![]()

Framing Family: An Introduction

Jody Koenig Kellas

Department of Communication Studies, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

“Mommy, will you tell me a story about when I was a baby?” “Mommy will you tell me a story about when you and Daddy got married?” “Mommy, will you tell me a story about when you were a kid?” Family communication scholars interested in narratives and storytelling might be able to appreciate the string of questions that have filled many car rides to and from day care, the grocery store, friends’ houses, and school since my daughter was three years old. She is now almost six, but is still fascinated by our family stories. She likes to hear the same ones over and over, and she likes to hear me tell them, excitedly anticipating funny moments and climaxes and correcting me if I miss an important detail. According to McAdams (1993), we develop personal myths from infancy, learning early on, particularly from parents, attitudes about optimism and pessimism, hope, and despair. Like my daughter, “preschool children collect the central images that someday will animate their personal myth…. While much of [the] early imagery passes into oblivion as children grow up, some significant images and representations survive into adulthood and are incorporated into the personal myth” (McAdams, pp. 35–36). In her foundational work on family stories, Elizabeth Stone (1988) echoes the lasting imprint that family stories leave on their members, instilling in us a sense of right and wrong, duty, understanding of family, and how to behave in the world. In short, family stories shape, and are shaped by, its members.

I began conducting research on family stories and storytelling long before I was married and became a parent, unaware of the ways in which they would impact my children, my own parenting, and our sense of building family history. Yet, research consistently demonstrates that stories and storytelling are one of the primary ways that families and family members make sense of everyday, as well as difficult, events, create a sense of individual and group identity, remember, connect generations, and establish guidelines for family behavior. Indeed, research on stories and storytelling in the family has steadily increased over the last few decades. This research suggests that family stories and storytelling are central to creating, maintaining, understanding, and communicating personal relationships. Yet, empirical research on family storytelling within the field of family communication is still in its early stages of development and thus ripe for additional research.

In this area of study, scholarship specifically focused on narrative as a communication process has explored the content of stories told between family members or about families (e.g., Vangelisti, Crumley, & Baker, 1999), the interaction processes involved in collaborative family storytelling (e.g., Koenig Kellas, 2005; Trees & Koenig Kellas, 2009), the ways in which family stories are innovated, interpreted, and shared across generations (e.g., Langellier & Peterson, 2004), as well as the ways in which family stories and storytelling can both confirm and reject individual and family identity (e.g., Langellier & Peterson, 1993), to name a few. Some research in this area also has revealed a variety of constructs associated with such communication processes, including family satisfaction (e.g., Trees & Koenig Kellas, 2009), family functioning (e.g., Koenig Kellas, 2005), and relational well-being (e.g., Flora & Segrin, 2003). Because the telling of family stories is significant both within and outside the family, additional research is needed to explore the communication of stories and answer Maines’ (1993) call for situating narrative first and foremost as a communication phenomenon.

With this in mind, I set forth the following purposes in the call for a special issue of the Journal of Family Communication on family storytelling: (1) to highlight research that focuses on family narratives as communicative (e.g., storytelling); (2) to provide insight into the processes, functions, and consequences of family storytelling; and, (3) to explore the contributions that research on family storytelling from different paradigms make to our understanding of the family. In total, I received 15 submissions, each of which underwent blind review by experts in family communication and/or narrative. My sincere gratitude goes to the authors who submitted their work and the reviewers who provided insightful and valuable feedback in record time. The reviewers are acknowledged at the end of this volume. Through this process, I learned much and developed additional curiosity about the processes, content, and functions of family storytelling. The special issue was published in 2010, and in 2011 Routledge/Taylor & Francis invited me to propose the special issue as a book. I enthusiastically agreed based on the benefit I see in increasing readership of and exposure to scholarship that positions communication at the heart of understanding family stories and storytelling.

Drawing inspiration from the original special issue and a recent chapter written for the Handbook of Family Communication (Koenig Kellas & Trees, 2013) on the functions of family storytelling, I have reorganized the order of the articles in the current volume, grouped them under the functions that help to unite and animate them, revised the introduction accordingly, and added two articles – one that originally appeared in the Journal of Family Communication in 2010 (Koenig Kellas, Trees, Schrodt, LeClair-Underberg, & Willer) and one that was invited for this book (Kranstuber Horstman, Chapter 4). Thus, in addition to the revised introduction, the current volume includes six data-based articles that explore the overlapping functions of creating identity in the family, teaching lessons, and making sense of and coping with difficulty. Per the vision of the original special issue, this volume includes a variety of epistemological approaches to inquiry on family stories and thus illuminates the strengths that different paradigmatic approaches bring to our understanding of narratives and storytelling in the family. A focus on functions and paradigms alone, however, oversimplifies the complexity of understanding the communication of family stories. Thus, in what follows, I offer grounding for studying family stories as well as a discussion of the many lenses that might orient our attention to the foci relevant to fully understanding family storytelling as communication in previous, current, and future research.

