This is a test

- 196 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Organizations do not have goals – only people do. Furthermore, people within the same organizations have different goals. This book takes this as its starting point, recognizing that organizations are a dynamic coalition of individuals and groups competing and co-operating as they each pursue their various objectives. Power is a fundamental part of organizational behaviour but many previous studies failed to recognize its centrality. This book remedies this.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Organizational Behaviour (RLE: Organizations) by Robert Lee,Peter Lawrence in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Comportamento organizzativo. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

PART ONE

UNDERSTANDING ORGANIZATIONS:

1 Classical, human relations and systems approaches

2 Contingency theory and politics

In this first part of Organizational Behaviour: Politics at Work we will take two chapters to review the development of ideas about organizations. This is a necessary stepping stone on the way to understanding people in organizations. We will see that there are several different ‘organization theories’ which provide a range of different frameworks for thinking, and help us to identify some of the key concepts to be given more detailed treatment later. We will see how organization structure, individual motivation, group behaviour, interpersonal influence, and other important facets of organization life have formed parts of the major theories of other writers, and we will discuss the strengths and limitations of each perspective.

In the latter part of Chapter 2 the reader is introduced to the political perspective which underlies the body of the book. By then he will have learned about earlier perspectives and will be able to fully appreciate how the new approach differs.

1

CLASSICAL, HUMAN RELATIONS AND SYSTEMS APPROACHES

In this chapter we briefly describe the development of organization theory. The ‘Classical’ ideas of early management writers are discussed and the ‘Human Relations’ approach is introduced as the foundation for modern OB. The widely used ‘Systems’ theme is explored and presented as underpinning the conventional wisdom about organizations. The term ‘managerialism’ is explained and its consequences examined.

Organization theory

Organization theory is the study of ways of thinking about organizations. Within this subject area there are many different schools of thought, with a range of contrasting and conflicting ideas, and we shall be examining three of the major ones in this chapter.

Some of the important questions which any theory of organizations must tackle are:

• What are the key variables which determine what happens in organizations?

• What goals does, or should, an organization pursue?

• How is the organization co-ordinated or bound together?

• What assumptions can we make about the motivation and behaviour of the people in the organization?

Everyone who has experience of formal organizations has some kind of organization theory. It may be implicit, only part formed, inconsistent, but it is none the less there, influencing the individual's perception of what goes on around him and his behaviour. When the individual is a manager it is important for him to be aware of his personal theory in order that he can act reasonably in a range of situations, and also develop his ideas as new experiences provide feedback on how useful his view of the organizational world is. Without this kind of personal organization theory the manager would just respond unpredictably to new circumstances and would be unable to make sense of the complex environment in which he works.

A rethink: The manager

A Manager is someone called a Manager. The term is, in fact, hard to define. Often, it means that he supervises other employees or is in charge of important systems or tasks, but this may also be true of employees who are not called Managers.

Sometimes a Manager is thought to have particular responsibilities for ‘efficiency’, ‘productivity’ or ‘profit’. He is seen as part of the company rather than a mere employee who works for it.

In political terms a Manager is simply someone with the title. But we should note that it tends to carry with it certain powers and privileges. Managers usually earn higher salaries than non-managers and often have better conditions of employment. Managerial job descriptions often specify rights to spend money, recruit people, give orders and other such useful, political possibilities.

Managers are often ambitious. This means they wish to rise up the formal hierarchy, acquiring more power and privileges on the way. In order to reach the higher levels they may have to conform to the behaviours desired by those who are there already. This may mean wearing the right clothes and expressing the right beliefs, as well as achieving the right levels of performance. On reaching the higher levels the Manager may be able to change organizational systems to influence the behaviour of those around and below him. Until that time he will usually wish to at least seem to be conforming to expectations, otherwise he is unlikely to progress.

Different writers on organizations also have their individual theories. To simplify study of their ideas we assemble them into ‘schools of thought’ – groups of people with similar answers to the questions asked earlier. They tend to have attitudes in common and make comparable assumptions. This is an oversimplification because often writers within each school are at odds on some points but it is still a useful way to structure our thinking.1

The classical approach to understanding organizations

During the nineteenth century the environment of economic organizations changed drastically. Technologies became more sophisticated and their rate of development began to increase; markets became more competitive as other countries industrialized and as customers became more discerning; trade unions emerged as a force in both politics and industry and the government itself began to influence the activities of organizations more and more with laws and economic measures.

