![]()

A focused service quality, benefits, overall satisfaction and loyalty model for public aquatic centres

Gary Howat, Gary Crilley and Richard McGrath

Centre for Tourism and Leisure Management, School of Management, University of South Australia, Mawson Lakes Campus, South Australia, Australia

This study supports a parsimonious range of key service quality dimensions that have a strong influence on customer loyalty at public aquatic centres using data from two major centres in Australia (n = 367 and 307). Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) supported a model that included three process services quality dimensions and two benefits (outcomes) dimensions. Using structural equation modelling (SEM), it was found that one of the outcome dimensions (relaxation) and two process dimensions (staffing and facility presentation) significantly influenced overall satisfaction, which mediated significant relationships with three attitudinal loyalty variables. The data from the second centre provided a validation sample to confirm the potential to replicate the model for a different respondent profile. The parsimonious set of dimensions identified in this research could provide a common core suitable for inclusion in service quality research for a range of contexts.

Introduction

In recent years, competition for customers has been increasing due to the number of new or refurbished public and commercial aquatic and fitness centres in many Australian cities (Benton, 2003; Howat et al., 2005a; King, 2004; Whittaker, 2004). Consequently, retention of customers and measuring customer loyalty are increasingly important issues for facility managers. Indicators of customer loyalty include customer service quality as well as customer satisfaction (Bernhardt et al., 2000; Brady and Robertson, 2001; Ganesh et al., 2000; Howat and Crilley, 2007; Philip and Hazlett, 1997; Voss et al., 2004). Linking specific service quality dimensions with loyalty measures allows facility managers to identify strengths and areas for improvement in attributes of the service that they can manage to help improve their competitive advantage.

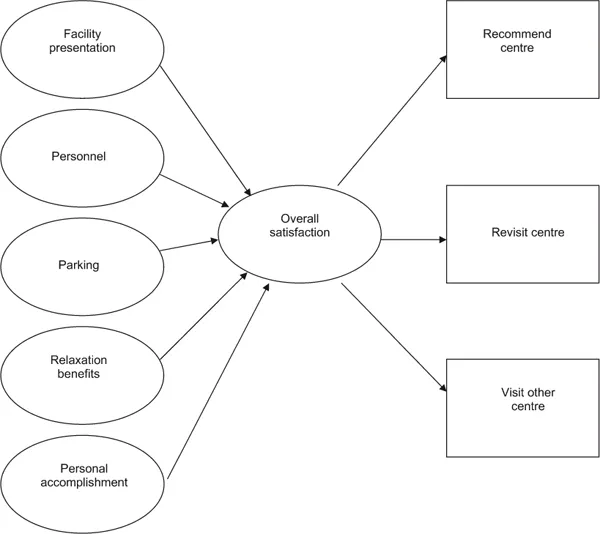

This study examines the relationships between service quality, overall satisfaction and loyalty measures at Australian public aquatic centres (Figure 1). Satisfaction appears to be a combination of emotional and cognitive responses (Oliver, 1997; Wong, 2004; Zeithaml et al., 2006), while service quality, as an antecedent to overall satisfaction, appears to be mainly a customer’s cognitive assessment of a service (Cronin, 2003). Perceptions of service quality affect feelings of satisfaction, which, in turn, influence customers’ likely future support for that service (Alexandris et al., 2004; Bernhardt et al., 2000; Ganesh et al., 2000; Howat et al., 1999; Howat and Murray 2002; Voss et al., 2004).

Fig. 1. A proposed model of the relationships between service quality, overall satisfaction and attitudinal loyalty at public aquatic centres

Customer Loyalty

Customer loyalty is the level of continuity in the customer’s relationship with a brand or service provider (Soderlund, 2006). The behavioural view of loyalty includes repeat purchasing or frequency of attendance (Pritchard et al., 1992) and the duration of the customer–service provider relationship (Soderlund, 2006). The attitudinal view of loyalty includes two major indicators of customer retention – customers’ intention to repurchase, and their willingness to recommend the service to other prospective customers (Rundle-Thiele, 2005; Voss et al., 2004; Zeithaml et al., 2006). ‘Among the most important generic behavioural intentions are willingness to recommend the service to others and repurchase intent’ (Zeithaml et al., 2006: p. 149).

Soderlund (2006), however, asserted that few researchers clearly distinguish between repatronage intentions and word-of-mouth intentions (e.g., Cole and Illum, 2006; Seiders et al., 2005). Word-of-mouth intentions link the customer to other prospective customers, while repatronage intentions relate to a potential future relationship between the customer and the service provider, which may be constrained by such factors as cost and physical access to the service. In contrast, an issue such as physical access may have less influence on willingness to recommend a service to others. For example, self-drive travellers may be willing to recommend a holiday route to other people, but their own repatronage intentions may be relatively low because of the distance from their home location and the costs (time, travel and accommodation) (Howat et al., 2006). Location also had an important influence on levels of visitation with the frequent or ‘heavy users’ of a lunch restaurant being customers whose residence or work place was nearby (Lehtinen and Lehtinen, 1991).

