![]()

CHAPTER ONE

From Manuscript to Monitor

One of the major success stories of Japanese technology during the 1980s was the invention and marketing of word processing technology. This technology had developed much earlier in western countries, where the alphabet posed no significant difficulty, but was for a long time thought impossible in Japan because of the nature of the Japanese writing system. It was not until 1978 that Toshiba succeeded in producing a word processor capable of handling both input and output using characters. In the early 1980s, the technology came within the reach of the average consumer, thanks to rapid advances in the field that led to price falls. There followed an exponentially increasing rise in sales, not just in the business sector but also in the sphere of personal use. This book will tell the story of that growth and its consequences, charting the rapid spread of the technology and its considerable impact on the business, orthographic and cultural practices of its users.

The issue of how to reproduce characters either mechanically on typewriters or electronically on word processors is not of course unique to Japan. It has vexed other countries in East Asia as well, notably China and Korea, both of which have also arrived at electronic solutions. We shall see in Chapter Five some of the difficulties with uniform standards which still remain throughout the East Asian region. This book, however, will deal primarily with Japan’s own solution to the problem. It will present the story of the development and consequences of a technology long desired, rapidly diffused and now enabling Japan to construct a global presence through the Internet.

Patterns of growth

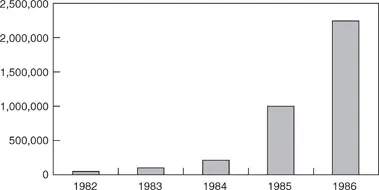

Let me begin by dazzling my readers with sales statistics, which show us clearly how rapidly word processing technology was accepted in Japan after it became available at prices most could afford. The boom in sales of stand-alone word processor units began around 1984. Figure 1 shows the annual sales figures recorded by the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) between 1982 and 1986. We can see that the really big surges took place in 1984, 1985 and 1986, as advances in computer technology and economies of scale made possible by mass production combined to lower prices. At around this time, words like personal computer, word processor and database came into common use in everyday discourse; the word waapuro or wapuro (short for waado purosessaa, the Japanese equivalent of ‘word processor’) figured prominently in speech and writing as debate about the new writing technology escalated. So often were the stand-alone machines advertised, one writer commented wryly as early as 1983, that the advertisements made the national dailies look like trade papers for the electronics business (Sakai 1983: 3). One year later, another observed that it would by then be rare to find someone who did not have a word processor in the home or in the workplace (Fujisaki 1984: 111). That was clearly an exaggeration, but the perception nevertheless reflects community astonishment at the popularity of the new machine. The same writer predicted an increase in sales figures from 300,000 in 1984 to an estimated one million by the end of 1986. In fact, the MITI figures given in Figure 1 show that the 1986 sales were more than double this estimate.

Figure 1: word processor units sold 1982–1986 (Source:

Daijin

1987: 226)

By 1986, 90% of businesses were using word processing to produce Japanese-language documents (

Daijin

1986: 448). Of the total number of word processors in circulation the following year, however, close to 90% were for personal as opposed to office use. Citing an Asahi Shinbun article from April that year which reported that close to three million families owned a word processor, researcher

Orie calculated that on the basis of government figures for the number of households in Japan, that meant about one in twelve households. This study further found that prices and functions had also changed to the extent that companies now changed models about every six months (

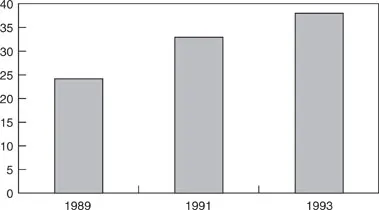

et al 1987: 63). By the beginning of 1991, a survey by the Economic Planning Agency found that one in four people possessed a word processor (Aoyama 1991: 217). Later figures for the 1991 financial year indicate that 32.6% of all households owned a word processor that year; by 1993, this had risen to 37.8% of all households (see

Figure 2).