The Limited Liability Acts passed in the mid nineteenth century in Britain meant that investors did not have to become partners and risk their total wealth. They could buy shares and only involve themselves in the business to the extent of making that limited financial commitment. It was this development, coupled with the need to cope with the increasingly complex environment and the increasing size of organizations, which led to the emergence of a new ‘managerial class’. These people, while not owning a significant part of the organization, had the power to control it. It is this managerial class which nowadays, by its cumulative actions, exerts perhaps the greatest influence over the nature of our society.

The first view of organizations which we must examine is that put forward by their earliest spokesmen. In part it reflects the needs of the day and the different environment of organizations in an earlier period; this makes the model appear oversimple but it is where our forerunners started, and it is where we must start, not just for historical reasons but because the past has had a formative effect on the present.

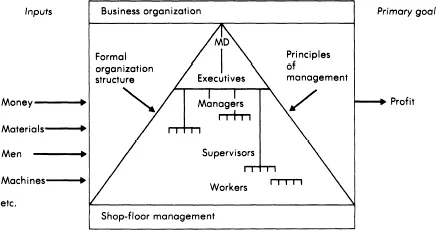

The early ‘spokesmen’ for the new managers were usually experienced and successful managers themselves. They were aware of the problems of their colleagues in coping with the new circumstances we have outlined, and they attempted to synthesize their experience systematically into an easily learned model of the organization and a simple set of rules for improving its performance. This is known as the classical approach and it is represented in Figure 1.

The classical view portrays the organization as an instrument for making profit for the owners. The purpose of management is to convert inputs – men, money, materials, and so on – into profit via good managerial practice.

Figure 1 The classical model

Some writers focus on the ‘shop-floor’ end of the organization, concentrating on the jobs people do, the payment systems, work layout, supervision and related areas. The most influential ideas on these subjects originated with an American, Frederick Winslow Taylor, whose work we shall briefly examine.2

The other group of classical writers deals with the higher management levels of the organization. These writers are mostly concerned with formal structure (or hierarchy) and the processes of general management. They attempt to specify a number of principles which should be followed if efficiency is to be achieved. Most later writers in this genre have built on the work of a Frenchman, Henri Fayol.3

Shop-floor management – F.W. Taylor

F.W. Taylor served an engineering apprenticeship from 1874 to 1878. He took a Mechanical Engineering degree and then became a chief engineer for the Midvale Steel Company, eventually moving to become general manager of a paper mill. In 1893 he opened an office in New York as a consulting engineer and it was after this that his ideas on what he called ‘scientific management’ were published. He is probably the best known and most influential of all management theorists.

Taylor's first major concept is the separation of planning from doing. Employees were seen as unsuited to the making of decisions in terms of both ability and motivation. Planning and decision-making should be passed up the hierarchy to the better qualified managers who will have the best interests of the company at heart.

This leads directly to the second major idea, job design. Taylor believed in the maximum fragmentation of work. Tasks should be divided into their simplest possible constituent elements and each worker should do as few elements as can be conveniently combined into a job. This de-skilling process was seen to have advantages such as minimizing training time, making recruitment easier, making it easier to organize work into flow lines, and removing undesirable decision-making from shop-floor workers. There would be less problems to cause errors, and workers could become incredibly quick at their simple tasks.

There can be no doubt that the widespread application of this philosophy has led to great improvements in productivity. There are problems associated with it, however. Workers doing simple, undemanding tasks may become unsatisfied, bored, frustrated with their jobs and antipathetic to the company. This can lead to a range of human and industrial relations problems. In the 1980s we are witnessing a technological revolution in which microprocessor-based machines are taking over many Taylorian routine tasks. The long-run effects of this process are still the subject of speculation.

Simplifying jobs paves the way for what is perhaps Taylor's greatest contribution to management – Time Study. Time study involves a number of different techniques for calculating how long a qualified worker of average ability and motivation should take to do a job. Nowadays it has been developed into a very fine art and is combined with Method Study aimed at finding the best method for doing the job. Times from time studies are useful for calculating such things as costs, delivery dates, and machine loading, as well as for balancing the work done by each operator on a flow line. For Taylor, however, the main purpose of these times was to form the basis of payments by results systems.

If we know how long the average worker should take, then we can pay people more if they work faster and less if they work slower. In terms of motivation the assumption is that people will work as fast as they can to earn as much as they can. This may, to some extent, be a self-fulfilling effect of ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Structure

- ‘Boxes’

- Political Man

- Part One Understanding Organizations:

- Part Two Developments in Organizational Behaviour

- Part Three Influencing Behaviour

- Epilogue

- Index