for their failure to incorporate innovation in their formal analyses. “Obviously,” he noted, “the face of the earth would look very different if people … had done nothing else except multiply and save.” Rather, economic development had stemmed from new methods of production and commerce. “This historic and irreversible change in the way of doing things we call ‘innovation’ and we define: innovations are changes in production functions which cannot be decomposed into infinitesimal steps. Add as many mail-coaches as you please, you will never get a railroad by so doing.” [284, pp. 149–59, at p. 152]. Economic development, then, necessarily impacted on industrial structure. As he noted in Business Cycles, “Capitalism is essentially a process of (endogenous) economic change. Without that change or, more precisely, that kind of change we have called evolution, capitalist society cannot exist. …” [282, p. 1033. Parenthesis as in original]. This “endogenous” and “evolutionary” feature of the larger Schumpeterian system has been recognized by a few subsequent modelers, and indeed forms the core of their analyses.

____________

1The distinction between vision and analysis was crucial to Schumpeter’s own thought and to his assessment of other economists’ contributions. He wrote, [285, p. 41], “Obviously, in order to be able to posit to ourselves any problems at all, we should first have to visualize a distinct set of coherent phenomena as a worth-while object of our analytical methods. In other words, analytic effort is of necessity preceded by a preanalytic cognitive act that supplies the raw material for the analytic effort. In this book, this preanalytic cognitive act will be called Vision.”

2. RIVALRY AND THE OPTIMALITY OF INNOVATIVE INVESTMENT

2.1. Measuring the benefits of innovation, with initial insights about how market structure affects the generation of those benefits

The Schumpeterian legacy has fostered exploration of the links between innovative performance and market structure. Market structure encompasses economically important features of the business environment including the number and size distribution (concentration) of a market’s sellers, barriers to entry, firms’ sizes, and diversification. The literature reviewed here seeks to explain how innovations generate social and private benefits in alternative market structures ranging from monopoly to pure competition. Market structure affects the generation of those benefits, because it affects firms’ perceptions of the private benefits and costs of innovation. The purposeful behavior of firms seeking gain then varies with market structure. When social and private benefits and costs diverge, the innovative investment in a market will not typically be optimal.

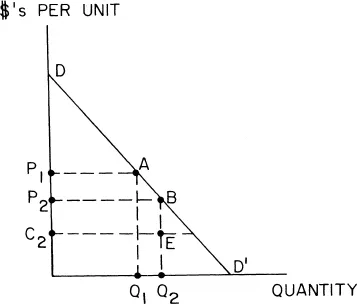

Throughout, research and development (R & D) means firms’ activities directed at the creation of innovations which may be introduced by bringing either new products to market or new processes into production. The benefits flowing from research are the values net of opportunity costs of new products and new processes. Mansfield et al. [186] extend concepts and models used by Griliches [95] and Arrow [7] to define the net benefit of such innovations as the gain in economic surplus. The analysis focuses on three cases—new processes used by the innovating firms, new products sold by the innovator to firms that use the products in their production processes, and new products used by households. In all three cases, the net gain to society is the gain in total surplus. Figure 1 shows the demand curve, DD′, for a final product and its price, P1, and quantity, Q1, before an innovation which reduces the social costs of its production. After the innovation, constant unit social cost is C2, and the quantity and (supra-competitive) price are Q2 and P2 respectively.

If the difference between revenues and costs were nil before the innovation, and if all the social costs of innovative investment are included in the constant unit cost C2, then the net social benefit of the innovation is given by the area P1ABEC2. Mansfield et al. [186] develop the concepts and detailed analysis needed to make this general model operational for each of the three cases they explore.

As Nelson and Winter [219] have observed, using a diagram suggested by Levin [219, p. 116, footnote 4] and reproduced in Figure 2, in a dynamic, progressive, concentrated industry, market structure will affect not only the extent of the deadweight loss traditionally associated with market power. Additionally, the divergence of the best-practice technology from the potential best and the divergence of average practice from best practice will be affected. In Figure 2, C denotes the unit costs for the potential best technology given efficient research; actual-practice unit costs range from ĉ to ĉ′ price is P′ and output is Q′. Then one way to characterize the Schumpeterian question is to ask how market structure affects the cost that arises because best practice diverges from the potential best (area ĉEBC), the cost stemming from divergence between average and best practice (area ĉĉ′F), and the deadweight loss (area AEF) that results because too few resources are allocated to production in an industry where the firms have market power. Potential surplus—area DBC—exceeds actual surplus—area DAĉ′ĉ—by these three types of costs, and their size and significance (as well as their distribution) will vary with market structure.

FIGURE 1

As Mansfield et al. [186, p. 240, footnote 29] observe, the models they develop are not applicable if the innovation’s effects cannot be interpreted as a reduction in social costs. Lancaster’s [139] approach allows conceptualization of new consumer products that are in the same general class as a set of existing products. Products provide a bundle of characteristics, each product being characterized by the fixed proportion in which those characteristics are provided. For expositional purposes, consider the class of products providing various amounts of characteristics Z1 and Z2. Figure 3 shows two such products, A and B. Product A provides two units of Z2 for each unit of Z1, while produc...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction to the Series

- 1. The Schumpeterian Legacy

- 2. Rivalry and the Optimality of Innovative Investment

- 3. Empirical Approaches and Findings

- 4. Diffusion by Dissemination and Imitation

- 5. Conclusion

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Market Structure and Technological Change by W. Baldwin,J. Scott in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.