![]()

Real exchange rates and Purchasing Power Parity: mean-reversion in economic thought

Mark P. Taylor

Department of Economics, University of Warwick, Coventry, CV4 7AL, UK

This study provides a critical review of the research literature on long-run Purchasing Power Parity and the stability of real exchange rates.

I. Introduction

During the past three decades – notably since the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates – an ongoing and lively debate has been conducted among international economists concerning purchasing power parity (PPP) and the stability of real exchange rates. Professional confidence in the validity of PPP even as a long-run equilibrium condition has waxed and waned considerably over this period, from a consensus belief in the very early 1970s, to outright rejection in the late 1980s, to guarded confidence in long-run PPP in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Indeed, economic thought in this area might itself be seen to have displayed a measure of the mean reversion that has so often been tested for in real exchange rates.

This study provides a selective overview of this research, with an emphasis on recent developments and contributions.1 It begins, however, with an outline of the conceptual origins of purchasing power parity.

II. Purchasing Power Parity: Conceptual Origins

The concept of PPP and discussions relating to the relationship between the exchange rate and prices more generally have a very long history in economics, dating back as far as the writings of the scholars of the University of Salamanca in the sixteenth century. The development of the concept of purchasing power at this time appears to have been due to the confluence of three major influences. First, the University of Salamanca was at that time one of the world’s leading seats of learning; second, this was the period of Spain’s ‘Great Inflation’; third, the Catholic Church at that time prohibited usury – i.e. the charging of interest on loans.

During the first quarter of the sixteenth century, Spain had begun its spectacular expansion in the Americas, and by mid-century it controlled most of the South American continent, Central America, the peninsula of modern-day Florida and the island of Cuba. This new empire not only conferred power and prestige on Spain, it also conferred enormous wealth. This came partly from treasure looted from the former Aztec and Inca empires of Mexico and Peru respectively, but more importantly from the discovery of rich gold and silver mines in the New World, which the Spanish worked with the slave labour of conquered nations. The main economic effect of the massive influx of precious metals into Spain during the sixteenth century was – predictably to a modern economist – to generate an unprecedented high level of inflation (Spain’s so-called Great Inflation) as well as worsening of the balance of trade. (Because Spain imported goods from the rest of Europe, prices in general rose throughout the continent, although price rises were particularly marked in Spain.) The connection between inflation and the expansion of the money supply – the forerunner of the quantity theory of money – was first traced by the Salamanca scholars (see Lothian, 1997a), although their chief insight was simply to observe the relative shifts in purchasing power between currencies with differing inflation rates (Grice-Hutchison, 1952, 1975). Thus, if a loan was made in, say, French currency and repaid a year later in Spanish currency, it would be perfectly reasonable to expect a larger amount of Spanish currency to be repaid than was the equivalent of the initial French principal amount at the time the loan was made, in order to allow for the fall in purchasing power of the Spanish currency over the year. Thus, interest payments could be disguised as movements in relative purchasing power without contravening the Catholic Church’s anti-usury laws. The concept of Purchasing Power Parity had been born.

Something akin to the concept of purchasing power also appears to be implicit in the writings of the classical economists – for example in Hume’s exposition of the specie-flow mechanism (Hume, 1752) and in the writings of Ricardo (1821) and Wheatley (1807, 1822).2 However, later nineteenth-century writers largely ignored the influence of relative prices on exchange rates (or vice versa), and the idea of PPP largely disappears from both academic and policy debate from the early nineteenth century onward, so that, in the words of Einzig (1967), ‘By 1914, the PPP concept was essentially forgotten.’

It was then resurrected in the interwar period largely as the result of the efforts of the Swedish economist Gustav Cassel, who published a large number of articles and books on the topic in the period following the First World War (e.g. Cassel, 1916, 1918, 1922, 1928a, b) in which he first coined the term ‘purchasing power parity’ (Cassel, 1918). Cassel sought to revive interest in the concept of PPP in the context of the policy debate concerning whether and how the major currencies should return to the Gold Standard which had been suspended during the war, and in the specific context of discussion of the rate at which sterling should return to the Gold Standard. In this, Cassel was successful in converting Keynes to the cause (1923). However, despite Keynes’s influence in British policy circles, the concept of PPP was deemed by both the Chancellor of the Exchequer of the time (Winston Churchill) and the Governor of the Bank of England (Montagu Norman) to be too ‘new-fangled’ and experimental to warrant serious consideration: ‘I am not sure where I would turn for such a calculation,’ Montagu Norman told a House of Commons Committee in 1924, ‘and I am not sure I would trust any such calculation if it were made, because they are very experimental, these calculations, don’t you think?’ (Norman’s evidence to the Chamberlain-Bradbury Committee, 1924; cited in Moggridge, 1972, p. 89). Hence, sterling was simply returned to the Gold Standard in May 1925 at a rate of $4.86 to the pound – its pre-war parity, thus overvaluing the pound by some 10% or more according to Keynes (1925) and to a number of later commentators (e.g. Taylor, 1992).3

