eBook - ePub

Theory and Treatment of Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia

Biomedical Sociocultural & Psychological Perspectives

This is a test

- 332 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Theory and Treatment of Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia

Biomedical Sociocultural & Psychological Perspectives

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This impressive book presents contributions from leading researchers and practitioners in the field of eating disorders and offers a remarkably comprehensive study of the theory and treatment of both anorexia nervosa and bulimia from biomedical, sociocultural and psychological perspectives. Theory and Treatment of Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia is testimony to the multidetermined nature of the current epidemic of food-related disorders; as such, it emphasizes the pressing need for professionals to collaborate on research and treatment.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Theory and Treatment of Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia by Steven Wiley Emmett, Steven Wiley Emmett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Abnormal Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Biomedical Perspective

Chapter 1

Medical Complications of Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia

Norman P. Spack

The physical appearance of bulimic and anorexic patients reflects their qualitative and quantitative nutritional intake. Whereas anorexic behavior and weight loss usually draw attention to the patient’s “problem,” even if the actual diagnosis remains elusive, most bulimics have been purging themselves for months or years before discovery. In one recent study of college freshmen, 4.5% of the women and 0.4% of the men admitted bulimic behavior (Pyle, Mitchell, Eckert, Halvorson, Neuman, & Goff, 1983). These bulimics maintain themselves at, or even above, ideal body weight and consider purging to be absolutely necessary to achieve any semblance of desirable body weight.

Their apparent external physical normality, however, may belie subtle physical changes, such as dental erosion from gastric acid or parotid swelling. Serious electrolyte losses from the individual or combined effects of laxatives, diuretics, or vomiting (or a superimposed gastroenteritis) render these patients potassium-depleted, with little margin to prevent hypokalemia. At some point of lowered serum potassium, myocardial contractility is affected and a fatal arrhythmia or total asystole may ensue (Keys, Brozek, Henschel, Mickelson, & Taylor, 1950). This catastrophic event probably represents the most common cause of death in bulimics and in anorexics who vomit. It tends to occur in outpatients not subject to the nutritional protocols and biochemical scrutiny of the hospital inpatient unit. Since weight is often the criterion for hospitalization, these outpatients succumb at a weight above that at which they had previously been or would be hospitalized (Bruch, 1971).

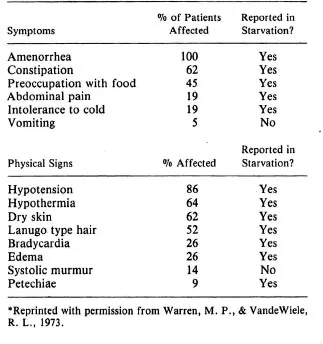

Whereas bulimics may be above or below or even at ideal body weight, the physical similarities between anorexia nervosa patients is striking. The symptoms and physical signs are well outlined in Warren and VandeWiele’s (1973) series of 42 patients (see Table 1).

ENDOCRINE MANFIESTATIONS

Virtually every endocrine system is altered by anorexia nervosa, as it is by starvation. Hormonal concentrations are increased or decreased in predictable fashion, usually proportional to the degree of weight loss. These alterations reflect perturbations in rate of hormonal secretion, degree of binding to serum proteins and receptors, and altered rate of metabolic clearance.

Amenorrhea is a sine qua non for anorexia nervosa with 80% of patients developing it, even before significant weight loss (Warren & VandeWiele, 1973). This finding has been responsible for anorexia nervosa being considered a primary hypothalamic disorder, even though stress alone may account for this phenomenon. Ultimately, when weight loss has been sufficient to reduce total body fat content to less than 20% of total body weight, menses will usually cease for any woman (Eisenberg, 1981; Frisch & McArthur, 1974).

The amenorrhea is the result of reduced estrogen levels secondary to reduced hypothalamic production of the gonadotrophins, LH and FSH. Twenty-four-hour monitoring of LH levels in anorexics reveals secretory patterns similar to prepubertal children, and patients 25%–50% below ideal body weight have markedly impaired LH responses to gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) (Boyar et al., 1974; Sherman, Halmi, & Zamudio, 1975). Even when the amplitude of the reponse to GnRH is normal, it is delayed; similar findings have also been reported in male anorexics (Crisp, Hsu, Chen, & Wheeler, 1982; Vigersky, 1977). Weight-related decreased testosterone levels occur in both sexes accompanied by a diminution in libido (Andersen, Wirth, & Strahiman, 1982; Wesselius & Anderson, 1982). When weight is regained, many patients fail to menstruate at a weight higher than that at which they had lost their menses. Falk and Halmi described this latter group as “more anorexic in their attitudes and behaviors” (p. 799) than patients who menstruated at the attainment of the critical weight (Falk & Halmi, 1982). Although hyper-prolactinemia has been associated with amenorrhea, prolactin concentrations are normal in anorexia and play no role in the hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism (Vigersky, 1977).

