This is a test

- 480 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The History of Basque

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Basque is the sole survivor of the very ancient languages of Western Europe. This book, written by an internationally renowned specialist in Basque, provides a comprehensive survey of all that is known about the prehistory of the language, including pronunciation, the grammar and the vocabulary. It also provides a long critical evaluation of the search for its relatives, as well as a thumbnail sketch of the language, a summary of its typological features, an external history and an extensive bibliography.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The History of Basque by R. L. Trask in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

1.1 The Basque Language: Territory, Speakers, Dialects

The Basque language (self-designation euskara; dialect variants euskera and eskuara) is spoken today by about 660,000 people (according to the 1991 census) at the western end of the Pyrenees, along the coast of the Bay of Biscay. The Franco-Spanish frontier runs through the middle of the Basque-speaking territory, leaving rather fewer than 80,000 speakers on the French side, and the remaining half million or so on the Spanish side. The Basque-speaking region extends from just outside the cathedral city of Bayonne (Basque Baiona) in the north to the outskirts of the huge industrial port of Bilbao (Basque Bilbo) in the west; these two cities, and the ancient city of Pamplona (Basque Iruñea), all lie just outside the territory, though all three cities contain significant numbers of Basque-speakers. The beautiful resort city of San Sebastian (Basque Donostia) lies squarely in the middle of the region. As a result of emigrations at various times and for various reasons, Basque-speakers are also to be found in the major cities of Spain and France, in Belgium, in England, in the western United States (mostly in Nevada, Idaho and California), in many parts of Latin America and in Australia. The number of these expatriate speakers is not known, but is probably no more than several tens of thousands.

Like other minority languages, Basque is often perceived primarily as a language of the rural countryside, but this is a misconception: as a result of the heavy industrialization of the two principal Basque provinces of Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa, more than half of all Basque-speakers now live in cities and towns. Moreover, since the creation of the Basque Autonomous Region in 1979, Basque has been co-official with Spanish in the three provinces of the Autonomous Region: Bizkaia, Gipuzkoa and Araba. In the autonomous province of Navarre, Basque also has a degree of official standing. In the French Basque Country, the language has no official status.

