![]()

Chapter 1

What is Organisational Economics?

First of all, we take economics to be that social science which studies the employment, production and distribution of scarce resources which have competing uses. We take an ‘organisation’ to be a system of consciously co-ordinated activities of two or more persons explicitly created to achieve specific ends.1 Both of these definitions are complex and full of problems. For immediate purposes, however, only a few clarifications are necessary. It is important to make clear that we are concerned with organisations of an intermediate kind, namely those below the level of national government but above that of the individual household or family. This principally means private firms, nationalised industries, local authorities and charitable and voluntary enterprises. Such organisations are all particularist. That is to say, within a given nation state they all pursue sectional interests in varying degrees. Together they account for most of our employment in Western societies, most of our physical production, a large part of our public and welfare services, and much of our social life. The resource allocating systems and behaviour of such intermediate organisations have traditionally been the lifeblood of micro-economics.

ORGANISATIONS VIEWED ECONOMICALLY

By their nature organisations, even quite small ones, are highly intricate. They can be studied as formal and informal systems, from the viewpoints of structure or process, using static or dynamic models, sociologically, psychologically, politically, managerially. Like these other approaches, economics necessarily abstracts from a complex reality. From all the rich complexities of organisational development and activity economics picks out a single guiding theme. Although this theme is a partial one, and certainly makes no pretence of explaining organisations as a whole, it is vital and all-pervasive.

Economics views an organisation's decision making as an act of choice which deploys resources of manpower, managerial skill, money and materials which are usually scarce. Such choice consequently diverts these resources from other uses to which they could be put, either by the organisation itself or by others. In one well-tried model, economics sees the organisation as a transformation system, taking precious human, material and financial resources (the ‘inputs’), working on them in various ways and then performing various activities, distributions or services (the ‘outputs’). Thus the organisation makes difficult choices in deploying resources internally. It also relates dynamically to the environment, on the one hand taking resources and imposing costs and, on the other, providing goods or accomplishing tasks which may benefit the community. But at all points the organisation is influencing the disposition of scarce resources.

Let us take a simplified illustration. A large company, a local authority or a charity is considering major changes in its activities, perhaps as part of some annual budgeting or planning exercise. Note that the concept of such decisions taken explicitly and at a single, definable point of time may already be an abstraction. In practice, the organisation's decision making will probably be more messy and fragmented than this implies. But accepting the simplification for the moment, there are many angles from which the strategic decisions under consideration can be viewed. The decisions can be regarded as a problem of human relations, psychology or communications. For example, who actually makes such decisions in the company, local authority or charity? Whom do they consult and why? What influence is played by formal and informal pressures, behaviour patterns, organisational structures or morale? Again, the decisions can be viewed technologically. What are the physical production possibilities of producing and delivering the relevant goods and services? For example, the company may be considering buying new equipment or making a new product, the local authority may be trying to decide priorities between public housing or services for the elderly. Technical problems will then arise of just how much can be done with given sets of resources, for example the physical capacity of plant to turn out products and of land to sustain building densities. A further and related aspect is that of quantifiability. Accountants will be on hand to measure and advise on cash flows. Statisticians and operational researchers may be needed to manipulate the quantifiable data mathematically as an aid to decision making.

These human, technical, accounting and quantitative aspects are important and we will often refer to them. But the economic viewpoint is different. It concentrates single-mindedly on what happens – relative to scarce resources – in, and as a result of, the very act of choice. In particular, how pressurised or scarce are the resources under consideration relative to the organisation's goals or society's? Such scarcity will incidentally be measured only imperfectly by their money prices, if any. Are the decision makers aware of the other uses to which the resources could be put, at least by the organisation? How far is their decision making about the resources rational, clear, explicit and consistent in terms of the sheer logic of choice? How will the efficiency of their choice be judged by themselves, by their peers or by society? What people are going to benefit or lose out by the choice relative to other alternatives? What other choices might be made if, for example, the internal decision making process was organised differently, for example if the organisation were differently owned or controlled or larger or smaller, or if the activities were co-ordinated by grants and taxes rather than markets, or the other way round? And what predictions can be made about resource allocations under these varying conditions?

To return to our simplified example. In pursuing major changes the company, local authority or charity may well have to recruit more people, get hold of more land, raise cash from government, the capital market or supporters. In so doing it will almost certainly divert these resources from other organisations and other existing or possible uses. Having got hold of the resources, the organisation will then use them more or less fully – in a very inefficient case just sitting on them for long periods! Alternatively, the people in charge may feel that they have enough resources just for the moment and of course they may simply be unable to get any more anyway. But in both the last cases, in deciding to pursue one activity rather than others, the organisation will be making a further diversion of resources, this time ‘internally’. For example, the company could produce more refrigerators but at the cost of fewer washing machines, the local authority more housing but at the cost of fewer public libraries or refuse collections. For that matter the charity could help more people in Newcastle but perhaps fewer in Biafra. Moreover, the element of sacrifice and choice may also relate to time. If big investments in new factories or housing are decided upon, in the long run this should respectively help the company or people on the housing waiting-list. But in the short run it is likely to mean sacrifices, perhaps less cash for the company's shareholders or workers, fewer current services for the local authority's ratepayers.

