![]()

Contemporary Writing Systems

![]()

Arabic

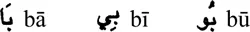

Arabic is written from right to left in an alphabet of twenty-eight letters, all of which represent consonants – and therefore it can more rightly be called an abjad. The written language indicates six vowels, three short and three long. The three short vowels are fatḥa (a), kasra (i) and ḍamma (u). Fatḥa and ḍamma are written above, and kasra below the line, to indicate that the vowel follows the consonant to which it is affixed. Thus, with the consonant /b/:

The short vowel symbols are not normally written except in pedagogical texts, and of course in the Qur’ān, texts of which are always fully vocalized.

The three consonants alif, wāw and yā’ are used in the notation of the three long vowels, usually transcribed into Roman as ā, ī, ū, with their short counterparts, fatḥa, kasra and ḍamma, on the preceding consonant: thus, again with /b/:

Twenty-two of the letters are connected in writing both to the preceding and to the following letter; the relevant initial, medial and final forms are set out in the accompanying table. It will be seen, however, that six letters have no medial form: that is, they cannot be joined to a following letter.

Additional signs used in Arabic script:

(a)

Nunation. An Arabic noun is either definite or indefinite. For most nouns, indefiniteness is expressed by nunation; that is, the addition of the ending /-

un/, marked as

superscript (in the nominative; the marker changes to

/-

an/ and

/-

in/ in the oblique cases). For example:

(b)

Sukūn. The superscript marker over a consonant indicates that that consonant is vowelless; for example,

‘East’, where

rā’ is marked by

sukūn.

(c)

Hamza. The marker

indicates the glottal stop. The bearer for initial

hamza is always

alif, with

fatâ

a,

kasra or à

amma as required. Medially,

hamza may be carried by

alif,

wāw or

yā’; finally, it is placed on the line of script.

(d)

Shadda. A doubled consonant (geminate) is written as a single consonant with the sign

over it. This is called

shadda or

tashdid. Examples:

(e)

Madda. If long

alif follows the glottal stop, the

hamza sign is dropped, and one

alif is written as superscript over a second:

= /

’a:/.

Madda may occur medially, notably in the word

qur’ānun ‘Qur’ān’, ‘Koran’. Arabic has no capital letters.

The Arabic script is a derivative of the Nabataean consonantal script, which was used for inscriptions in Petra from the second century BC to the second century AD. The earliest manuscripts of the Qur’ān (eighth to tenth century) are written in a style known as Kufic, associated with the city of Kūfah in Mesopotamia, though this provenance has been questioned. It is the source of the maghribī style, which developed in Spain and which is still used in the Arab states of North Africa.

From the eleventh century onwards, the beautiful flowing cursive style known as the naskhī was developed and perfected to become the Arabic script par excellence. This is the form which underlies most contemporary type-fonts. A somewhat simplified form, known as ruq’a, has been used for ordinary purposes of handwriting (as distinct from calligraphy) since the Ottoman period. This utilitarian form does not, however, depart from naskhī in the way that ‘grass script’ (căo shū), for example, distorts Chinese standard characters.

There are several offshoots of naskhī, such as the ornate and exquisite ta’līq (or nasta’liq), much used for poetry in Persian and Urdu, and dīvānī, the script of the Ottoman Turkish imperial chancellery. The supreme tour de force of the dīvānī style is the tuğra – the monogram or cipher specifically designed for each Sultan. Nowhere is the curious alchemy of the Arabic script made more manifest than in the tuğra; the jinn of pure formal beauty emerges from the bottle of the script.

The Arabic script is, or has been, used to notate many other languages. Among those which have abandoned Arabic script for Roman are Indonesian (Malay), Hausa, Somali, Sundanese, Swahili and Turkish. Several Caucasian languages, such as Chechen, Kabardian, Lak, Avar and Lezgi, used the Arabic script until, after a short period of experimental romanization, Cyrillic was imposed upon them. At present, Arabic is retained for a number of important languages, including Persian, Urdu, Pashto, Baluchi, Kurdish, Lahndā, Sindhi and Uighur. Since the phonological inventories of these languages differ, in some cases markedly, from that of Arabic,...