![]()

Physical and Physiological Aspects of Child Development

TANNER:

I am sorry to say that during the next fifteen minutes I am going to make a considerable number of statements without giving you the detailed evidence for many of them. It seems to be the only way I can effectively get across what I have to say, which will really constitute my feelings about the growth process, based entirely on morphological and physiological growth and not on the psychological aspects, about which I have no personal experience. These ideas may or may not clash with the ideas coming from the psychological side.

General

I think anybody who has studied the growth curves of infants and children must be struck by the fact that the whole affair is quite extraordinarily regular. Different external dimensions and different organs grow at different rates, because the head end of the foetus develops in general earlier than the tail end; thus the head after birth grows slowly, the legs, less advanced, grow quickly. But as far as is known each dimension follows a perfectly regular rate-of-growth curve with no breaks or spurts as long as the environment is optimal. The one possible exception to this statement is the mid-growth spurt, an acceleration which may occur and be confined to breadth and width dimensions between about five and a half and seven and a half years. The evidence for its existence is dubious, and the subject needs re-studying on more exact longitudinal growth data. At adolescence a striking growth spurt occurs in all external dimensions except fat. Immediately prior to this adolescent spurt there is a wave of fat increase, followed during the spurt by fat loss.

All this is even true of the growth of single individuals, which after all is almost more than one could demand. There are bound to be variations in any process, yet they are not sufficiently large, short of

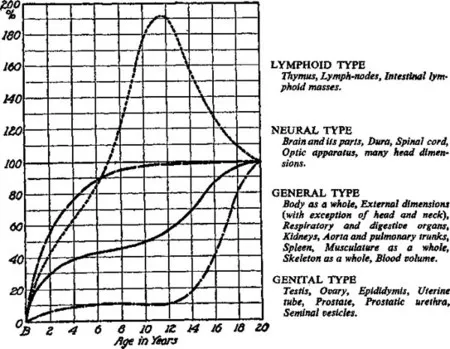

FIG. 1

GRAPH SHOWING CHIEF TYPES OF POSTNATAL GROWTH OF VARIOUS PARTS AND ORGANS OF THE BODY

(From Scammon, 1930, The Measurement of Man, Univ. Minnesota Press)

Curves drawn to same scale by plotting as percentage of adult (20-year-old) values at successive ages

malnutrition and suchlike, to disturb the regular genesis of the curves that one sees. Curves of a smaller period may be imposed on the general curves. For example, there are differences between the seasons; a child grows more in height in the spring and more in weight in the autumn. This is very well established and the magnitude of the effect is considerable, but again it does not disturb the general underlying regularity of the process. I cannot help feeling there is a certain inevitability about growth which forcibly reminds one of the sort of development that, for example, Dr. Lorenz is interested in. The mechanism unwinds; it is not as though it is being pushed particularly to do so, but it just unwinds unless you get in the way and stop it.

Fig. 1 is a very famous illustration from SCAMMON (1930) that many of you will know. It shows some growth curves from birth to age twenty. These four curves are of different tissues, to demonstrate that, though each different part of the human organism has a regular curve, these curves are not all the same. You will see that the growth of the brain and the spinal cord reach the adult level early. What Scammon calls the general type of curve characterizes the growth of most of the external dimensions such as shoulder breadth, width of the chest, height and, approximately, weight. These dimensions grow fairly fast after birth, then they slow down for a while and then have a great spurt at adolescence. There are two other forms of growth illustrated in the figure; there is the growth of the genitalia, which lie dormant until adolescence and then suddenly catch up with the rest of the organism; and there is the growth of the lymphatic tissue which is rather considerably different from the others. The lymphatic tissue grows to a supra-adult magnitude and then at about adolescence it decreases all over the body, even in organs which consist chiefly of other tissues.