With the rise of Keynesian economics after the Second World War, open economy macroeconomic analysis was largely conducted in terms of fixed-price models, so that emphasis on PPP naturally did not achieve hard focus. The PPP concept was, however, a key element of monetarist analysis as it was developed primarily at the University of Chicago in the post-war years (Laidler, 1981) and which achieved its locus classicus in Friedman and Schwartz (1963). Since the mid-1906s, the concept appears to have become absorbed, with varying degrees of strictness, into the way many economists think about international macroeconomics and finance. Thus, some 30 years ago, two leading international economists, Rudiger Dornbusch and Paul Krugman, could write: ‘Under the skin of any international economist lies a deep-seated belief in some variant of the PPP theory of the exchange rate’ (Dornbusch and Krugman, 1976). Twenty years later, another leading international economist, Kenneth Rogoff, could express more or less the same sentiment concerning his professional economist colleagues: ‘most instinctively believe in some variant of purchasing power parity as an anchor for long-run real exchange rates’ (Rogoff, 1996). In fact, however, the two-decade gap in the dating of these quotations was a period during which views on the validity or otherwise of long-run PPP shifted a number of times, as we shall see.

III. Purchasing Power Parity: The Algebra

A central building block of PPP is the law of one price (LOP). The LOP states that once converted to a common currency, the same good should sell for the same price in different countries. In other words, for any good i,

where

Pi is the domestic price for good

i,

is the foreign price for good

i, and

Si is the nominal exchange rate expressed as the domestic price of the foreign currency. This expression states that the same good should have the same price across countries if prices are expressed in terms of the same currency. The LOP implicitly assumes that there is perfect competition, that there are no tariff or other trade barriers, and no transportation costs. In practice, due to some or all of these market frictions applying in the real world, the law cannot hold exactly, even if agents assiduously sought to exploit all profitable arbitrage opportunities.

Absolute PPP can be viewed as a generalization of the law of one price. It postulates that given the same currency, a basket of goods will cost the same in any country. Formally,

where,

Pt and

are the prices of the identical basket of goods in the domestic and foreign countries respectively, and

St is again the nominal exchange rate, or the domestic currency price of foreign currency.

4 Clearly, if the aggregate price indices were based on the same basket of goods with the same arithmetic weights, then

Equation 2 would follow from

Equation 1 exactly. If the baskets are not identical, however, then absolute PPP would follow only as an approximation even if the LOP held exactly (see Sarno and Taylor, 2002a for a more detailed discussion of this issue). Moreover, the various frictions that preclude the LOP from holding exactly in the real world will also preclude absolute PPP holding exactly and continuously.

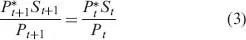

It is easy to see the intuition behind PPP and why in practice it may not appear to hold exactly and continuously. Nevertheless, even in the presence of these obstacles to continuous absolute PPP, one might still expect PPP to hold in relative terms since, despite transport costs and other trade barriers, the change in the exchange rate between two countries’ currencies is likely to be influenced by the change in the price level of one country relative to the other country’s price level. Relative PPP states that the rate of growth in the exchange rate offsets the differential between the rate of growth in home and foreign price indices. Formally, this is represented by,

Thus, if the increase in domestic prices is faster relative to the foreign country then the exchange rate will depreciate proportionately.

One of the major problems with testing PPP is the construction of price indices (should one incorporate traded goods only or both traded and non-traded goods?) and the period of testing (should PPP be tested as a short-run or as a long-run condition?). The difficulty in finding evidence strongly supportive of PPP has provided a strong motivation for researchers to investigate PPP empirically.

IV. Empirical Tests of PPP

Notwithstanding the simplicity and intuitive appeal of PPP, empirical tests have produced mixed verdicts on both its short-run and its long-run validity. To a great extent, economists have tended to find weaknesses with the methodology employed in previous studies that have rejected PPP and have employed new econometric techniques wherever there seemed to be an opportunity of overcoming these problems. The empirical evidence on PPP has in consequence to some extent developed along with advances in econometric techniques.

Early studies

Early studies of PPP are based on simple regression tests of absolute and relative Purchasing Power Parity. Absolute PPP implies that the nominal exchange rate is equal to the ratio of the two relevant national price levels. Relative PPP posits that changes in the exchange rate are equal to changes in relative national prices. Early tests of the absolute form...