![]()

1 Life-Course Perspectives on Military Service

An Introduction

Janet M. Wilmoth and Andrew S. London

Even before we are born, institutions and social structures begin to shape our lives through their variable effects on our parents and communities. Initially, our families of origin filter the influences of various economic and social forces. As we move through childhood and adolescence, we begin to experience these institutional and structural influences firsthand, through the roles we play as members of our immediate and extended families, as students in educational systems, as worshipers of a given religion, and as patients receiving health care. We arrive on the cusp of adulthood poised to take on new and emergent roles within political institutions, as voting-aged citizens, and within economic institutions, as workers and consumers. As we transition into these and other adult roles, we may experience opportunities related to family connections, higher education, and professional employment, or we may begin to realize the consequences of growing up in disadvantaged circumstances as they play out in constrained educational, employment, and housing opportunities. Some of us will experience spells as inmates in the criminal justice system, while others of us will serve on active duty in the U.S. military.

Life-course scholars have demonstrated that the pathways taken during the demographically dense period of young adulthood (Rindfuss 1991) can leave an indelible mark on the course of human lives. The extant life-course literature demonstrates that these scholars have devoted considerable attention to the influence of family, educational, labor market, and penal institutions on subsequent life-course trajectories and outcomes, including socioeconomic attainment and health. As documented in this volume, a smaller subset of life-course scholars has been concerned with trying to understand the effects of military service on lives.

Glen H. Elder, Jr. is responsible for the most influential early theorizing about the role of military service in the life course (Elder 1986, 1987), and, with a range of colleagues, for empirically demonstrating the importance of military service for life-course studies (Clipp and Elder 1996; Dechter and Elder 2004; Elder and Bailey 1988; Elder and Clipp 1988a,b, 1989; Elder, Gimbel, and Ivie 1991; Elder, Shanahan, and Clipp 1994, 1997; Elder, Wang, Spence, Adkins, and Brown 2010; MacLean and Elder 2007; Pavalko and Elder 1990). As attested by Paul Gade and Brandis Ruise in Chapter 12, as well as in Glen Elders’ foreword to this volume and our own comments below, his influence on the field extends beyond his own direct scholarly contributions to his support of many life-course scholars who have taken up questions related to military service. These scholars and other life-course researchers have contributed to this line of research by examining how the effect of military service varies across individual characteristics, service experiences, historical periods, cohort membership, and the timing of military service in the life course (e.g., Angrist 1990; Angrist and Krueger 1994; Gimbel and Booth 1994, 1996; Teachman 2004, 2005; Teachman and Call 1996; Teachman and Tedrow 2004; Wilmoth, London, and Parker 2010). Taken together, this research provides evidence that the U.S. military is a critical social institution that can (re)shape educational, occupational, income, marital/family, health, and other life-course trajectories and outcomes (London and Wilmoth 2006; Mettler 2005; Modell and Haggerty 1991; Sampson and Laub 1996; Settersten 2006). This body of exemplary life-course research aims, in the words of Modell and Haggerty (1991: 205), “to connect the micro- and macro-levels of analysis, thus connecting the soldier’s story to that of his [or her] changing society.”

Despite the existence of this rich body of research, Settersten and Patterson (2006: 5) have argued that “wartime experiences may be important but largely invisible factors underneath contemporary knowledge about aging” (see also Settersten 2006; Spiro, Schnurr, and Aldwin 1997). We contend that the important institutional influence of military service on lives has more generally been underacknowledged among life-course scholars, and more broadly within Sociology and other disciplines that study human lives, including Demography, Economics, Gerontology, and Psychology. This is ironic given that current knowledge about the life course, in particular, and social life, in general, is substantially derived from research based on cohorts that were born during the 20th century, which featured extended periods of peace punctuated by several periods of war and military conflicts. A substantial percentage of men in current old-age cohorts served in the military during World War II, the Korean War, the Cold War, or some combination thereof. Those men, as well as the women and children whose lives are linked to them, were certainly affected by military service and war. Middle-aged adults, who were born during the middle of the 20th century, experienced the transition from the draft era, which included the Vietnam War, to the early years of the All-Volunteer Force period, which were primarily peaceful. After 1990, young adults as well as those at the beginning of middle age, who were therefore at the prime ages for entering military service, were potentially involved in the Gulf War as well as subsequent conflicts, including Operations Iraqi Freedom, Enduring Freedom, and New Dawn. Importantly, women have increasingly entered the armed forces and directly experienced military service in the most recent decades.

