![]()

Introduction

MANFRED B. STEGER & ANNE MCNEVIN

RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia

ABSTRACT This article introduces the central problematic behind this special edition: the intersection of language and space as reflected in the interplay of global ideologies and urban landscapes. We aim to illuminate and problematise the production of ideologies as both discursive and spatial phenomena by grounding our analyses in cities of the global North and South. We outline our reasons for this focus in relation to the prominence of space in contemporary social theory and in relation to more everyday local-global conditions. Specifically, we point to the declining availability of conventional ‘public spaces’ as sites of ideological dissent; the proliferation of ideologically embedded metaphors and neologisms that narrow the diverse potentials of spatial transformation; the constraints that disciplinary boundaries place on socio-spatial inquiry; and the normative drive to build heterogeneous futures other than those set out by elites as universally ‘global’. We outline the contributions to this special edition in relation to these key themes.

Este artículo introduce la problemática que constituye el tema principal de esta edición especial. La interacción de las ideologías de la globalización y el espacio urbano se reflejan en los cruces del lenguaje y el espacio. Con el fin de ilustrar y afianzar esta problemática, se analizara la creación de ideologías en ciudades globalizadas del norte y del sur como un fenómeno espacial y de discurso. A continuación enumeramos las razones de este enfoque con relacióin a la importancia del espacio en la teoría social contemporáinea y su relación cada vez mayor con las condiciones locales-globales del diario vivir. Senalamos específicamente el deterioro de la disponibilidad de ‘espacios públicoś como lugares para el disentimiento de ideologías; la proliferación de metáforas y neologismos enquistados que disminuyen el potencial diverso de la transformación de los espacios; las restricciones generadas por límites disciplinarios en la búsqueda socio-espacial; y, la tendencia normativa que busca construir futuros heterogéneos que difieran de los establecidos por las elites como globalmente ‘universales’. Los temas mencionados anteriormente, son claves para esta edición especial.

The central theme of this special issue is the intersection of discursive formations and social space as reflected in the interplay of political ideologies and urban landscapes. We take as our point of departure the premise that enquiry into the shifting grounds of contemporary ideologies requires close attention to the socio-spatial relations in and through which such ideational constellations assume concrete forms. At the most basic level, this starting point allows us to acknowledge the diversity of ideological production, application, and contestation in specific urban places and across different geographical scales. Such heterogeneity counters reductionist presentations of globalization as a homogenizing process of ‘McWorldization’ or ‘Americanization’. Moreover, it helps us to reconsider how spaces usually cast as ‘local’ connect in geographically challenging ways with what we imagine to be ‘global’.

However, the starting point for this issue also foregrounds the more fundamental relation between language and space that has inspired social theory’s ‘spatial turn’ in the 1980s and 1990s (Soja, 1989; Tonkiss, 2005). In other words, we wish to emphasize the co-implication of political ideologies and the constitution of space. Space, in short, is not a neutral background upon which or against which various ideological contests play themselves out. Political in itself, space contains our shared interpretation of places shaped through historically contingent social relations. This is not to suggest that particular places (regions, territories, cities, worksites, homes, meeting halls, and so on) are somehow unreal or less than concrete. It is rather to argue that the names we give to those places, the boundaries we allocate around them, and the role they play in shaping our sense of self are socially determined processes and therefore open to political contestation. When, for example, one particular way of framing space becomes naturalized, some political projects are enabled while others are constrained or even cast in such terms as ‘unworkable’ or ‘unthinkable’. Thus the constitution of space plays into the legitimacy of discursive formations and political ideologies thus shape (and, in turn, are shaped by) the various ‘scapes’ through which we come to know our social environments.

But why make this relation between language and space the focus of attention now? We do so for four fundamental reasons. The first is political and relates to our recognition of the importance of public space as a necessary condition for ideological diversity. Public or ‘civic’ spaces—places of inclusion open to a great variety of people and behaviours—are the arenas in which the terms of debates related to the social good are initiated and contested. As Rosalyn Deutsche (1996, p. 273) puts it, ‘What is recognized in public space is the legitimacy of debate about what is legitimate and what is illegitimate’. Yet, these civic spaces framing our ‘lifeworlds’ are always threatened by colonization from the state and private forces (Douglass, 2002). This ongoing struggle to maintain civic spaces is apparent not only in city squares where electronic advertising billboards crowd out community announcements and exclusive consumer establishments limit access to those citizens who can afford their goods and services. Moreover, the welcome rise of so-called ‘global commons’ and open-access domains of cyberspace has gone hand in hand with new digital technologies of surveillance and the rapid commodification of emerging civic spheres. Seeking to counteract these ominous transformations, vital democratic dynamics historically linked to thriving public spaces are rapidly running out of steam. Hence, the need to analyse critically how new and old spaces usually coded as ‘public’ or ‘civic’ become ideologically decontested and serve to normalize the truth claims of transnational power elites (Freeden, 1996; Steger, 2008).