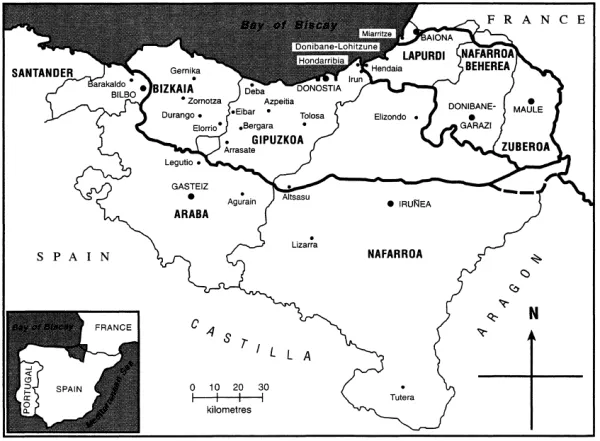

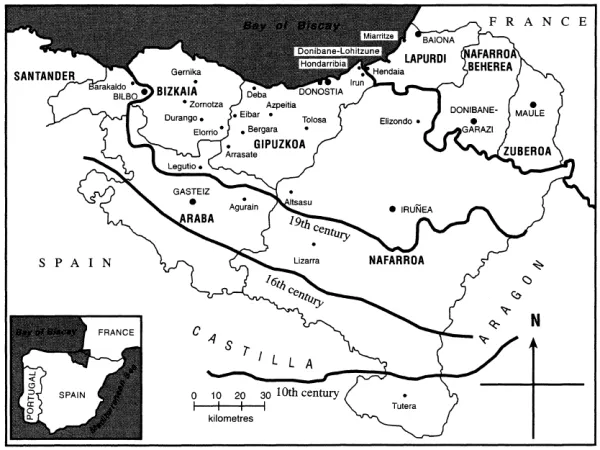

The Basque-speaking territory extends for about 100 miles (160 kilometres) from west to east, and for about 30 miles (50 kilometres) from north to south (see Figure 1.1). The language now occupies less than half of the territory of the Basque Country (Basque Euskal Herria), the region which is historically, ethnically and culturally Basque. Basque-speakers make up about 20 per cent of the roughly 3 million people who live in the Basque Country, more than a million of whom are Spanish immigrants who came to find work in the industrial cities of Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa; few of these immigrants learn Basque. For centuries, Basque has been losing territory to Spanish in the south (see Figure 1.2, which illustrates our best guesses on the basis of the often scanty information available, but note that it is not possible to ascertain the boundaries of the language with precision at any time before the nineteenth century), while the boundary between Basque and Gascon in the north has been largely stable. Apart from small children, probably all Basque-speakers under the age of seventy are now bilingual in Spanish or French, though a number of elderly monoglot speakers remain, particularly in the centre of Gipuzkoa. With the political freedom that followed the death of the Spanish dictator General Franco in 1975, however, there have been determined efforts to reassert the importance of the Basque language in the south, and today, for perhaps the first time in its history, Basque has a sizeable number of speakers who speak it as a second language: euskaldun berriak (literally, ‘new Basques’), as they are called in Basque (the word euskaldun means ‘Basque-speaker’).

Figure 1.1 The extend of the language

Figure 1.2 The recession of the language

The Basque Country is traditionally divided into seven provinces, whose names are given in Table 1.1 both in Basque and in Spanish or French. Nafarroa has a conventional English form Navarre; Bizkaia was formerly known in English as Biscay, but today that name is largely confined to the bay and to the abyssal plain which lies off it. In this book I shall use the Basque forms, except that I shall use ‘Navarre’ for Nafarroa.

Table 1.1 The Basque provinces

Basque form | Spanish/French form |

Bizkaia | Vizcaya |

Gipuzkoa | Guipúzcoa |

Araba | Alava |

Nafarroa | Navarra |

Lapurdi | Labourd |

Nafarroa Beherea | Basse-Navarre |

Zuberoa | Soule |

The four Spanish provinces retain their identity today as provinces of Spain; the first three (Bizkaia, Gipuzkoa, Araba) are united in the Basque Autonomous Region, while Navarre constitutes its own autonomous region. The three French provinces lost their political identity after the French Revolution, when they were merged with the non-Basque region of Béarn in a département originally called Basses-Pyrénées, but now called Pyrénées-Atlantique.

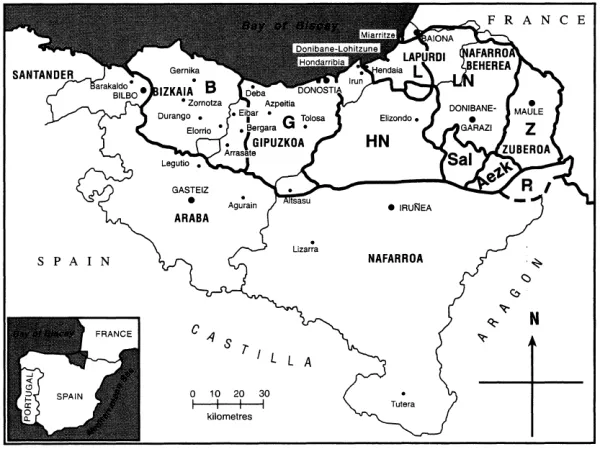

The mountainous terrain of the Basque Country, combined with the longstanding low prestige of the language, has produced some considerable diversification into dialects. This diversification is great enough that speakers from different areas may have significant difficulty in understanding one another if they use their vernacular forms of Basque. None the less, this diversification should not be exaggerated, as has often been done in the literature: the dialects are overwhelmingly congruent in their fundamentals, and differ chiefly in vocabulary and in a few rather low-level phonological rules. There is a popular perception that the Bizkaian dialect in the west of the country is the single most divergent variety, but this perception is not supported by linguistic evidence. In the middle of the nineteenth century, the French linguist L. L. Bonaparte proposed a classification of Basque into eight dialects; half a century later, his system was somewhat reorganized by the Basque linguist R. M. de Azkue into seven dialects; in the 1950s, the Basque linguist Luis Michelena further elaborated the system into nine dialects, and it is Michelena’s classification which I shall follow in this book. These dialects are listed in Table 1.2, while Figure 1.3 shows their conventional boundaries. The Roncalese dialect has for years been on the very brink of extinction, and now appears to be actually extinct. In addition, one other distinctive dialect, long extinct, is attested in a single book compiled in 1562; this dialect, apparently spoken in Araba, is called meridional by Michelena, and I shall call it Southern (Sout). The province of Gipuzkoa has the largest number of Basque-speakers, but, because the speech of much of western Gipuzkoa is classified as Bizkaian, it is probably the Bizkaian dialect which has the most speakers of any dialect.