TELLING OUR STORY: STORYTELLING AND FAMILY COMMUNICATION SCHOLARSHIP

As I have argued elsewhere (Koenig Kellas, 2008; Koenig Kellas, Willer, & Kranstuber Horstman, 2010), storytelling deserves the attention of additional (family) communication scholarship for a few reasons. First, storytelling is the manifestation of stories, narratives, and accounts (Koenig Kellas et al., 2010). Thus, as experts in communication processes, communication scholars should attend to the interactive components of telling our family stories. Others have similarly called for the need to center narrative research in communication (e.g., Maines, 1993) and, in addition to the communication scholars cited above, many outside the field of family communication have attended to aspects of marital and family storytelling (e.g., Buehlman, Gottman, & Katz, 1992; Fiese & Marjinsky, 1999; Holmberg, Orbuch, & Veroff, 2004; Veroff, Sutherland, Chadiha, & Ortega, 1993). In their theory of account-making, for example, Harvey and Fine (2006) argue that the interaction of close others (e.g., family members) is essential to the process of sense-making through storytelling. In particular, they concentrate on making sense of loss, arguing that:

When major loss occurs, both persons in a confiding situation may be telling stories of loss and comforting one another. People usually take turns discussing perceptions of what is happening, sometimes asking for input, sometimes asking the other person if he or she sees matters the same way, and sometimes asking if he or she has had similar experiences. It is the reciprocal communicative act that makes this experience a powerfully social event. (p.189, emphasis added)

Second, the process of telling stories, or the way we tell our stories to each other, affects and reflects family. For example, through their narrative performance theory, Langellier and Peterson (2004, 2006) have contributed much to our understanding of how “storytelling is one way of doing family” (2006, p. 100). In other words, storytelling not only helps us make sense of family experiences, but also performs, creates, and shapes family relationships as well as individual and cultural identities. Moreover, how we tell stories and how we communicate during storytelling interactions is consistently linked with other variables that reflect family culture (e.g., marital and family satisfaction, Trees & Koenig Kellas, 2009; Veroff, Sutherland et al., 1993; and family functioning, Fiese & Marjinsky, 1999).

Third, storytelling is a ubiquitous part of communicated family life. Families tell stories to socialize members (e.g., Miller, Sandel, Liang, & Fung, 2001; Stone, 2004), to cope with difficulty (e.g., Fiese & Wamboldt, 2003; Trees & Koenig Kellas, 2009), to create and reinforce family identity (e.g., Bohanek, Marin, Fivush, & Duke, 2006), to recount the events of the day, to make others laugh, to bridge long-distance relationships, and even to kill time. Despite the fact that it pervades family life, everyday storytelling in the family is understudied. Although seemingly mundane, an analysis of everyday talk offers an important window into family life and over time paints an aggregate picture of family culture, identity, and meaning-making (Duck, 1994; Wood & Duck, 2006). (Extra)ordinary views into family life through storytelling is colored by a number of potential overlapping lenses or dimensions of interaction, context, and method. A fuller understanding of those lenses provides valuable insight into what we know about family storytelling, what the current articles tell us about family, and what we may fruitfully focus on in the future.

LENSES INTO THE FAMILY: DIMENSIONS OF FAMILY STORYTELLING

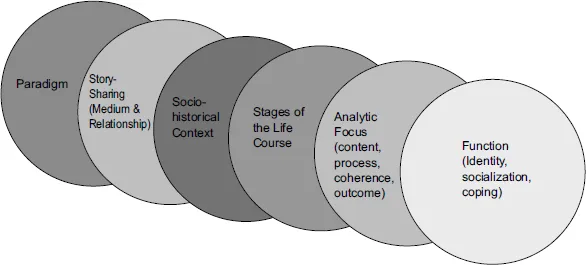

The kinds of questions we ask and what we can know about family storytelling depends on a number of factors that deserve our empirical and theoretical attention including the family developmental life cycle (Pratt & Fiese, 2004), sociohistorical time, context, and culture (Bochner, Ellis, & Tillman-Healy, 1997) and the medium of storysharing (i.e., written, oral, virtual; individual, dyadic, triadic). In our own conceptualizations of storytelling over the last several years, we have also found the parameters of analytic focus (i.e., content, process, outcome, see Koenig Kellas, 2005) and storytelling function (i.e., identity, socialization, coping, see Koenig Kellas & Trees, 2013) as heuristic for understanding the communication of family and relational stories. Each of these aspects relevant to family storytelling may be thought of as a lens through which to view and/or pull into focus the importance of family narratives and storytelling. As we layer lenses on top of one another, the view of family storytelling becomes more complex by bringing many elements of vision into focus (see Figure 1).