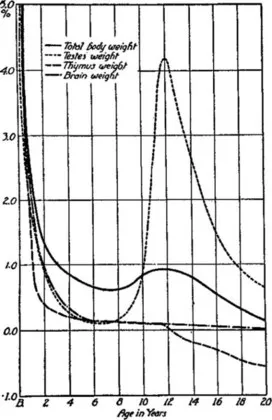

The same events are shown in Fig. 2 in terms of velocity. These velocity curves, that is curves of rate, of growth, seem to me often more informative than distance curves when discussing physical and physiological growth. One can see from this figure that after birth one grows more and more slowly. The brain practically stops growing in magnitude by four or five years old, for example. The growth of the external dimensions—body weight is plotted here, but it could equally well be stature, or some other measurement—decreases also in the same way, but then has the adolescent spurt. The weight of the testes shows a much greater adolescent spurt. Lastly, the thymus and the lymphatic tissues after their initial decrease actually have a negative velocity—as we have seen in the previous figure.

In Fig. 3 are the growth curves of the hip width of a group of girls studied more or less longitudinally. Above is the distance curve, plotting the average width of the hips each year; below is the velocity curve, showing the rate of growth in hip width. The time of fastest growth for a dimension like hip width is before birth, at about six to seven intra-uterine months; after this the velocity decreases steadily except that the decrease is interrupted twice. There may be an increase of velocity at about five and a half to seven and a half years, the ‘mid-growth’ spurt (TANNER, 1947). Then there is the adolescent spurt about whose existence there is no question whatever.

There is one other point worth mentioning before I leave these figures; the mechanism of form change. We do not look exactly the same as we did when babies, and this form change is due to some parts growing faster than others at various times. For example, supposing one believes in the mid-growth spurt; there does seem to be a

FIG. 2

GROWTH CURVES OF FIG. 1. PLOTTED AS VELOCITY CURVES

(From Scammon, 1930, The Measurement of Man, Univ. Minnesota Press)

FIG. 3

GROWTH CURVES OF HIP WIDTH IN GIRLS SHOWING DISTANCE CURVE (above) AND VELOCITY CURVE (below)

After Tanner (1947); Data from Simmons (1944)

difference between growth in length of the body at that time and growth in breadth. Fig. 4 illustrates this. It shows that the velocity of trunk length, arm length, and leg length (above) continues to fall during the mid-growth period while that of hip width, chest breadth, thigh circumference (below), increases.

FIG. 4

CONTRASTED VELOCITY CURVES OF TRUNK-LENGTH, ARM-LENGTH AND LEG-LENGTH (above) AND HIP-WIDTH, CHEST-BREADTH AND THIGH-CIRCUMFERENCE (below) TO SHOW DIFFERENCE DURING MID-GROWTH PERIOD

After Tanner (1947); Data from Simmons (1944) and Boynton (1936)

Nervous System

A few words now about the development of the nervous system. We know very little about this. We lack even the simplest anatomical facts about the development of the human brain, such as, for example, growth curves of the nuclei of the thalamus or hypothalamus. The external growth of the brain approaches completion earlier than any other bodily dimension, and there is little or no new nerve cell formation after birth, or even for some time before. At least this is true of the cerebral cortex, which is the only part about whose growth we have any good information. Very little indeed is known of the growth of the subcortical structures; the times of appearance of the various nuclei and tracts are for the most part unknown. Presumably there is a regular sequence in their development comparable to that of the ossification centres. There is the same ignorance about the development of the sense organs.

By nine months after birth, the brain is 50 per cent of its adult weight, and by two years it is 75 per cent. At about three intra-uterine months the cells become organized into the layers of the cortex, and at about six intra-uterine months the layering and the appearance that we are familiar with in the adult is present. After that the cytoplasm of the cells grows, and the cell processes enlarge, but no new cells, or very few new cells, seem to appear. One can only suppose, of course, that after this time new tracts are beginning to function, connexions are being made, and neuroglia and blood vessels are growing. CONEL (1952) has studied the cerebral cortex from birth to six months and makes one very interesting point: the primary motor area is the most advanced of any part of the cerebral cortex, he primary sensory areas are the next most advanced, and the primary auditory and visual areas follow them. In the case of each sensation the association areas are less advanced than the primary receptive areas. The cingulate gyrus, the hippocampus, and the insula, which are concerned particularly in circuits which include subcortical structures, and as a rough generalization can be said to be concerned mainly with the emotions, are developmentally behind the sensory areas at that time.

