![]()

PART I

Silent Westerns

![]()

1

The Earliest Western Films

Daryl E. Jones

Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery, produced in 1903 by the Edison Company, is commonly acknowledged to be the first Western motion picture, for it was the first film to employ within a fully realized dramatic framework the characters, incidents, and settings typical of the later Western. Less widely known are the considerable number of prototype Western films produced before the turn of the century. These films, all Edison Company productions, utilized Western material and, in two cases at least, incorporated the rudiments of drama. The films are certainly interesting enough in their own right as technological artifacts of the dawn of the motion picture industry. Yet they accrue additional historical and cultural significance insofar as they anticipate the development of the feature-length Western film, and thus represent an important pioneering phase in the evolution of the genre.

Although by the closing decades of the nineteenth century the Western story was a firmly established and enormously successful form of popular literature, the Western film as a clearly defined form was comparatively slow in emerging. Film historian William K. Everson attributes this delay to two major factors. First, until film production began on the West Coast in 1910, the majority of Westerns were produced on the East Coast, where even the wildest settings lacked authentic western flavor, and where genuine cowboys and authentic costumes were unavailable. Second, these early Westerns lacked a recognizable hero endowed with youth, color, charisma, and manifest virtue, the traits which would later come to characterize the screen image of the Western hero. Not until the frequent appearances of G. M. “Broncho Billy” Anderson in 1907–1909 did such a concept of the Western hero develop.1

The absence of a recognizable hero is ironic in that motion pictures, almost at the moment of their inception, had formed a connection with the most glamorous Western hero of the age, yet did not make the fullest possible use of him. During the season of 1893–94, while Edison was producing peep-show pictures for use in the Kinetoscope, he brought to “The Black Maria,” his West Orange, New Jersey studio, an odd assortment of vaudeville acts and popular entertainers of the day. Among the many acts which performed before the camera that season were Professor Batty’s troupe of trained bears, Mme. Bertholdi the contortionist, strong man Eugene Sandow, and a well-known dentist by the name of Colton who demonstrated a tooth extraction. Preeminent even among such notables, however, were Buffalo Bill and his company. In addition to the famous Colonel Cody himself, Edison photographed Annie Oakley, known as “Little Sure Shot” of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, and a group of Sioux Indian dancers. All of the resulting films were fifty feet or less in length, and were purely documentary.2 Although Buffalo Bill was even then too old to become a Western matinee idol, the idea apparently never occurred to Edison to make any use whatsoever of Cody in a dramatic role. It was not, in fact, until 1913 that Cody formed, in association with the Essanay Company of Chicago, the Colonel Wm. F. Cody (Buffalo Bill) Historical Picture Company, and commenced acting in a film spectacular based on his exploits in the Indian wars.3

Between 1894 and 1899, however, Edison did produce a considerable number of documentary Western films. Devoid of genuine dramatic content, they nevertheless introduced authentic Western characters, incidents, or settings. Two of the films which survive are specifically identified as Parade of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show (Nos. 1 and 2); a third film depicts an unidentified Procession of Mounted Indians and Cowboys. Indians, especially Indians performing ceremonial dances, are the subject of seven surviving films: Eagle Dance, Pueblo Indians; Buck Dance; Indian Day School [Isleta, New Mexico]; Serving Rations to the Indians (Nos. 1 and 2); Wand Dance, Pueblo Indians; and Circle Dance. Five other films document cowboys at work: Branding Cattle; Calf Branding; Cattle Leaving the Corral; Cattle Fording Stream; and Lassoing Steer. And finally, three surviving films record scenic attractions in the Far West: Royal Gorge [Colorado]; Coaches Going to Cinnabar from Yellowstone Park; and Lower Falls, Grand Canyon, Yellowstone Park.4 These latter films, insofar as they introduce the authentic Western locale missing from films produced on the East Coast, must be considered noteworthy productions in the overall evolution of the Western film.