These are only a few of the economic issues that will arise. Moreover, in each case economics will have a lot to say about such questions as, how big are the actual sacrifices, gains or trade-offs? How can they be measured? Should they be made explicit and if so by whom? Not least, what concepts can help in deciding what is the ‘best’ thing to do – and then, afterwards, whether the ‘best’ thing has been done?

SCOPE OF ORGANISATIONAL ECONOMICS

We should now be more precise about the scope of our subject. First, we cannot consider organisations and their decision making from economic viewpoints without paying careful attention to the allocation systems within which they are set. The concept of an allocation system may need clarifying. Allocation systems are not, of course, separate from social systems but simply represent a way of looking at social systems, whether these be co-operatives, clubs, municipalities, corner shops or giant businesses. The concept of an allocation system helps us to look at social systems from the specific viewpoint of how they carry out their economic role, that of allocating scarce resources. An important part of our subject – and a persistent theme of this book – is the classification, comparison and understanding of these allocation systems. This includes the interplay of power and coercion, exchange and self-interest, and social benevolence, working through complex systems of markets and grants, bureaucracies and electoral choice.

Next, our subject brings us closer to the guts of decision making in boardroom, council chamber or director's office. In deciding on important changes, organisations are not only bounded by wider social systems, they are also influenced by their own objectives. But economic problems also arise about these objectives. To imagine that economics is only about ‘means’ and never about ‘ends’ is of course completely false. For not only will an organisation's objectives interrelate with its allocative environment, at any point of time its objectives are extremely unlikely to be mutually consistent. On the contrary, they will often conflict. Just as a national economy is caught in the toils of choices or trade-offs between, say, full employment and stable prices or between public and private consumption, so a business may have constantly to juggle its short-term profit against long-term profit objectives. So, too, a public body at grass-roots level may be torn between its speed and efficiency objectives, say, and the need to consult local opinion. Therefore, in a real sense corporate objectives, also, have to be economised. Relative to available resources, various trade-offs between objectives will exist. Although the final choice of objectives is the prerogative of decision makers rather than economists, the latter frequently contribute advice on what priorities or combinations of organisational objectives may be possible.

Organisations are complex systems in which component parts relate to each other and also to the whole, and in which decisions about the short-run, the medium-run and the long-run are inextricably intertwined. Organisations are also open-ended systems, closely related to their outside environments of suppliers, customers, local citizens, central government etc. Even apparently small decisions are often highly general in their implications. For example, the decision inside a large company whether to replace a little old warehouse in Piddlington relates to its requirement for stock-holding. The company's stock-holding system may have been wrung through a computer but the levels of stocks anticipated relate to its production plans and, more particularly, to its estimates of future sales. Still more important, the company's estimates of future sales relate in turn not only to its market forecasts but also to its market strategy. What share of the market is it aiming at and why? Finally, market strategy relates to overall strategy and objectives. How does the company see its constraints and opportunities, whether in terms of finance, labour and other resources, competition, political forces or managerial abilities and aims? All these questions clearly interlock. Moreover, the interlocking character of organisational activities extends no less to, say, a large local authority, a hospital or a housing association.

An advantage of micro-economics is that it offers principles in the light of which virtually all types of decisions can be viewed. These economic concepts are few in number and broad in scope, yet also sufficiently clear-cut to create some order out of a complex scene. Each of the main micro-economic principles can be applied, in varying degrees and forms, to virtually all sorts of decisions. But they also provide ways of looking at decision problems which are interestingly distinct. So a lot of attention must be given to these basic ideas and how they can be used in practice both by student observers trying to make sense of organisations from the outside and by the internal decision makers.

Finally there is the wider social dimension. As explained so far, organisational economics mainly concentrates on the existing activities and objectives of organisations and on how they can pursue these more efficiently. But the social effects of organisational actions, for both good and ill, cannot be ignored in an interdependent society. This is so whether or not such effects are taken into account by the organisations themselves. If organisations pollute the atmosphere, ruthlessly conflict with each other to the detriment of public objectives, pursue corrupt or unethical practices or ride roughshod over workers, consumers or local citizens, such actions are of critical concern. Micro-economics has long studied and debated such issues, mainly under the headings of market and economic power, externalities, distributional impacts and the social choice of allocation systems. Micro-economics also offers a necessary and stimulating framework within which some of the moral questions at stake can be discussed and within which the practical problems of reforming existing organisations – and perhaps developing socially desirable new ones – can be clarified. These wider social issues cannot be lost sight of, even if space forbids more than a brief mention of them.