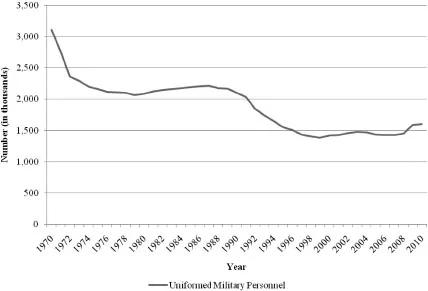

Although rates of participation in the military have declined over the past fifty years as the size of the military has contracted (see Figure 1.1), military service remains a salient pathway to adulthood—particularly for youth from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds (see Bennett and McDonald, Chapter 6 in this volume). The U.S. military remains a primary employer of young and middle-aged adults; in 2010, there were 1,602,000 uniformed military personnel (U.S. Office of Personnel Management 2012). In addition, veterans are a sizeable and policy-relevant demographic group. In 2010, nearly 22 million Americans were veterans, representing approximately 9% of those aged 18 or older (U.S. Census Bureau 2010). The majority (82.5%) of these veterans served during wartime: 9.5% during World War II, 11.8% in the Korean War, 34.9% in the Vietnam War, 15.8% in the Gulf War (8/1990 to 8/2001), and 10.5% in the more recent Gulf War operations (9/2001 or later) (U.S. Census Bureau 2010). Furthermore, as noted above, participation in the military has increased substantially among women; in 2010, nearly 1.6 million American women were veterans (U.S. Census Bureau 2010). However, the extent to which the lives of military personnel and veterans differ from those who have not served in the military has not been systematically documented partly as a result of the dearth of population-level data sources that contain adequate data on military service experiences and allow for explicit comparisons across these groups. Similarly, we know very little about differences in the lives of nonserving citizens who are linked to active-duty service members and veterans versus those who are not.

Figure 1.1 Uniformed military personnel, 1970–2010.

THE LIFE-COURSE PERSPECTIVE: RELEVANT PRINCIPLES, CONCEPTS, AND HYPOTHESES

The rich conceptual and theoretical traditions within the life-course perspective provide fertile ground for empirical research (George 2003, forthcoming; Settersten 1999, 2003), including the role of military service in lives. Although there are ongoing debates regarding the scope of life-course scholarship, including how the life-course concept relates to, and differs from, other concepts, such as life span and life cycle (Alwin 2012a,b; O’Rand and Krecker 1990), there is consensus regarding the importance of five major principles that characterize the life-course perspective: lifelong development, human agency, location in time and place, timing, and linked lives (Elder and Johnson 2002; Elder and Shanahan 2006; Elder et al. 2003). Each of these principles, which are briefly described below, provides a foundation upon which we can begin to understand how military service shapes lives.

First, the principle of lifelong development states that human development and aging must be understood as processes that unfold over time. Given that earlier phases of life shape subsequent stages, studies that focus on a given life stage without taking into account the influence of previous periods are limited. For example, when studying health outcomes among veterans and non-veterans, researchers should consider health during childhood and adolescence and its effect on the ability to pass health screening exams required prior to acceptance into the military, as well as veterans’ exposure to combat and other risks for service-related injuries. This principle highlights the critical importance of having comprehensive data on military service experiences, as well as longitudinal data that enable researchers to address selection and disentangle aging effects from period and cohort effects.

