![]()

1

The Open or the Closed

De Stijl and Le Corbusier

1.1 De Stijl and architecture

The phenomenon we call ‘De Stijl’ was not an organized movement but a frequently changing collection of artists who rarely if ever met each other and never exhibited together. What connected them and gave them the semblance of a common direction was the magazine De Stijl and the driving personality of its founder and editor, the painter and writer Theo van Doesburg (1883–1931). Although the group's greatest achievements were in the field of painting – above all the work of Piet Mondrian (1872–1944) – Van Doesburg believed that its ultimate field of activity must be architecture. Two years before he died, looking back over the thirteen-year ‘Struggle for the New Style’ in the pages of the Swiss journal Neuer Schweizer Rundschau, he wrote:

It is unquestionably the architectonic character of the works of the most radical painters that finally convinced the public of the seriousness of their struggle, not merely to ‘influence’ architecture, but to dictate its development towards a collective construction. Although in 1917 there was as yet no question of such a collective construction, certain painters attempted, in collaboration with architects (van der Leck with Berlage, I with Oud, etc.) to transfer systematically and coherently into architecture and into three dimensional space the ideas they had developed through painting on canvas. The germ of a universal style-idea was already latent in this struggle to combine architecture with painting in an organic whole.1

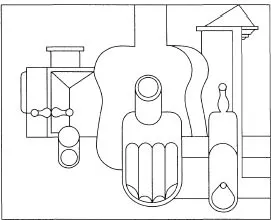

Figure 1.1 C.-E. Jeanneret (Le Corbusier), Composition à lo guitare et à la lanteme, 1920

Consequently Van Doesburg was keen to involve architects as well as painters in De Stijl, and three members of the founding group were architects: Robert van't Hoff (1887–1979), J.J.P. Oud (1890–1963) and Jan Wils (1891–1972). The furniture designer and architect Gerrit Rietveld (1888–1964) joined about a year later. Other original members were the painters Bart van der Leck (1876–1958) and Vilmos Huszar (1884–1960) and the sculptor Georges Vantongerloo (1886–1965).

Despite the inclusion of architects, De Stijl's direct impact on architecture did not get much further than the sporadic collaborations between painters and architects which Van Doesburg mentions. If one excludes sculpture, the movement's total realization in three-dimensional space was pitifully small: some furniture, one or two small houses and a handful of short-lived interiors; the rest remained on paper, as unrealized projects and manifestos. The gulf between this minimal concrete achievement and the movement's revolutionary aims – nothing less than the creation of a new life, a new man and a new world – is either comical or tragic, according to one's point of view. Certainly Van Doesburg, towards the end of his life, saw it as tragic. Reacting to the public's rejection of his interiors for the Cafe Aubette, Strasbourg, which he had struggled so hard to create during 1926–8, he writes despairingly to Adolf Behne:

when the aubette was just finished, before its inauguration, it was really good and significant as the first realization of a programme which we had cherished for years: the total artistic design [gesamtkunstwerk]. yet … the public cannot leave its ‘brown’ world, and it stubbornly rejects the new ‘white’ world, the public wants to live in mire and shall perish in mire, let the architect create for the public … the artist creates beyond the public and demands new conditions diametrically opposed to the old conventions, and therefore every work of art contains a destructive power.2

1.2 An art of destruction

The claim that the aim of art is destruction occurs frequently in De Stijl literature. But what was to be destroyed? In an article which appeared in De Stijl in 1927, Van Doesburg calls for

the total destruction of traditional absolutism in any form (the nonsense about a rigid opposition as between man and woman, man and god, good and evil, etc.) The elementarist sees life as a vast expanse in which there is a constant interchange between these life factors.3

De Stijl's central goal was the abolition of all conventional boundaries, whether in painting, in architecture or in life. The world was seen as a continuum in which all the usually discrete categories merged together: male and female, human and divine, good and evil, inside and outside. In painting, the frame, conceived as the limit of the composition, was abolished. What appeared on the canvas was merely a fragment of a boundless continuity. Applying the same principle to architecture, Van Doesburg declares in the eighth point of his architectural manifesto (1924) that The new architecture has broken through the wall, thus destroying the seporoteness of inside and outside … This gives rise to a new, open plan, totally different from the classical one, in that interior and exterior spaces interpenetrate.’4