Table 1*

Thyroid function tests often appear grossly abnormal. Serum T4 levels may be low due to decreased levels of thyroid-binding globulin, but Free (unbound) T4 levels are normal (Williams, 1981). Under no circumstances should an anorexia nervosa patient be given thyroid hormone on the sole basis of a low serum T4, as the resultant increased metabolic rate will exacerbate weight loss. The most metabolically active thyroid hormone is triiodothyronine (T3) which is generated not by thyroidal secretion but by peripheral conversion from T4. Low T3 levels are the hallmark of starvation and serve to reduce the metabolic rate, thus conserving calories. The TSH response to thyroid-releasing hormone (TRH) is delayed in patients who lose weight (Vigersky, Andersen, Thompson, & Loriaux 1977), and bulimics at normal weight also exhibit a delayed response, one of the few endocrine changes observed in such patients (Gwirtsman, Roy-Byrne, Yager, & Gerner, 1983). The significance of this is unclear.

Growth hormone and cortisol levels are the only hormones typically in the higher than normal range in anorexia nervosa — a finding that is shared with patients starved from other causes. The growth hormone secretory response to arginine and insulin in anorexia is normal, although the response to hypoglycemia may be diminished (Mecklenburg, Loriaux, Thompson, Andersen, & Lipsett, 1974). Increased evening cortisol levels may be secondary to an increased cortisol half-life, a consequence of reduced metabolic clearance of the hormone (Boyer et al., 1977). Decreased affinity of cortisol for its binding globulin also contributes to an elevated free cortisol (Casper, Chatterton, & Davis, 1979).

Growth arrest typically accompanies a reduction in calories significant enough to produce weight loss, and this may be most evident during adolescence when a growth spurt is expected. Peak height velocity antedates menarche by approximately 18 months in normal females, and mean menarchal age in the United States is 12.6 years (Marshall & Tanner, 1969). Despite the wide standard deviation around mean menarchal age, girls who develop anorexia prior to menarche will not only fail to develop estrogen-induced secondary sexual characteristics, but their skeletal age will arrest (despite their elevated growth hormone levels) (Lacey, Hart, Crisp, & Kirkwood, 1979). Crisp (1969) has reported narrower pelvic measurement in fully grown anorexics and has hypothesized that the cause is years of reduced estrogen effect on the pelvic growth centers. No data exist concerning the propensity for such women to require Caesarean sections due to their pelvic narrowing.

The relationship between estrogen deficiency and osteoporosis has been well-established in postmenopausal women and has been associated with an increased risk of long bone fractures (Lindsay, Aitkin, Anderson, Hart, Macdonald, & Clarke, 1976). An increased incidence of fractures and decreased bone density (osteopenia) has also been observed in premenopausal women with surgically-produced estrogen deficiency (Johansson, Kaij, Kullander, Lenner, Svonberg, & Astedt, 1975). Recently, hypoestrogenic anorexia nervosa patients showed similar loss of bone mass (Ayers, Gidwani, Schmidt, & Gross, 1984).

Additional studies will be required to ascertain whether fractures can be anticipated in those anorexics who exercise vigorously. The question of estrogen replacement for anorexics to prevent osteopenia cannot be answered until additional data are known about the natural course of this condition.

Catch-up growth is a frequent concomitant of recovery from illness or starvation in children and adolescents. Height velocities four times normal and bone age velocity three times normal have been reported (Prader, Tanner, & von Harnack, 1963). Whether or not catch-up growth will enable the patient to regain her position on her pre-morbid growth chart depends on the duration of slowed growth and the presence of hormones, particularly gonadal or adrenal-derived sex steroids, which affect the maturational potential of the epiphyseal growth centers in the long bones. Neither the mechanism for catch-up growth nor the signals triggering return to a normal growth rate are sufficiently understood.

Gross and colleagues (1979), in a study of catecholamine metabolism, measured plasma norepinephrine levels, 24-hour urinary 3-MHPG and homovanillic acid measurements in anorexics. Decreased levels were present in all patients who were 20–25% below ideal body weight. All patients were bradycardic and hypotensive, and catecholamine measurements returned to normal with subsequent weight gain. A norepinephrine deficit in the central nervous system may be responsible for the failure of dexamethasone administered at night to suppress cortisol levels at 4:00 P.M. the following day. This is a finding that anorexics and depressed bulimics share with endogenously depressed patients (Carroll, Curtis, & Mendels, 1976; Gerner & Gwirtsman, 1981). Since norepinephrine normally inhibits hypothalamic cortisol-releasing factor (CRF), decreased circulating levels of norepinephrine may allow more CRF to be released, resulting in more cortisol production by the adrenal.