A more significant advance toward the Western film as we know it today occurred in the fall of 1898, when Tom Crahan, a genuine westerner from Montana, arrived at Edison’s New Jersey establishment. On behalf of the Northwest Transportation Company, which ran a line of boats between Puget Sound and Alaska, Crahan contracted with Edison for motion pictures of Alaska to be used for promotional purposes at the Paris Exposition in 1900. Specifically, Crahan wanted pictures of the Gold Rush–pictures, that is, of the ports, trails, and tent towns of the gold miners and prospectors–and he was willing to pay five dollars a foot for the negative for a total of eight thousand feet of film. Robert Bonine of the Edison staff went west, shot the pictures, and returned to West Orange to develop them.5

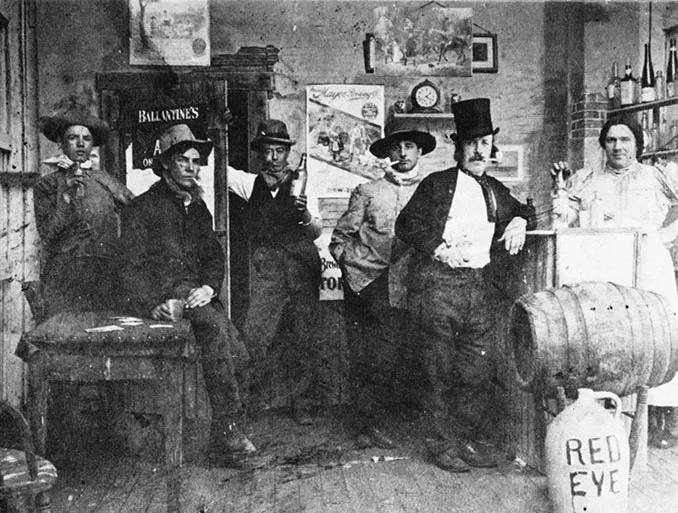

FIGURE 1.1 Cripple Creek Bar-room Scene

Bonine’s films can scarcely be considered Westerns, but they are related to the production of a more significant film, Poker at Dawson City [Alaska Gold Rush]. The speed of this film indicates that it was made in the Black Maria; probably produced in the fall of 1898, the film was perhaps intended to supplement Bonine’s Gold Rush footage. At any rate, the film incorporates an element of character interaction and plot. The action begins with four people seated around a table made by placing a flat board on top of a barrel. They are playing cards and cheating, and eventually a fight ensues. Although nominally dealing with the Alaska Gold Rush, the film is linked specifically to Alaska only through its title; in character, incident, and dramatic content, the film has at least a minimal claim to distinction as perhaps the earliest Western.

This distinction must be shared, however, with another Edison Company film made sometime in the fall of 1898. Produced by Edison’s assistant W. K. L. Dickson, Cripple Creek Bar-room Scene takes place in what is apparently the back room of a shed that has been converted into a bar. A Ballantine’s advertisement hangs on the door and such words as “Redeye” and “Corn Liquor” have been painted on large jugs located around the room. The action begins with a barmaid serving the actors, who soon become intoxicated. The barmaid then opens the door and throws them out. Set in Colorado and incorporating at least minimal dramatic action, Cripple Creek Bar-room Scene is, according to William K. Everson, “by locale if not by content, the movies’ first western.”6 And though Edison produced several other Westerns between 1900 and 1903, all were purely documentary; none measurably advanced the art of the Western film or surpassed the high-water mark attained in this Colorado barroom vignette–none, that is, until The Great Train Robbery appeared in 1903.

Notes

1 William K. Everson, American Silent Film (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978), pp. 238–241.

2 Terry Ramsaye, A Million and One Nights: A History of the Motion Picture (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1926), I, 83.

3 Kevin Brownlow, The War, the West, and the Wilderness (New York: Knopf, 1979), pp. 224–235.

4 All films mentioned by title in this article are indexed in Kemp Niver, Motion Pictures from the Library of Congress Paper Print Collection, 1894–1912 (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1967).

5 Ramsaye, II, 401.

6 Everson, American Silent Film, p. 367. See also George N. Fenin and William K. Everson, The Western: From Silents to the Seventies, 2nd ed., rev. (1962; New York: Penguin, 1977), pp. 47–48.

A CHECKLIST OF PRE-1900 PROTOTYPE WESTERN FILMS IN THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS PAPER PRINT COLLECTION

Of the many films which Edison produced before the turn of the century, only a relative few survive. For copyright purposes, Edison deposited with the Library of Congress the paper-positive prints of a number of his early productions. These primitive films, reprinted by Kemp Niver onto modern emulsions, are preserved in the Library of Congress paper print collection, and are available for viewing. The authoritative index to the 3000 or so titles housed in the collection is Mr. Niver’s Motion Pictures from the Library of Congress Paper Print Collection, 1894–1912 (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1967). An invaluable reference tool, this work indexes films according to general categories such as Comedy, Drama, Newsreels, etc. Unfortunately, however, there is no category devoted exclusively to films which might be considered prototype Westerns; hence students of the early Western film will find their use of the index hampered.

