- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Understanding Disability Studies and Performance Studies

About this book

This collection brings together scholarship and creative writing that brings together two of the most innovative fields to emerge from critical and cultural studies in the past few decades: Disability studies and performance studies. It draws on writings about such media as live performance art, photography, silent film, dance, personal narrative and theatre, using such diverse perspectives and methods as queer theory, gender, feminist, and masculinity studies, dance studies, as well as providing first publication of creative writings by award-winning poets and playwrights.

This book was based on a special issue of Text and Performance Quarterly.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Research Reports

Performing Amputation: The Photographs of Joel-Peter Witkin

The contemporary photography of Joel-Peter Witkin takes center stage in Performing Amputation. Many of his photographs feature amputee models in excessive and theatrical displays. The compositions recall, parody, and strategically corrupt traditions of bodily representation found in classical and neoclassical sculpture, ornamental motifs, the art historical still life, medical exhibits and photographs, and the early modern freak show. With the amputee body and amputating techniques, Witkin dismembers and sutures together multiple visual traditions. Witkin takes on the history of art and photography and effectively performs amputation on their visual conventions as he performs literal surgery on his images. His personal touch on the photographic plate and print perverts the assumed neutrality of the photographic gaze. The camera has been used as an instrument of medicine and of the gaze historically, a history in which Witkin’s images intervene. I argue that Witkin’s controversial and excessive photographs disrupt medical models for disability by presenting disabled and disfigured bodies as objects of art, design, and aesthetic magnificence, particularly because of their curious and spectacular, abnormal bodies. His camera both references and enacts images of objectification by displaying the body as an object. However, Witkin’s amputee and other disfigured subjects elect and even request to be photographed; they therefore collaborate with Witkin in their production as photographic spectacles. As stages on which these models perform, the photographs may serve as venues for progressive selfexhibition and unashamed parading of the so-called abnormal body.

The contemporary photographs of Joel-Peter Witkin are best described as corporeal tableau-vivants that showcase body difference, taboo, and abnormality. Critics have characterized Witkin’s controversial work as too perverse, too blasphemous, and too grotesque, and for many, his framing of disability is one of his most offensive orchestrations.1 Many such works feature amputee models and bodies in pieces in excessive and theatrical displays. These images of amputation are most extreme at the site of carnal extremities. In this paper, I explain how Witkin’s work with amputees performs amputation, in subject matter, formal techniques, and the theatricality of the models.

Witkin’s photographs of amputees, in which he removes limbs photographically or fetishizes the sites of amputation visually, offer a superlative example of how his photographic methods dismember histories of bodily display. Witkin dissects and sutures together multiple visual genres, such as art history, popular culture, pornography, theatre, medical exhibits and photography, and freak show displays. He targets the visual conventions with which these genres display the body and, specifically, how they produce the disabled or “abnormal” body as spectacle.

Performing amputation to his plates and prints, Witkin manipulates the flesh of his photographs in pseudo-surgical techniques. Witkin “doctors” the images to pervert the assumed objectivity of photography in general and clinical photography in particular. The camera has been used as an instrument of medicine and of the gaze since its nineteenth-century invention, a history in which Witkin’s images intervene. I argue that Witkin’s controversial and excessive photographs disrupt medical models for disability by staging amputees as objects of art, design, and aesthetic magnificence, particularly because of their curious and spectacular, abnormal bodies. Through Witkin’s lens, the medical gaze proves to be infected with voyeurism, desire, and repulsion. His blatant and significantly aestheticized objectification of amputee bodies elucidates the more deceptive objectification practices of clinical photography especially, in which amputees and so-called disfigured bodies were frequently represented and medically pathologized. Witkin poignantly pairs the conventions of medical imagery for diagnosing bodily difference with the traditions and motifs of classical art, which serve as a benchmark for ideal physical beauty in Western culture.

I will compare Witkin’s images of amputees with classical and neoclassical sculpture, ornamental motifs, the art historical still life, medical exhibits, the early modern freak show, the performative self-portraits of Frida Kahlo, and the work of contemporary disabled artists to elucidate the layers of body representation and exhibitionism in his work. Further, these comparisons frame the many means by which Witkin, his photographs, and his models perform amputation. As stages on which his amputee models perform their corporeal brilliance, the photographs may serve as venues for progressive self-exhibition and unashamed parading of bodily difference from the norm.