Table 1.2 The dialects of Basque

Dialect | Abbreviation | Spanish/French form |

Bizkaian | B | Vizcaíno |

Gipuzkoan | G | Guipuzcoano |

High Navarrese | HN | alto-navarro |

Aezkoan | Aezk | Aezcoano |

Salazarese | Sal | salacenco |

Roncalese | R | roncalés |

Lapurdian | L | labourdin |

Low Navarrese | LN | bas-navarrais |

Zuberoan | Z | souletin |

Figure 1.3 The dialects

Speaking very broadly, it appears that the central dialects have been the most innovative and the peripheral dialects the most conservative. But this is no more than a vague impression: at present, our knowledge of the histories of the several dialects is still in its infancy, apart from the phonological history, of which we know a good deal. But it would be a trivial matter to list apparent innovations which are confined either to the eastern varieties or to Bizkaian in the west, and it may be that our vague impression will be substantially altered by further work. In any case, it is often next to impossible to decide whether particular regional features, such as the dative flag -ts- of Bizkaian, or the words ler ‘pine tree’ and aizto ‘knife’ of Roncalese, are archaisms or innovations.

Since the 1960s the Basques have been gradually developing a standard form of the language, called euskara batua, or Unified Basque, under the leadership of Euskaltzaindia, the Royal Basque Language Academy. A standard orthography was promulgated in 1964, followed by a standard morphology, standard forms of all place names, and a basic vocabulary for schools; this standard is largely based on the central dialect of Gipuzkoan, with significant input from Lapurdian and Low Navarrese. More recently, the programme has been continued by others, particularly by the educational organization UZEI, which has published a large number of technical dictionaries, as a result of which it is now possible to write in standard Basque on virtually any subject. Most younger speakers of Basque can now write in batua, and can adjust their speech to batua norms when speaking to people from outside their own area. Neither the pronunciation nor the syntax has yet received any standardization, however, and considerable lexical differences remain, particularly between French Basques and Spanish Basques. A brief history of the standardization of Basque can be found in Rebuschi (1983/1984).

1.2 The Country, the People and their History

The Basque-speaking region is overwhelmingly mountainous: this is a land of limestone mountains, separated by narrow V-shaped valleys, with only the occasional broader valley. In the north there is a narrow coastal plain; elsewhere the mountains run right down to the sea. The seacoast is blessed with several fine natural harbours and with the great estuary of Bilbao, and of course the magnificent sandy beaches of San Sebastian and Biarritz (Basque Miarritze) are world-famous.

Facing as it does onto the Bay of Biscay, the Basque-speaking region is wet. The weather comes from the sea and drenches the country almost throughout the year: the steady drizzle the Basques call zirimiri is a familiar fact of life here. Consequently, the land is green: except where bare mountaintops rise whitely above the tree line, a dark green carpet of deciduous forest covers the hills: beech, birch, ash, oak, with the occasional stand of fir or wild pine. Or at least this used to be so: today a huge area of the Spanish Basque Country has seen its indigenous forest stripped away and replaced by cultivated pine trees grown for timber. Summers are warm rather than hot; winters are mild but very wet, and snow is not common in the valleys. Overall, the climate is reminiscent of that of England.

Very different is the southern half of the Basque Country, the area in which the language has been lost. Much of this region is a high plateau, flatter and drier than the north, hotter in summer and colder in winter. Here the dominant colours are yellow and brown, all the way down to the narrow green ribbon which outlines the course of the Ebro, the great river which marks the southern edge of the Basque Country. The far south is wine country: it forms part of the Rioja, Spain’s most famous wine-producing region. Today you are unlikely to hear a word of Basque spoken in the vineyards, but the names on the bottles are still unmistakably Basque: Ardanza, Olite, Murrieta, Ochoa, Olarra, Amezaga, Arana, Alberdi, Muga, Sarria and many others.