The following checklist, then, cites all Library of Congress paper print collection films which were copyrighted before 1900 and which, through their use of characters, subject matter, or settings indigenous to the American West, have some claim to the broad denomination “Western.” The checklist does not include all pre-1900 Westerns; many films produced before 1900 were never copyrighted, and therefore prints of them do not exist in the Library of Congress. Furthermore, since many copyright prints were filed some time after their production, the production and copyright dates cannot be considered coincident.

The form of the checklist entries conforms to that employed by Mr. Niver, with the exception that page numbers have been added as cross-references to Mr. Niver’s index. The films are listed according to date of copyright and copyright number. The condition of the films, if not specified, is good.

BRANDING CATTLE (p. 129)

Producer: Edison. Copyright: 13529, 24 Feb 1898. 16mm Footage: 62. Condition: Poor.

In the foreground, four men brand a white steer. They hold the animal by its horns, a back leg, and their lassos. The poor condition of the film prevents further description.

CALF BRANDING (p. 130)

Producer: Edison. Copyright: 13531, 24 Feb 1898. 16mm Footage: 62.

The camera is positioned near a fire being used to heat branding irons. The film begins as three men go through the various operations of branding cattle. A large herd of cattle is visible in the background.

EAGLE DANCE, PUEBLO INDIANS (pp. 134, 285)

Producer: Edison. Copyright: 13541, 24 Feb 1898. 16mm Footage: 27.

An Indian chief in a full-feathered war bonnet executes a step-and-a-half dance while a group of approximately twenty other Indians watches. Two tents are visible in the background.

CATTLE LEAVING THE CORRAL (p. 131)

Producer: Edison. Copyright: 13542, 24 Feb 1898. 16mm Footage: 25. Condition: Fair.

The film shows a gate to a corral, two men on the fence-post above the gate, and a herd of cattle behind the gate. The gate opens, and four men on horseback herd the cattle through the gate, leaving the corral empty.

CATTLE FORDING STREAM (p. 280)

Producer: Edison. Copyright: 13549, 24 Feb 1898. 16mm Footage: 64.

Three men and a boy, all mounted on horseback, drive a herd of cattle across a small river and toward the camera.

PROCESSION OF MOUNTED INDIANS AND COWBOYS (p. 306)

Producer: Edison. Copyright: 13550, 24 Feb 1898. 16mm Footage: 63. Condition: Fair.

The camera is positioned above the heads of spectators watching a parade similar to a wild west show. The film shows floats, decorated wagons, etc.

BUCK DANCE (p. 129)

Producer: Edison. Copyright: 13556, 24 Feb 1898. 16mm Footage: 32.

The film shows a group of Indians seated on the ground in a circle around some male dancers. Tents are also visible.

INDIAN DAY SCHOOL [ISLETA, NEW MEXICO] (p. 141)

Producer: Edison. Copyright: 13560, 24 Feb 1898. 16mm Footage: 30.

The film shows the doorway of a building with a sign in front indicating that the building is the Isleta Indian School. Children under ten years of age emerge from the door and pass before the camera.

SERVING RATIONS TO THE INDIANS, NO. 1 (p. 156)

Producer: Edison. Copyright: 13561, 24 Feb 1898. 16mm Footage: 27. Condition: Fair.

The film opens with a view of what appears to be a government log cabin. Indians carrying flour or grain sacks emerge from the door.

SERVING RATIONS TO THE INDIANS, NO. 2 (p. 157)

Producer: Edison. Copyright: 13562, 24 Feb 1898. 16mm Footage: 19.

The film shows a log building with two doors facing the camera. Indians carrying supplies emerge from the building and walk toward the camera.

WAND DANCE, PUEBLO INDIANS (p. 163)

Producer: Edison. Copyright: 13563, 24 Feb 1898. 16mm Footage: 27. Condition: Fair.

A group of Pueblo Indians, some with and some without headdress, dance in a circle around a man beating a drum. Each dancer brandishes a stick or wand.

ROYAL GORGE [COLORADO] (p. 308)

Producer: Edison. Copyright: 13565, 24 Feb 1898. 16mm Footage: 21. Condition: Fair.

The camera is positioned on the rear part of a train winding along a triple track through mountainous country. The film shows a panoramic view of the rugged surrounding scenery.

CIRCLE DANCE (p. 282)

Producer: Edison. Copyright: 13566, 24 Feb 1898. 16mm Footage: 20. Condition: Fair.

Approximately fifty male Indian dancers stand shoulder-to-shoulder in a circle with their backs to the camera. The circle of men revolves slowly as several spectators watch. Two tepees are also visible. Halfway through the film, the following words appear st...