Witkin’s works foreground notions of photography as performative. From the 19th century to the present, photography has functioned to document performative media such as body art, installation, process and conceptual art, happenings, and oral poetry. Performance theorist Peggy Phelan (35–37) argues that all photography is performative, as subjects perform before the camera and perform the scenes they imagine the photographer is seeing or desires to see for the end image. Theorist Roland Barthes states that photography is essentially theatrical. Both Phelan and Barthes discuss the complicated dynamics of presence and absence of the body/self in photography. For Phelan, photography implicates the “real” through the presence of live bodies and, like performance, orchestrates an exchange of gazes between the viewer and the body depicted. However, Phelan points out that representations are always mediated and conceal more about their subject than they reveal, such that photography depicts only the surface of the body/self in its depiction of a staged, performative image. Barthes states that photography has an indexical relationship to its subject, containing the presence or trace of body in the image; however, because photographs bear only this deceptive trace, and never fulfill the real presence of the body (for example, of a loved one), Barthes theorizes that photographs embody absence and loss.

Performance theorist Rebecca Schneider describes this “live” aspect of performance and photography as engaging an explicit body – a literal, material body that complicates purely symbolic associations. The corporeal bodies of Witkin’s amputees similarly disrupt symbolic associations of fragmentation; their absence of limbs is “real” and yet gratuitously fictionalized by the photographs’ excessive displays. These works frame Barthes’s notion that photographs are always fragmented, amputated, already partial, and inevitably “unwhole.” For Barthes, photography’s withholding, “lack” of whole narratives, and inevitable absences create intrigue, mystery, and excitement and make all photographs infinitely sensual and abundant with meaning. Further, Barthes states that photographs are oversignified because they defy divisional categories, crossing contexts and genres. Performance theorist Henry Sayre likewise characterizes photography as oversignified. Sayre (59–60) uses the phrase “exceeds the frame” to describe contemporary photography’s, especially portraiture’s, characteristic of implying or projecting meaning that goes beyond the image—beyond language, facts, and narrative, and into viewer’s subjective, interpretive space. Witkin’s photographs, in their excessive and explicit displays, exceed their own frames. Sayre states (264): “The (film) still, the photograph, the fragment all reject the finality of ‘meaning’.” The amputee bodies Witkin features reject any closed or fixed interpretation of seeing and representing the body, particularly the amputee body, in visual culture.

Exceeding the Frame

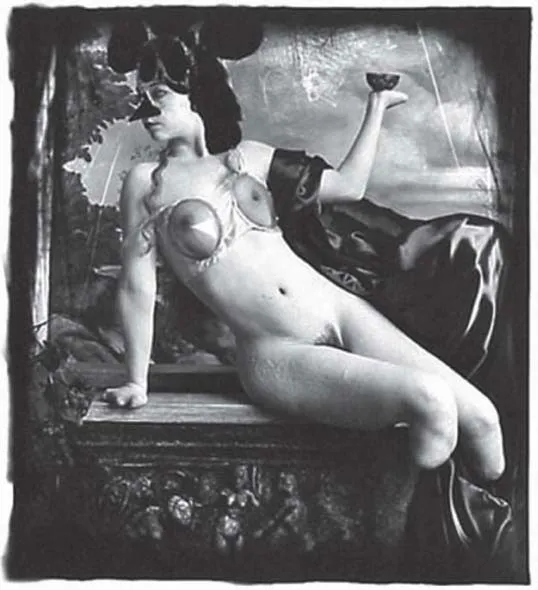

Joel-Peter Witkin’s photograph Humor and Fear (1999) (Figure 1) stages a female amputee model in a theatrical, pseudo-antique scene. The image crosses and combines multiple genres for body display: artistic, theatrical, medical, and freakish. She is posed nude on a pedestal or chest that resembles a classical sarcophagus with a figurative sculptural. She leans on one arm and hip, with her other arm raised to display a small bowl. Her posture is unnatural for a portrait subject, as her body becomes embedded in an allegorical program, like the ones carved in relief her pedestal. Surrounded by vegetal props that resemble a Greek entablature motif, the model is framed within a curved, darkened background that creates a proscenium arch—the symbol of Greek theatre. This background, printed in painterly, heavy inks, contrasts with the glaring whites of her marble-like skin and sets off her illuminated body as a decorative sculptural, architectural, or still life object. The marks Witkin has applied to the plate and the sepia washes over the print give the photograph an additional antique aesthetic. The model resembles a generic art historical nude, yet the photograph emphasizes the tangible materiality of her graphically naked, explicit body. The photographic medium highlights the texture of her flesh and pubic hair, which surpasses the illusion of marble and purely symbolic connotations; with scientific accuracy, the photograph emphasizes the tactility of the scene. The folds in her skin pair visually with the folds in an animated drapery that surrounds her body, climbs over one arm, and seems to have a life of its own, again contrasting with and highlighting the static, inanimate pose of the model.

Figure 1 Joel-Peter Witkin, Humor and Fear (1999). Reprinted with permission from Joel-Peter Witkin.