Second, the principle of human agency directs attention to the role that individuals play in their own lives as they actively choose among various opportunities and deal with the constraints that they encounter over the course of their lives. Opportunities and constraints are structured by historical and social circumstances. Consequently, individuals with similar social locations may experience very different opportunities depending on the historical circumstances they face. For example, military personnel who served during World War II and the Korean War and met particular program criteria were eligible for the GI Bill, although access varied by race, regional location, and gender. In contrast, those who served during the post–Korean War period (i.e., the Cold War era) did not have access to the GI Bill until their service was retroactively covered when the GI Bill was reinstated in 1966. Thus, veterans from the Cold War era had fewer opportunities to pursue education upon completion of their military service than prior or most subsequent cohorts.

Third, the principle of location in time and place embeds lives in both a historical period and specific geographic (and increasingly online) locations, where various kinds of people are or are not encountered, certain kinds of interactions do or do not occur, and specific values are or are not emphasized. As we age from childhood through adulthood, the influences of historical events are woven into our quotidian lives through social interactions within the families, friendship networks, communities, organizations, and online environments in which we are embedded. Thus, for example, the experience of the Vietnam War depended in part on whether a person was a young adult living on an urban college campus, a mother of a soldier from rural America, a veteran from World War I or II, or a young man serving in the war zone. Similarly, as D’Ann Campbell (in Chapter 3 of this volume) demonstrates, women’s experiences in the Civil War and World War II were distinctively shaped by historical time and place. Taking into account this nexus of social, historical, and geographic locations requires methodological approaches that include retrospective life histories and multilevel modeling. Even then, the difficulties involved in measuring and modeling time-varying changes in social structures and individual characteristics remains a daunting challenge for the field.

Fourth, the principle of timing focuses on when events and transitions occur in relation to age and other events and transitions. Individuals in different life stages bring various experiences and resources to a given historical event. Consequently, they understand that event and adapt to the new conditions arising from it in different ways. For example, the partner of a commissioned officer who has experienced several tours of duty in Afghanistan is likely to react differently to a deployment than a partner of an enlisted soldier who is being deployed for the first time. This principle also speaks to the importance of when personal life events occur, whether they trigger transitions, and how disruptive they are to ongoing relationships, education, family patterns, and work. Life is characterized by various events that lead to transitions between roles: meeting someone can trigger a transition from being single to partnered; pregnancy can trigger a transition from not being a parent to parenthood; a serious illness can trigger a transition from wellness to a chronic sick role; a war can trigger a transition from civilian status to being a soldier. Sometimes, one event can trigger numerous subsequent, interconnected role transitions that reverberate across the life course; a transition from civilian to soldier during war can lead to a combat role, which can lead to physical or psychological injuries, the emergence of disability, redirection of employment trajectories, the onset of a spousal caregiving role, and marital strain and instability. The consequences of transitions, including their disruptiveness to already established life-course trajectories, depend in part on whether they are expected or unexpected, as well as if they are considered “on-time” or “off-time.” Culturally based, age-graded norms determine whether a transition is deemed to be on-time or off-time. If a transition occurs during the culturally prescribed time frame, then it is considered to be on-time. In contrast, off-time transitions do not coincide with the expected timetable and often are associated with negative consequences. The timing of military service during young adulthood, as well as its timing in relation to the adoption of other salient roles, can have substantial consequences, as will be discussed in more detail below.

