eBook - ePub

The Stationary Economy (Routledge Revivals)

Principles of Political Economy Volume I

This is a test

- 238 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

First published in 1965, this is a reissue of the first volume in Professor Meade's highly influential Principles of Political Economy, which aimed to provide an overview of economic analysis in light of contemporary developments in the subject. This volume is based on models of economic systems in which conditions are such as to make possible a state of perfect competition, in which there are no capital goods, in which consumers' tastes, technical knowledge, and the size and composition of the goods are static.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Stationary Economy (Routledge Revivals) by James E. Meade in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economia & Teoria economica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER XI

FIXED TECHNICAL CO-EFFICIENTS

In the two previous chapters we have discussed the economic system as if it were composed of a number of separate and independent processes within each of which there is the possibility of some marginal adjustments in the pattern of inputs and outputs. There are engineering works and dairy farms; in the engineering works some adjustments can be made in the proportions in which different engineering products are produced and in the proportions in which different factors are employed; in the dairy farms some adjustments can be made between the proportions in which butter and cheese are produced or in which land and labour are employed; but an engineering works remains an engineering works and a dairy farm a dairy farm.

This is in fact a realistic and useful way of regarding the economic system and we shall continue often to employ it in the remaining chapters of this work. It will, however, already be clear to the attentive reader of the last two chapters that the problems involved in expanding one process and contracting another are very similar to those involved in making an adjustment of the inputs and outputs of a given process. In this chapter we shall consider a method of analysis which makes no distinction between adjustments as between processes and adjustments within processes.

The method consists in supposing that no adjustments within processes are possible. Each process consists of a method of production whereby a given amount of each factor is needed to produce a given amount of each output; in any one process some inputs and some outputs may, of course, be zero—the dairy farm produces no steel; the scale of operation of the process may be varied, but in this case every input must be increased by the same percentage and every output will be thereby increased by the same percentage. There are, however, a large number of processes, some of which differ rather slightly from each other. For example, there may be many ‘dairy farm’ processes: one may produce much butter and little cheese with much labour and little land; a second may produce little butter and much cheese with much labour and little land; a third may produce much butter and little cheese with little labour and much land; a fourth may produce little butter and much cheese with little labour and much land; and so on, with a number of intermediate processes. In this model it is not possible, for example, to make a completely smooth and continuous adjustment of the ratio of labour to land used in dairy farming, using within the single dairy farming process gradually less and less men and more and more acres to produce the same output. There are a limited number of distinct dairy-farming processes, one using a higher and fixed ratio of men per acre, a second a lower but fixed ratio of men to an acre, and so on. What in the last two chapters we treated as a continuous substitution of factors within a process now itself becomes a choice between different processes with different but fixed factor intensities. Every process has fixed technical co-efficients, i.e. fixed ratios of inputs to outputs. All adjustment in the production system is a matter of expansion and contraction or introduction and elimination of technically rigid processes. If, however, the number of available processes is sufficiently great and their nature sufficiently varied, the result will be approximately the same. What was, for example, a substitution of land for labour within a process itself becomes a choice between two distinct processes which differ slightly in their factor proportions.

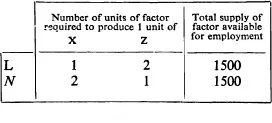

Let us then start with the situation considered in Chapter VIII in which there are only two products X and Z, only two factors L and N, and only two processes one of which uses L and N to produce X and the other of which uses L and N to produce Z. But unlike the situation considered in Chapter VIII we assume now that these two processes are rigid in the sense that in each process the ratio of L to N used is rigidly fixed. Table VI gives a simple numerical example of a situation of this kind. The X-industry is an N-intensive industry requiring 2 units of N and 1 of L to produce 1 unit of X; the Z-industry is L-intensive requiring 1 unit of N and 2 units of L to produce 1 unit of Y. These fixed technical co-efficients together with the available supplies of the factors of production shown in the right-hand column of Table VI can be depicted diagrammatically in Figure 42.

Table VI

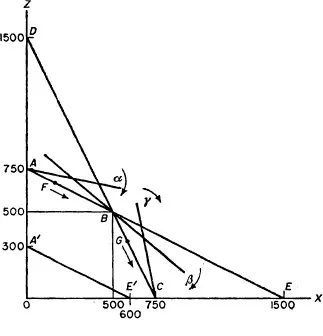

In this figure the line AE shows the combinations of X and Z which could be produced if N were superabundant and production were restrained only by the limited supply of L of 1500 units as shown in Table VI. In this case if all the L were used to produce X, OE or 1500 units of X would be produced; if all the L were used to produce Z, OA or 750 units of Z would be produced; and by moving the labour from X to Z any combination of X and Z on the line AE could be produced. (Cf. p. 85 above.) Similarly if L were super-abundant and production were restrained only by the limited supply of N of 1500 units as shown in Table VI, the line DC would indicate the combinations of X and Z which it were possible to produce. If all the 1500 units of N were used to produce X, OC or 750 units of X would be produced; if all N were used to produce Z, O D or 1500 units of Z would be produced; and, as far as N is concerned, any combination of X and Z on the line DC could be produced.

Figure 42

But in fact neither L nor N are superabundant; the available supplies of both must be taken into account. In fact this means that the production possibility boundary will take the form of the kinked line ABC in Figure 42. The reason for this and the way in which the system will work can best be explained by assuming that all the citizens in the economy start with an extremely strong demand for Z and weak demand for X, that their tastes and needs gradually change so that their demand for Z becomes weaker and weaker and their demand for X stronger and stronger until in the end their demand for Z is very weak and for X is very strong. During this process of shifting demand we will watch in terms of Table VI and Figure 42 what happens to

| (i) | the amounts of X and Z produced, |

| (ii) | the prices of X and Z, |

| (iii) | the amounts of L and N employed, and |

| (iv) | the prices of L and N. |

Suppose then we start with such a heavy demand for Z that only Z is produced. We start at the point A in Figure 42. To produce this 750 units of Z, 1500 units of L and 750 units of N are required. This uses up all the 1500 available units of L but leaves unemployed 750 out of the 1500 available units of N. There is an excess supply of N and the price of N falls to zero in the market. The price of L is such as to absorb the whole of the national income as wages for the suppliers of L.

Although no X is being produced there are nevertheless two prices of X which are relevant to the situation. ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- The Stationary Economy

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Copyright

- PREFACE

- CONTENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- I Ten Assumptions

- II Consumers’ Choice

- III The Market for Consumption Goods

- IV The Terms of Trade

- V Constant Costs

- VI Increasing Costs: (i) Comparative Advantages

- VII Increasing Costs: (ii) A Fixed Factor

- VIII Increasing Costs: (iii) Differences in Factor Proportions

- IX Many Factors and Many Products

- X Changes in Technical Knowledge and in Factor Supplies

- XI Fixed Technical Co-efficients

- XII Economic Efficiency and the Distribution of Income

- XIII The Centrally Planned Economy: (i) The Organization of Consumption

- XIV The Centrally Planned Economy: (ii) The Organization of Production

- XV The Centrally Planned Economy: (iii) The Deployment of Labour—Conclusion

- INDEX