The Basque Country has been more or less continuously inhabited since palaeolithic times, though evidence from the lower palaeolithic period is sparse, and it may be that only the final retreat of the ice around 10,000 years ago allowed the country to become permanently habitable. From the upper palaeolithic period we begin finding extensive testimony of human habitation, the most striking being, of course, the cave art preserved in the region’s numerous limestone caves; the most important of these caves are Otsozelaia (French Oxocelaya) in the French Basque Country, Ekain in Gipuzkoa and Santimamiñe in Bizkaia.

During the neolithic period (roughly 4,000–2,000 BC), the evidence for habitation becomes very much more abundant, possibly because of a steadily improving climate. In this period, pottery and agriculture make their first appearance, as do open-air settlements, though all these are largely confined to the south of the country; again, it may well have been a harsher climate which obliged the mountain dwellers in the north to retain their pastoral economy and their cave dwellings. Only in the Bronze Age (ca. 2000–900 BC) do we begin to find clear evidence of a settled agrarian economy in the mountains. A further striking difference between the two regions consists of megaliths: megalithic structures, and above all dolmens, are common in this period in the mountainous north, but unknown in the south. Archaeologists are divided as to whether this difference represents two distinct populations, with their own economies and cultures, or whether it should be interpreted as indicating a single population practising both agriculture and seasonal transhumance. If the dolmens are interpreted as tombs, it is hard to deny the presence of two distinct cultures, but if, as some have suggested, they were merely seasonal shelters for shepherds, a single population becomes entirely plausible.

On the whole, in spite of the regional differences, archaeologists are satisfied that the record of occupation in the Basque Country from the palaeolithic to the end of the Bronze Age is one of continuity: everything points to the uninterrupted presence of the same people, with their culture evolving in place and receiving influences, but not invasions, from elsewhere in Europe. Consequently, many people have somewhat enthusiastically declared the Basques to be the direct descendants of the original human settlers of Europe, the Cro-Magnon people of some 35,000 years ago. While by no means totally out of the question, such speculations have until recently been supported by little more than negative evidence–the absence of evidence for new populations–and, as we shall see in the next section, they run into difficulty with the linguistic evidence.

On the other hand, the geneticist Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza and his colleagues have recently been constructing a genetic map of Europe, and they conclude that the Basques are, genetically speaking, strikingly different from their neighbours (Cavalli-Sforza 1988; Bertranpetit and Cavalli-Sforza 1991; Cavalli-Sforza et al 1994). These workers find a sharply defined genetic gradient separating the population of the Basque Country from the other inhabitants of the Iberian Peninsula, and a somewhat more diffuse gradient separating them from the other people of France, with the south-west of France showing marked affinities with the Basque Country, an observation which is strongly in harmony with the linguistic evidence discussed below.

Bertranpetit and Cavalli-Sforza (1991) draw the following bold conclusions:

[T]he major difference in the Iberian Peninsula is that between people originally of Basque and non-Basque descent. The recession in time of the boundaries of the Basque-speaking area seems correlated with the progressive genetic dilution of the Basque genotype in modern populations.... Most probably, Basques represent descendants of Paleolithic and/or Mesolithic populations and non-Basques later arrivals, beginning with the Neolithic.

(p. 51)

[Our results suggest] that, in Iberia, the Basques were less changed by subsequent admixture with later arrivals, while in other areas of Mesolithic development, this dilution has largely altered the initial genetic pattern.

(p.60)

The Iron Age (about 900–200 BC) is significantly different: here we find signs of what can plausibly be taken as evidence for invaders, in the form of a small number of fortified settlements quite different from anything seen earlier in the region but rather similar to those associated with the Iron Age culture of the Celts across much of Europe. These settlements persist until the Roman invasion of Spain, and, since we have certain evidence for Celtic-speakers in Spain before the Romans, and (as we shall see) clear evidence for Indo-European-speakers, most likely Celts, in much of the Basque Country, it is not excessively rash to conclude that it was during the Iron Age that the Indo-Europeans moved into the Basque Country.

In the second century BC the Romans began their slow conquest o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- List of abbreviations

- A note on citation forms

- 1. Introduction

- 2. A thumbnail sketch of the language

- 3. Phonology

- 4. Grammar

- 5. Lexicon

- 6. Connections with other languages

- References

- Index