The multiple lenses of focus for understanding family storytelling are useful, heuristic, orientations to an area of study that spans disciplinary, methodological, and paradigmatic chasms and can therefore get a bit blurry. Separately, they provide a look into various aspects of family stories, and together they sharpen the focus of the meaning of storytelling in family life. Indeed, the articles in this volume explore storytelling through several of the lenses displayed in Figure 1.

Although each is important and provides its own prescriptive focus, the lens of function emerges consistently as an orienting schema for understanding family stories (see Galvin, Bylund, & Brommel, 2008; Turner & West, 2002). Understanding function highlights the importance of family storytelling, and helps us focus on the “so what?,” or “aha” potential of research (Kelley, 2008), including the potential applied and translational nature of narrative research for practitioners and families. For example, understanding the power of family stories for constructing meaning about and coping with loss and the benefits of doing so lends insight to communication practices that may have cathartic, therapeutic, and meaning-making value (see Keeley & Yingling, 2007). Elsewhere, we have identified three primary functions of family storytelling: creating (i.e., communicating and reflecting individual, relational, and family identity), socializing (i.e., teaching lessons and/or socializing family members), and coping (i.e., making sense of and dealing with stress, difficulty, and/or loss) (Koenig Kellas & Trees, 2013). Based on the heuristic nature of these functions, I have used them to organize the original and additional articles in the current volume as described below.

FIGURE 1 Lenses through which to view and research family storytelling

But, each of the chapters is also informed by several other lenses relevant to the communication of family stories. Thus in what follows, rather than duplicating my own (Koenig Kellas, 2008; Koenig Kellas & Trees, 2013; Koenig Kellas et al., 2010) or others’ (e.g., Langellier, 1989; Pratt & Fiese, 2004) efforts to provide a comprehensive overview on narrative or family storytelling research, I begin my discussion of lenses by orienting readers to how the articles in the current volume might be situated in and contribute to current and future narrative theorizing and research on the functions of family storytelling. I then discuss the other lenses that I believe are important to a communicative view of family storytelling and further comment on their value by connecting them with previous research and the chapters that follow.

The Lens of Function

Developing Identity in the Family. One of the primary functions of storytelling, generally and in the family, is the construction of individual and relational identity. Families frame who they are through the stories that characterize their interactions, and members learn how they fit into the group by hearing and telling family narratives (Stone, 2004; Thompson et al., 2009). Although the functions of creating, socializing, and coping often overlap, the current volume takes each in turn, beginning with two chapters about creation stories, or stories that help to build family and individual identity. For example, in Chapter 2 Harrigan explores the adoption creation stories mothers in her sample tell their internationally adopted children. According to Harrigan, “Creation stories are told to produce shared family histories and to ‘help members build coherent personal identities’ (Galvin, 2003, p. 241). In an adoptive family, sharing a creation story … may pose challenges for adoptive parents” (p. 24). Communication scholarship is well-positioned to unpack the processes by which families negotiate such challenges. Indeed, Harrigan examines mothers’ concentrated and varied practices of orienting their internationally adopted children to their identity in the family through telling the adoption story. As she illustrates, they do so by engaging effectively in adoption-related communication, conveying positive reinforcement, building familiarity and history, while at the same time preventing unfounded fantasies about the adoption process.

Another canonical family creation story is the story of courtship which serves as a foundational family narrative (Stone, 2004). In Chapter 3, Doohan, Carrère, and Riggs present the findings of a longitudinal observational study in which spouses jointly construct a relational history narrative as elicited by the Oral History Interview (OHI). Their study supports previous research indicating that the way a couple co-constructs their courtship story predicts the future of their marriage. In other words, the couples’ story affects and reflects their relational identity. They add to current knowledge by showing that marital bond, a construct accessed through the telling of a couple’s marital history, is predictive over time of problems that lead couples to cascade into distance and isolation. In doing so, they illustrate the important, but often overlooked ways in which family stories can have both light and dark implications for relational culture (see Koenig Kellas et al., 2010 for a review).

Telling canonical stories like courtship and adoption narratives is at the heart of developing individual and family identity. Creation stories shed light on the values central to the family as they represent the foundations upon which family is built. Moreover, how important life stories are framed has implications for individual (e.g., Kranstuber & Koenig Kellas, 2011; McAdams, 1993) and relational (e.g., Buehlman, Gottman, & Katz, 1992) well-being. Previous research has developed a strong platform for understanding the nature of family identity stories. The current chapters lend further insight into the ways in which these stories are communicated – told to or with others. Because stories are negotiated with listeners (Bavelas, Coates, & Johnson, 2000) or co-tellers (e.g., Mandelbaum, 1987), continued research on the processes and implications of narratively constructing identity in communication with others merits additional attention.

Teaching Lessons in the ...