FLUID AND ELECTROLYTE COMPLICATIONS

In a manner observed in severely obese individuals, abnormalities in water balance mediated via a defect in pituitary antidiuretic hormone secretion (ADH) has recently been reported in anorexics by Gold, Kaye, Robertson, & Ebert (1983). Intravenous saline, a potent stimulus for ADH secretion, was infused into anorexics. The ADH response of the patients was subnormal as compared to controls and follow-up studies showed very slow correction with weight gain. This explains the observation of inappropriately low urine specific gravity when anorexics are fluid-restricted. Failure to adequately concentrate their urine renders them even more prone to dehydration at times of heat exposure or incidental gastroenteritis.

In obese volunteers, a defect in renal concentrating ability can be produced after a four-day fast (Macaron, Schneider, & Ertel, 1975). Furthermore, anorexics and starved volunteers fail to adequately excrete a water load, i.e., they cannot adequately dilute their urine, in response to decreased plasma osmolality even when overhydrated (Russell & Bruce, 1966). Thus, anorexics are also prone to edema due to reductions in glomerular filtration rate, renal plasma flow (secondary to decreased cardiac output), and reduced renal-concentrating ability (Berkman, Weir, & Kepler, 1947). These abnormalities have also been reported in malnourished children (Klahr & Alleyne, 1973), but unlike protein-calorie malnutrition, anorexics have a reduced filtration fraction (Aperia, Broberger, & Fohlin, 1978). The qualitative nutritional difference between anorexics and malnourished children may account for the physiologic difference, since protein deficiency is not a typical feature of anorexia.

Some of the fluid abnormalities can be linked to the effect of chronic potassium depletion on the kidney tubule where vacuolation has been associated with decreased urine-concentrating ability (Wigley, 1960; Wolff et al., 1961). Potassium depletion reflects reduced intake of this cation, coupled with enhanced excretion in the urine and stool in the case of diuretic and laxative abuse. Vomiting does not shed potassium through the GI tract as much as it augments urinary loss. Vomiting chloride (hydrochloric acid) produces potassium loss via reduced renal tubular reabsorption of sodium with chloride (as less is available for absorption) and an increased reabsorption of sodium ion in exchange for potassium and hydrogen (Kassirer & Schwartz, 1966). Thus, a hypochloremic, hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis is the renal effect of chronic vomiting. Serum bicarbonate levels higher than 55 mEq/l and occasionally exceeding the serum chloride have been observed (Wallace, Richards, Chesser, & Wrong, 1968). As previously noted, hypokalemia poses a potential threat of reduced muscle contractility. Skeletal, smooth, and cardiac muscle are affected, with muscular weakness, gastric atony and cardiac arrhythmias or asystole being the potential consequences of a profoundly reduced serum potassium concentration. Treating hypokalemia demands slow intravenous administration of potassium chloride, keeping in mind that only a tiny fraction of the total body potassium is extracellular. While a low serum potassium indicates marked depletion of the body’s cation, normal serum levels are no guarantee of repletion.

Sodium values, however, may be low, normal, or high. Overhydration can be conscious on the part of patients who water load themselves to reach a goal weight, or it may be iatrogenic from the overzealous administration of intravenous fluids in patients who fail to excrete water loads adequately. In either case, the hyponatremia may be profound enough to provoke cerebral edema and seizures (Jose, Barton, & Perez-Cruet, 1979).

OTHER BIOCHEMICAL EFFECTS

Other biochemical changes also reflect the idiosyncratic diets and purgatives of anorexics and bulimics. Massive laxative abuse has produced hypophosphatemia (Sheriden & Collins, 1983). Hypercarotenemia is frequently noted in anorexics and in some bulimics and has been linked to amenorrhea even in normal weight individuals for reasons that are unknown (Kemmann, Pasquale, & Skaf, 1983). Patients who vomit are less likely to exhibit such elevated serum carotenes (Bhanji & Mattingly, 1981).

Zinc deficiency has been reported by Casper and by Thomsen who reversed a case of acrodermatitis enteropathica complicating anorexia nervosa with zinc supplements (Casper, Kirschner, Sandstead, Jacob, & Davis, 1980; Thomsen, 1978). Although Casper found hypogeusia in his study of anorexics, the serum levels failed to correlate with the dysfunction in taste sensation. Two separate recent case reports have suggested that oral zinc supplementation has improved taste sensation and appetite in two severely malnourished anorexics (Bryce-Smith & Simpson, 1984; Safai-Kutti & Kutti, 1984). Controlled studies of the effect of zinc supplements in anorexics must obviously be perfor...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Foreword

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Contributors

- Introduction

- Part I. Biomedical Perspective

- Part II. Sociocultural Perspective

- Part III. Psychological Perspective

- Part IV. Conclusion

- Index