The problems arising from De Stijl's aim of replacing the structurally contained, enclosed spaces of traditional architecture with a continuously flowing space in which there was no longer any fixed boundary between inside and outside, or between one room and another, will be explored further in Chapter 4. The purpose of all this destruction – of categories, of confines, of walls – was to help bring about the realization of what was seen as man's future (and inevitable) destiny: the absorption of the individual into the universal. This aim, coupled with the necessity of destruction, appears most famously in the opening words of the ‘First Manifesto of “De Stijl”, 1918:

1 There exist an old and a new consciousness of the age.

The old is directed towards the individual.

The new is directed towards the universal.

The struggle of the individual against the universal shows itself in the world war as well as in today's art.

2 The war is destroying the old world together with its content:

the dominance of the individual in every field.5

It is important to realize, however, that when the De Stijl artists talk about ‘the individual’ they do not only mean ‘the individual personality’, still less ‘the individual artist’. They sometimes mean both of those, but they also mean ‘the individual thing’ in the sense of ‘the particular thing’. The opposition that they speak of between the individual and the universal is really that between the particular and the universal, which is a fundamental concept in classical philosophy. For some philosophers, particulars are primary, and universal are purely mental derivations from particular instances (we derive the general idea of ‘red’ from the experience of particular red things). But for Plato, in contrast, the real world is the world of universal Ideas or Forms, of which the particular things that we experience with our senses are only the imperfect reflections. The latter concept is central to De Stijl theory, where it stems not only from Plato but also from eastern thought (from theosophy in Mondrian's case) and from nineteenth century German philosophy, particularly G.W.F. Hegel (1770–1831), whose influence was absorbed primarily from the leading Dutch Hegelian of the time, G.J.P.J. Bolland. The opposition of particulars and universal will recur throughout this book and is the main subject of Chapters 2 and 3.

1.3 Mondrian: evolution from the individual-natural to the universal-abstract

Humanity's need to transcend the individual in order to evolve towards the universal is a constant theme of Mondrian's writings, where the individual (i.e. the particular) is identified with the natural, and the universal with the abstract. In this context Carel Blotkamp's assessment of the centrality of the concept of evolution in Mondrian's art and thought cannot be improved upon:

To Mondrian evolution was ‘everything’. Not only are his theoretical articles imbued with evolutionary thinking, this concept also generated the process of change that characterized his work to the very end of his life. In order to understand this, we must take into account that in Mondrian's thinking evolution was closely bound up with destruction. He did not view this as a negative concept: on the contrary, the destruction of old forms was a condition for the creation of new, higher forms. Initially this was expressed in his choice of subject-matter, exemplified in the paintings and drawings of flowers in states of decay. Later, in his Cubist period, he came to the realization that abstraction, which implies the destruction of the incidental, outward image of reality, could be used to portray a purer image of that reality, and to represent a higher stage in evolution. And finally, the principle of destruction was applied to the means of expression themselves: his Neoplastic work is, in effect, the result of a whole series of destructive actions.6

The most evident characteristics of De Stijl as style are a direct consequence of this opposition of the universal-abstract to the individual-natural: the straight line replaced the curve, the rectangular plane replaced the solid form, and the six ‘abstract’ colours (red, blue, yellow, white, grey and black) replaced ‘natural’ colour. Mondrian's essay ‘Neoplasticism in Painting’ (De nieuwe beelding in de schilderkunst), serialized in the first twelve issues of De Stijl, is the first, and arguably the most complete, exposition of De Stijl theory. The implications of the Dutch term nieuwe beelding (literally ‘new imaging’), and the inadequacy of the usual translation ‘neoplasticism’, which Mondrian himself introduced, will be discussed more fully in Chapter 2. Meanwhile, except where ‘plasti...