Fifth, the principle of linked lives focuses attention on the importance of social relationships and the interdependence of lives. As we move through various life stages, the composition of our “social convoy” (Antonucci and Akiyama 1995) shifts as we develop relationships with new members and connections to older members dwindle, evolve, or are severed. Members of our family of origin are often the most enduring members of our social convoy, moving with us through different phases of life. These inter- and intra-generational ties are among the conduits through which events in one person’s life impact other people. Additional conduits through which lives are linked include friendships and various types of community relationships (e.g., neighbors, school- or workplace-based peer relationships). For individuals whose lives are linked through various social relationships, events that occur in one person’s life can have ripple effects on the entire network. Those effects can be either positive or negative, depending in part on the degree to which members’ lives are synchronous or asynchronous. For example, the disruptiveness of deployment for military personnel and their families depends to some degree on life stage; deployments are likely to be less disruptive for a single, childless service member whose parents are healthy than for a partnered service member with young children and/or ailing parents. The armed forces have become increasingly attuned to the importance of families in the lives of military personnel since the shift to the All-Volunteer Force in 1973. Social network members (in particular family members) play a crucial role in recruitment into and retention in the armed forces. As discussed in various chapters in this volume, they are also involved in reintegrating veterans into the larger society and providing care for those with service-related injuries and disability. Although a focus on linked lives offers numerous sociologically rich possibilities to study military service in lives, as we shall see, there has been relatively little empirical life-course research that employs the linked lives principle to explore how the lives of family members, friends, and community members are shaped by the experiences of military personnel and veterans.

Building on these five principles, life-course researchers who study military service in lives have motivated and interrogated two corollary hypotheses that have wide-reaching implications: the military-as-turning-point and the life-course-disruption hypotheses. Both of these hypotheses emphasize the potential of military service to produce discontinuity in life-course trajectories, for better or worse. They also suggest mechanisms by which participation in the military during young adulthood influences cumulative inequality across the life course.

The military-as-turning-point hypothesis states that young age at entry into the military maximizes the chances for redirection of the life course and, assuming no service-connected injury or disability, minimizes disruption to established life-course trajectories. Elder (1986, 1987) argues that early entry into the military is like a social and psychological moratorium, which both delays the transition to adulthood and allows for the maximum utilization of Veterans Administration benefits. More recently, Kelty, Kleykamp, and Segal (2010) have argued that military service during the era of the All-Volunteer Force is one of many pathways to adulthood, rather than a delay or a detour in the process of transitioning to adulthood. Regardless of which theorization is adopted, for youth from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds, military service may be a route out of difficult life circumstances both because the transition to the military “knifes off” certain social ties and patterns of behavior and because it provides a “bridging environment” in which service members can obtain education, training, skills, and resources that put them on different and better life-course trajectories than they otherwise would have followed (Browning, Lopreato, and Poston 1973; Sampson and Laub 1996; see also Bennett and McDonald, Chapter 6 in this volume). While selection into the military on the basis of disadvantaged early-life circumstances would tend to correlate with worse life-course trajectories and outcomes among veterans, it has been theorized that early entrants are precisely the service members who benefit most from the range of service-connected benefits that are available to them and for whom military service is least disruptive. Of course, it is important to bear in mind that service-connected injury and disability can serve as a negative turning point in the life of any man or woman, regardless of age at entry into the armed forces.

The corollary life-course-disruption hypothesis suggests that relatively late entry into the military can disrupt established marital, parenting, and occupational trajectories, and that such disruption may have negative consequences for subsequent life-course trajectories and outcomes. Later entrants often come from more advantaged backgrounds, have completed their educations, and are embedded within established families and careers. Because of the timing of military service in their lives, they may have less opportunity to take advantage of GI Bill educational benefits and experience more life-course disruption. Notably among those who serve during war and experience combat, but even among those who are deployed but do not see combat, the physical and psychological effects of military service may intersect with disrupted occupational and family roles in ways that increase strain and the risk of marital disruption. The potentially disruptive consequences of later entry into active-duty service, exacerbated by service-related experiences such as deployment, combat exposure, and service-connected disability, may be particularly significant for men and women activated from the Reserves during times of war, because such occurrences are less expected by them and their family members. This is a particularly salient concern in the context of the contemporary wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Implicitly, studies about the influence of military service on lives, in general, and the tu...