Satisfaction

Satisfaction as an emotional state of mind reflects the benefits (Cole and Illum, 2006) or outcome of an experience (Baker and Crompton, 2000) along with other influences such as process service quality. External issues may also influence the individual’s psychological state and thus the feelings of satisfaction attributed to that experience (Oliver, 1997; Zeithaml et al., 2006). Examples of negative issues include feeling unwell (e.g., due to a cold or tiredness from working long hours) or external factors such as foul weather or unpleasant personal relationships. In contrast, positive life issues, such as a recent promotion or other personal successes, could moderate satisfaction in a positive direction.

Overall satisfaction can be considered as a post-service representation of the customer’s overall feelings toward a service (Choi and Chu, 2001) based on cumulative experiences with that service (Gustafsson et al., 2005; Homburg et al., 2005; Seiders et al., 2005; Skogland and Siguaw, 2004). Oliver (1997) maintained that the aggregated satisfaction episodes from a series of consumption experiences result in ‘overall’ satisfaction, which appears to be one determinant of loyalty. Overall satisfaction, based on the cumulative experiences with the same service provider, is expected to have a stronger relationship with outcome variables (e.g., future purchase behaviour, willingness to recommend) than a single consumption experience (Anderson et al., 1997; Homburg et al., 2005; Jones and Suh, 2000; Olsen and Johnson, 2003; Rust et al., 1995).

However, there is also a caution that industry differences limit the extent to which links between customer satisfaction and behavioural intentions can be extrapolated from one context to another (de Ruyter et al., 1998; Parasuraman et al., 1994). For example, the satisfaction – repurchase intentions relationship appears to be service-specific as concluded from a study of two mid-price hotels in the USA Midwest where there was only a weak link between customer satisfaction and intention to revisit the hotel (Skogland and Siguaw, 2004). Possible explanations include the low cost for customers to switch to alternative service providers. Industries with low switching costs (e.g., amusement parks and fast food) tend to have a weaker service quality–loyalty link than those with higher switching costs (e.g., opera houses) (de Ruyter et al., 1998). Switching costs include extra travel costs, foregoing accrued loyalty benefits, and psychological costs associated with the uncertainty of dealing with different staff or attending a new venue.

The customer–loyalty relationship is much more emphatic for completely satisfied customers compared to those who record lower satisfaction levels (Jones and Sasser, 1995). This is dependent on the competitiveness of the particular market such as the alternative markets available to the customer for that product. And even for markets with little competition, Jones and Sasser (1995) cautioned against assuming that customers display true long-term loyalty compared to false loyalty (spurious loyalty) where customers who are not completely satisfied only remain loyal because they do not have convenient access to alternatives.

Service Quality

A popular conceptualization of service quality involves comparing a customer’s evaluation of the perceived performance of specific attributes of a service to their prior expectations (Parasuraman et al., 1988; Zeithaml et al., 2006). A relatively small number of high priority attributes tend to have a dominant influence on the customers’ perception of a service’s overall quality (Hartline et al., 2003; Howat and Crilley, 2007). For example, expectation ratings indicated the relative importance that respondents gave to service quality attributes in a study of fitness centres (Afthinos et al., 2005). The relatively high importance of the physical attributes of the service (clean, comfortable and modern facilities), and staffing attributes were supported in other research for sports and fitness centres (Papadimitriou and Karteroliotis, 2000) and for public aquatic centres (Howat and Crilley, 2007).

For over two decades, research involving dimensions of service quality has been guided by either the American perspective as represented by the SERVQUAL instrument and its adaptations (Parasuraman et al., 1985, 1988, 1991,1993,1994; Zeithaml et al., 2006) or the European (Nordic) approach (Grönroos 1984, 1993, 2005; Lehtinen and Lehtinen, 1991). The latter includes two broad dimensions of service quality: the technical or outcome dimension and the functional or process dimension.

In the Nordic model technical quality of the outcome is what the customer receives, or ‘… what the customer is left with, when the service production process and its buyer-seller interactions are over’ (Grönroos, 2005: p. 63). Outcomes include the meal received at a restaurant, the room and bed provided by a hotel, the bank loan and transportation for the airline passenger (Grönroos, 2005). However, outcomes that have longer-term impacts, such as health and fitness benefits, tend to be lag indicators that may not yield benefits until some future time (de Bruijn, 2002; Howat et al., 2005b; Robinson and Taylor, 2003). Therefore, such deferred benefits will be more difficult for the customer to evaluate (Asubonteng et al., 1996) as well as to credit directly to a particular service.

Functional quality of the process is how the customer receives the service. The way in which the technical quality or the outcome transfers to the customer involves interactions between the service provider and the customer (relational quality). Additional to relational quality, the functional quality dimension includes physical quality (Grönroos, 2005), where the service is delivered or the ‘servicescape’ (Bitner, 1992). Functional quality attributes, rather than technical quality attributes, are more likely to influence customers’ overall satisfaction with a service, if the customer has a choice of service providers (Grönroos, 1984; Swan and Combs, 1976).

The SERVQUAL instrument categorized service quality attributes into five dimensions (Parasuraman et al., 1988). The first four dimensions were process dimensions that the customer experiences during delivery of the service (how the service is delivered). Tangibles include the ‘… appearance of physical facilities, equipment, personnel, and communication materials’ (Zeithaml et al., 2006: p. 120). Tangible clues (evidence) such as the facility cleanliness and staff appearance help the customer to judge a service before using or purchasing it (Shostack, 1977).

Responsiveness includes employees being willing to assist with custome...