RÉMOND:

What do you mean by ‘advanced’?

TANNER:

Conel takes the following grounds. Increase in the width of the horizontal layer of the cells; decrease in number of nerve cells per millimetre; increase in size of nerve cells; increase and differentiation in the chromophil substance and in the neurofibrils. In principle Conel's point is that any particular part of the cortex changes in several ways as time goes by; and when he says that one area is more advanced than the other, he means that the changes are further along in time.

KRAPF:

Is there no reference whatsoever to the myelinization of the fibres?

TANNER:

Yes, he takes nine points altogether as his criteria, and the ninth is myelinization, which he regards, if I understand him, as not one of the most important.

That brings us to the end, as far as I am aware, of the information on the growth of the nervous system. It does not appear to have an adolescent spurt like most parts I mentioned. The skull, as a matter of fact, does have quite a little adolescent spurt, but it is said that the brain does not—I do not see how anybody can tell, with the studies that have been done up to the present time.

Physiological Development

Now I want to go on to endocrinological and biochemical development. There is remarkably little to say, once again. Indeed of all our lacks in the study of the growing child, this is perhaps the greatest. There are no longitudinal studies of hormone excretion or hormone blood levels, except over the span of a single year. There are a few cross-sectional studies from which the course of events is known very roughly. So far as this limited information goes, there is no striking change in hormonal or other internal environment from six months up to puberty. Some parts of the pituitary, some parts of the adrenal cortex, and the gonads do not function until puberty; other hormones seem to be secreted in proportion to the size of the growing child. Striking changes in the internal environment occur at adolescence, however.

One of the more interesting things that I can tell you, I think, is about the adrenal cortex which currently is believed to secrete at least three, and possibly more, sorts of hormones. One of these sorts, the gluco-corticoids, or 11-oxysteroids, hormones which are concerned in the response to stress, are secreted from very shortly after birth at the same intensity as in the adult, per surface area: there is less in absolute amount than in the adult, but then the child is not so big (TALBOT, WOOD, WORCESTER, CHRISTO, CAMPBELL and ZYGMUNTOWICZ, 1951).

FREMONT-SMITH:

Is that based on urinary excretions?

TANNER:

It is based on urinary excretions only.

FREMONT-SMITH:

So we are really still ignorant as to the actual rate of the formation, other than by this indirect method?

TANNER:

That is perfectly true. Although the blood studies that have been done do appear to concur with the twenty-four-hour excretion studies, one must be careful how one argues from twenty-four-hour excretions back to such things as blood levels and rates of secretion.

The neutral 17-ketosteroids, which are in general end-products of androgenic hormones produced in the adrenal cortex and testis, appear to start being excreted about nine or ten, in the male as well as in the female. Some people have referred to this, rather inelegantly, I think, as the ‘adrenarche’. This is an inaccurate term because, as I said, one part of the adrenal has been going hard at it ever since birth. About other hormones we have no information whatever, and I ought to stress the fact that even the information I have given you is very insecurely based and subject to change as methods and data improve.

Now I want to consider interrelations during development. The functional state of a nervous centre may often depend on the internal environment of the body. For example, the nervous pattern of copulation and orgasm is complete in man by early childhood, but is not normally stimulated to action until sex hormones begin to be secreted, and lower its threshold to stimuli.

Conversely the whole train of events constituting adolescence is initiated by the hypothalamus (or by higher centres in the brain). The time of the beginning of adolescence seems to depend on the brain reaching a certain stage of maturation. Possibly the hypothalamic centre responsible is the very last part of the brain to become mature and functional. The postponement of adolescence is seen only in the primates, and seems to be an evolutionary point of some importance (TANNER, 1953).

You know, of course, that sometimes pathologically early adolescence occurs in ...