The qualities of “humor” and “fear” articulated by the title allude to the many paradoxes. The photographic frame and the numerous ambiguous details contribute to a multi-genre and infinitely suggestive tableau. The model dons a bra made of plastic cones that is translucent to reveal her erect nipples, emphasizing the materiality of her eroticized body. As a female body on display, partially nude to emphasize her nakedness, she is sexually objectified. However, the artificiality and excessive details, bordering on ridiculous, subtract this scene from a history of complicit and/or alluring female bodies on display for the viewer’s consumption. Her profile displays a pointy costume nose, another common feature that is broken in antique sculpture, yet here looks more like a Halloween mask, paired with Mickey Mouse ears. The humor of the scene is combined with its elements of fear, as the hybrid image juxtaposes seeming opposites. This title raises many questions, including whose “humor and fear” surround this body and its excessive photographic display—the model’s, the viewers’, and/or Witkin’s?

Despite the plethora of visual detail, the viewer’s eyes are drawn to the sites of the model’s impairments. The amputated stumps and “deformed” hands become objectified, like other parts of her costumed body, or fetishized, a theme which scholars have found to be characteristic of photographs of disabled bodies (Garland-Thomson, “Seeing the Disabled”). Rosemarie Garland-Thomson maintains that such fetishization of the body, derived from medical models, serves to eclipse the multidimensional nature of disabled subjects, constructing disability as social spectacle. In these frameworks, the image’s “offering” is an opportunity to gaze/stare at the amputee. The photograph’s narration in a book of Witkin’s works satisfies the viewer’s consequential desire to know what happened to make the body abnormal. The diagnostic text paired with the photograph states that the model lost her limbs as a young woman, due to toxic shock syndrome incurred from the use of a tampon (Parry 115). She has been amputated by medical procedures and as a consequence of using an implement marketed to women. Medicine has impaired her, as does this constructed image of her body. The scientific rendering of her body in photographic detail adds to her role as a medical specimen, subjected to a diagnostic gaze/stare. However, Witkin’s compositions refuse conformity to such predictable implications in their displays of the disabled body.

The image exceeds medical discourses in its blatant theatricality, and the artist’s personal touch on the photographic plate disrupts the illusion that photography produces and reproduces its subject scientifically. Witkin blows up the negatives of representation, so to speak, as he serves up the disabled body on a platter. In this and all of Witkin’s work, the fetishization of the body is fully sensationalized and made into a theatrical spectacle—fetishized bodies are spotlighted, placed on pedestals, and framed in excessive stage sets, which further exaggerates how all photography may be said to solicit a stare. Perhaps problematically, she is not posed to stare back at the viewer, which further objectifies her. In the image, her face is only half exposed as she turns away from the viewer’s gaze and stares beyond the frames of the image, perhaps in refusal of unlimited voyeuristic access to her body or to protect herself from a diagnostic stare. Or perhaps she turns away in shame for her bodily “tragedy” or from the perverse exploitation and objectification of her body in the photograph and in visual traditions throughout history. And yet the caption also introduces the model as a former gymnast and nude dancer—identifications and professions intensely centered on displaying the body. The model therefore may be quite comfortable in settings of bodily display and has indeed elected to pose for the artist. Witkin has said that the model responded to the finished photograph with pride, expressing that it made her feel beautiful.2 The excessive image frames how the amputee model’s body exceeds classifications and conventions of visual genres. The photograph intervenes in what the viewer may think they know about representation and about the disabled body. It strategically fools the eye. Her stumps appear photographically amputated in the image, as if Witkin has surgically removed them, causing the viewer to do a double take. The image becomes a performance of amputation, on the parts of the model and the artist.

The classical aesthetic Witkin employs and subverts has been similarly invoked by other contemporary artists. Like Witkin’s work with his models, the collaboration between artist Alison Lapper and sculptor Marc Quinn resulted in Quinn’s 13-foot, 12-ton marble statue that portrays Lapper’s full body in all her glory—seated nude and calmly displaying her armless torso, foreshortened legs, and rounded belly, seven months pregnant. Installed in the public tourist space of London’s Trafalgar Square and surrounded poignantly by statues of famous naval captains, Alison Lapper Pregnant (2005) (Figure 2) serves as a public performance of amputation. The work calls for re-examination of art and society’s ideals and notions of “whole” versus “broken” bodies. Quinn’s work is specifically a quotation of 18th- and 19th-century neoclassicism, which taught lessons on heroism and moral virtue, often by depicting the deeds of great and powerful men. Neoclassic...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- PROLOGUE

- RESEARCH REPORTS

- THE PERFORMANCE SPACE

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Understanding Disability Studies and Performance Studies by Bruce Henderson,Noam Ostrander in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.