![]()

Chapter 2

Markets, Bureaucracies, Gifts

As mentioned in the last chapter, allocation systems represent a way of looking at bigger social systems. An allocation system is the method by which any sort of social system, be it a family, tribe, municipality or business, obtains, produces and distributes resources. But there is no simple way to sum up the allocation systems used by any organisation, however small. Even the systems employed by a tiny shop round the corner cannot be contained within the simple market concepts of ‘buying’ and ‘selling’. Still less can the allocative processes of vast businesses like ITT or ICI be wholly subsumed under the label of ‘markets’. Nor can the expenditure decisions of, say, the Greater London Council be neatly encapsulated in the conventional categories of citizen choice exercised through the ballot box. On the contrary, a given type of social system, whatever its size and sector, has to employ several types of allocation system in deploying resources. Moreover, these allocation systems interrelate in complex ways.

In this chapter we outline a classification of allocation systems which emphasises the interconnections, overlaps and contrasts between business, public and voluntary organisations. We glance briefly at some stimulating contemporary economic ideas about the interplay – in and around such organisations – of allocation systems based on power, self-interested exchange and social benevolence. These ideas help to illuminate the scene within which organisational decision making, to be discussed in the following few chapters, is set. The ideas are reviewed in broad outline: a note on further reading, with a list of their main expositors, will be found at the end of the chapter.

CLASSIFYING ALLOCATION SYSTEMS

A very useful framework for considering complex allocation systems has been suggested by the distinguished American economist Kenneth Boulding.1 Boulding suggests that in any society there are basically three methods of organising human activity. One ‘social organiser’ is coercion, using threats and fear. This corresponds to someone saying, in effect, ‘You do this because I tell you or else…’ The second social organiser, which Boulding calls ‘integration’, relies on love, loyalty or goodwill, and corresponds to someone saying, ‘I do this with you or for you because I want to’. And, according to Boulding, the third organiser is based on exchange, implying a contractual or conditional relationship, namely, ‘If you do this for me, but only if, then I will do that for you’. As Boulding remarks, these are polarisations and, at least in their purer forms, rare. But essentially his argument is that in any social system the three organising principles of coercion, integration and exchange are all present, although in widely varying mixtures and forms. For example, even in the family, where integration and affection play such a big role, coercion is also found. In business life, where exchange relationships are most highly developed, both coercion and integration are also evident. In government, as Boulding suggests, the mixture is particularly rich. Thus people obey governments partly because they fear punishment if they don't (coercion), partly because they identify with governments and their aims as a result of altruism, patriotism or public spirit (integration), and partly also because they see that in return for taxes and obedience to laws, government after all provides things they need and desire (exchange).

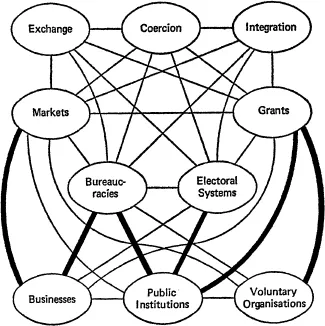

Figure 1 Interacting allocation systems

This three-angled perspective on allocation systems will recur several times in this book. The accompanying diagram (Figure 1) extends the Boulding framework downwards into the areas we are concerned with. Just below the Boulding triad itself are the two main allocative systems characteristic of developed societies, namely markets (whereby goods and services are exchanged for money) and grants (whereby goods and services are transferred in one-way fashion from some people to others, by families, private gift making or government). However, in complex societies, neither markets nor grants can operate without intricate support and control systems. Bureaucracies, i.e. administrative and hierarchical systems of officials, are essential. Economists as well as sociologists and political scientists have found that bureaucracies tend to develop a life of their own and to exert a strong and distinctive influence on the allocation of resources, whether in business, government or even in the voluntary sector. So bureaucracies represent another form of allocative system, whether or not this is explicitly recognised. So, too, in political democracies, do systems of electoral choice. The economic implications of different types of election systems, and particularly of majority voting, have been considerably discussed by modern economists. However great the gap between democratic theory and practice, however crude the operation of choice through the ballot box and however great or small its final effects, the voting system represents yet another way of influencing the allocation of resources.

The bottom tier of the diagram shows the three types of organisation we are concerned with, namely businesses, public institutions and voluntary organisations. The lines connecting all of these elements symbolise interactions or mutual influences between them. The heavy lines represent the more obvious primary links. Thus businesses primarily operate through markets and bureaucracies; public institutions through elective systems, bureaucracies and grants; voluntary organisations through grants and, sometimes, bureaucracies. However, the three types of organisation have some links with all types of allocation system. For example, businesses both receive grants (mainly from government) and make them; local authorities dep...