Once the perception of students as a potential market took hold in the mid-’80s, prices dropped still further, but at the same time the range of available functions increased. Word

Figure 2:% of households owning word processors 1989–1993 (Source: Japan Statistical Association 1992: 548 and 1995: 588)

processors and computers using word processing software then began to make their impact felt in schools and universities as well, with an increasing number of institutions requiring student assignments to be printed out rather than handwritten. By 1993, a Tokyo survey revealed, 20.5% of primary-school students and 22% of middle- and high-school students had computers at home, while 47.3% of primary-school students and 46.3% of middle- and high-school students had stand-alone word processors (Nakajima 1993: 666).

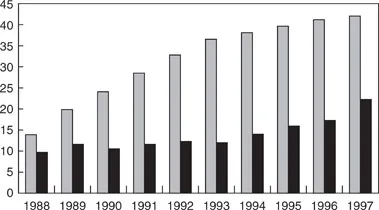

The opening of the Japanese market to American computer companies began with the ‘Compaq-shock’ in 1992 when clones made by Compaq arrived in Japan at half the price of the local NEC machines. This has increased the number of those who prefer to use word-processing software on a PC rather than a stand-alone word processor, seeking both the wider range of applications a PC allows and, more recently, Internet access. Figure 3 compares households owning standalone word processors and personal computers between 1988 and 1997; by 1994, the PC component was beginning to increase, though many more households owned word

Figure 3: comparison of households with word processors and personal computers, 1988–1997 (Source: Economic Planning Agency 1997)

processors than PCs. Note that these figures are for ownership, not annual sales — there is nothing to tell us when the word processors were bought; many may have been bought as much as several years earlier. If we look at actual sales figures, we find that annual sales of stand-alone word processors peaked in 1991 at 2.6 million units. In 1994, PC sales surpassed those of word processors for the first time by a large margin (1,123,900,000,000 yen as compared to 187,100,000,000 yen), prompting Abe Keisuke to speculate in the Asahi Yearbook that 1994 would eventually become known as pasokon gannen (the first year of the PC’s reign). The following year, annual sales of word processors dropped below two million for the first time in ten years (Abe 1995: 290).

The first half of the 1990s, then, saw growth in the sector of word processing packages used on PCs at the expense of the stand-alone word processor, although the latter continued to be popular because of its easy portability and all-inclusive nature. Japanese companies began to invest more in information technology about this time, and the PC also began to spread widely among individual users, spurred by interest in the Internet. (There is still a long way to go, however, before PC diffusion in Japan rises to the levels found in America and Australia: in 1997 only around 20% of Japanese had PCs, compared to over 40% in the United States and about 35% in Australia.) (International Telecommunication Union, 1998). The early 1990s also saw the appearance of Japanese versions of Word Perfect, Word and other word processing software for use on these computers, starting with the release of a Japanese version of Windows 3.0 in 1991. Japan also began to establish a sizeable presence on the Internet, after a slow start caused by confusion among the ministries responsible for national communications policy. By July 1998, JP top-level domain names ranked fifth in the number of hosts supported on the Internet (Network Wizards, July 1998), and as of August 1998, the Japanese language was the second most widely used language other than English on the Internet after Spanish (Global Internet Statistics 1998). Japanese language versions of different kinds of software have proliferated, including Internet packages: the Japanese version of Internet Explorer 5, for example, was released in March 1999. None of this rapid growth in Japan’s presence on the Internet would have been possible without the invention of word processing technology.

Why the script delayed the technology

What lies behind the astonishingly rapid spread of this technology both within and outside the business world? Part of the answer lies in the novelty of the technology itself, in that for the first time the long-standing and seemingly intractable problem of how to produce printed documents in Japanese had been addressed in an effective and realistic manner. Perhaps the best way to appreciate the significance of this breakthrough is to compare the English-language experience with that in Japan.

Ten years ago, when I wrote for publication, I wrote in longhand which was later typed up on an electronic typewriter. Since then, along with just about everyone else I know, I have progressed to using a computer word processing program which enables me to create, edit and print a document with much greater ease and in a much shorter time. It never occurs to me that there is anything particularly remarkable about the process: I simply take it for granted that if I type in the letters r-e-m-a-r-k-a-b-1-e, the word ‘remarkable’ will appear immediately on the screen and eventually in the printed text. And indeed, there is little to wonder at, in the case of languages such as English that use an alphabet, that input so readily translates into output.

When a document produced on a Japanese word processor rolls out of its printer, however, it represents a significant victory over considerable obstacles. The reason, of course, lies in the nature of the Japanese script. Modern Japanese is written using a combination of three scripts: kanji (Chinese characters) and two phonetic scripts, hiragana and katakana. This situation came about because characters, imported around fifteen hundred years ago from China in the absence of any native orthography, could not be used efficiently on their own to write Japanese; they had originally been developed to suit the requirements of a language with markedly different features (see Miller 1980 for further details). The two phonetic scripts were therefore eventually developed in Japan to address the problem of how to indicate not only the pronunciation of Japanese words (which of course the Chinese characters could not do) but also the verbal and adjectival inflections and postpositions not found in Chinese. Both scripts now represent the same forty-six short syllables.

Over the centuries, texts have been written in varying combinations of the three scripts. Today, Japanese texts are written in a blend of Chinese characters, hiragana representing native grammatical features or in certain words which convention decrees are not written with characters, and katakana for foreign loanwords, foreign names (other than those of Chinese origin), domestic telegrams (when those were still in use) and for emphasis. While there are many thousands of characters available, the current script policy document of the National Language Council recommends 1,945 of the most commonly occurring for general use, and these are the guidelines followed by the Education Ministry in schools. In practice, around 3,000–3,500 characters are needed to read newspapers, advertisements and other sources of text encountered in daily life (Seeley 1991: 2; Tanaka 1991: 59–60).

A simple example will illustrate how this system works and will lead us to an understanding of why machine production of documents has until recently proved so difficult in Japan. Take the sentence

Kyanbera to iu toshi wa

no shuto desu

Canberra is the capital city of Australia.

Here ‘toshi’ and ‘shuto’ are nouns meaning ‘city’ and ‘capital city’ respectively; ‘Kyanbera’ and

are proper nouns giving the name of a city and a country; ‘to iu’ indicates that the name of the city referred to is Canberra; ‘wa’ is a case marker indicating that the word which precedes it is the topic of the sentence; ‘no’ is a possessive marker; and ‘desu’ is the verb ‘to be’, meaning in this context ‘it is’. As can be seen from the Japanese version, ‘Kyanbera’ and

are written in the angular katakana script because they are foreign place names; ‘toshi’ and ‘shuto’, both nouns, are written with characters; and the grammatical particles, ‘to iu’ and the copula are written in hiragana. In order to write this sentence by hand, one must remember and correctly reproduce four characters interspersed with hiragana; write two words in katakana; and remember that the particle ‘wa’, in a carryover of prewar usage, is traditionally written with the symbol for ‘ha’.

Suppose the sentence had included a verb other than the copula, such as for instance:

I often drink coffee

Here, the first syllable of the word ‘nomimasu’ ([I] drink) is written with the kanji logograph for ‘drink’, and the remainder of the word, including the non-past suffix, is written in hiragana. The adverb ‘yoku’ (often) is these days also written in hiragana. So is the object-marker postposition ‘o’, although it is traditionally written with the symbol for ‘wo’, the only use to which this particular symbol is now put. While there is a certain amount of free play involved in the substitution of hiragana for characters, depending on context, these simple examples demonstrate what has become the clearly defined pattern for the interwoven use of the three scripts in postwar Japan.

, a loanword, is written in katakana.

Navigating the interplay between the three scripts in writing by hand, intricate though it seems to onlookers, poses no particular difficulty for Japanese themselves once they have learned the system. The two phonetic scripts present no particular challenge, being simple to learn and to use. What can seem problematic is the use of Chinese characters, specifically the burden on memory produced by the aggregate of the size of the character set and the multiplicity of its uses (one character may have several different pronunciations depending on the context in which it occurs). In writing by hand, one faces issues such as remembering the correct number of strokes in a character in the correct spatial relationship, recognising which of several similar characters is used in a particular word, and in general being able to call up from memory the required characters, how...