The second reason for situating ‘the spatial turn’ at the forefront of contemporary discursive enquiry has to do with the ideological predispositions of the myriad of spatial narratives and metaphors that currently circulate in relation to globalization. Though the meanings and impacts of globalization remain broadly contested, recent literature on the subject suggests a growing consensus that our familiar time-space constellations have undergone significant change with serious implications for our modes of law and governance and our very human consciousness. At the dawn of a global age, these crucial changes owe much to the interplay of new socio-spatial relations and new ideological currents. Although space has always been political, the contemporary moment has ushered in spatial transformation in strikingly overt ways. We are daily confronted with new terminology that attempts to capture these new temporal-spatial dynamics and fashion them into regimes of knowledge about the way the world now ‘works’. Ceaseless flows of commodities, ideas, and people have launched us into what the hegemonic discourse likes to present as ‘inevitable’ and ‘irreversible’ forms of ‘global interdependence’. Other metaphors include ‘networks’, ‘nodes’, and ‘cells’ that are said to structure high finance and global terrorist activity. Cyberspace communities offer at once the promise of democratic invigoration and the threat of disembodied ‘second life’ fantasies. ‘Citizenship’ proliferates into transnational, post-national and cosmopolitan forms while at the same time jumping scale from local to global in the pursuit of consumerist dreams. Migrants shape their destinies through place-to-place connections that are more evocative of wormholes than of border-crossings and territorial expanse (Sheppard, 2002). As neologisms proliferate and old metaphors are reworked in the service of the new, the spaces of globalization emerge as new ‘common-sense’ arrangements embedded in political claims. In this crucial point of transition away from a weakening national consciousness toward local–global imaginaries, the contributors to this volume attempt to critically engage the central dimensions of globalization by drawing attention to the politics of space.

Thirdly, our attempt to link ideological narratives and urban space dovetails with our longstanding efforts to connect more closely language-based with space-based literatures in the critical social sciences. In a globalizing world where conventional European disciplinary frameworks are rapidly losing their rationale, it has become imperative to go beyond simply paying lip service to the new requirements of inter- and transdisciplinarity. This special issue represents one such initiative to unsettle established disciplinary territories. It has been specifically designed to bring together political geographers, sociologists, political and cultural theorists, and urban studies experts in a fruitful exchange of ideas. We allow for the cross-fertilization of literatures that, for far too long, have reproduced themselves in relative isolation. In this sense, then, this collection of essays seeks to contribute to the fledgling field of global studies, in which concrete research questions related to globalization take precedence over circumscribed concerns with disciplinary markers and traditions.

Finally, the spirit of this issue works against attempts to colonize the meaning of globality as a singular relation to space and the direction of globalization as a predetermined trajectory. We refer to discursive projects of this kind, in general, as globalism. But globalism comes in various forms. The market variety heralds a ‘liberated’ realm of global trade and consumer desires, while the religious-jihadist version seeks to subordinate world-space and world-time to ‘god-given’ forms of authority, unalterably etched in Holy Scripture (Steger, 2008). But we can also detect a ‘justice globalism’ of the transnational Left, although the various claims to ‘another world’ or ‘alter-globalization’ still await a more coherent ideological translation into a concrete political agenda. However sympathetic we may be to alternative readings of globalization that start from a global social justice framework, we must be on the guard against the drive to ‘get there’ via universalizing claims. Constituting indispensable mental maps that help us navigate our complex political universe, ideologies are not always ‘bad’—they also offer positive pathways to solidaristic bonds and collective moral decisions. Yet, it behoves us to maintain a critical gaze toward the ways in which ideological truth-claims may close down avenues of interpretation and narrow our engagement with the human diversity of being in space and time. As Doreen Massey notes, ‘Conceptualising space as open, multiple and relational, unfinished and always becoming, is a prerequisite for history to be open, and thus a prerequisite, too, for the possibility of politics.’ (Massey, 2005, p. 59)

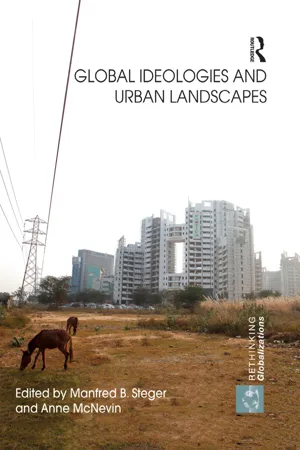

The contributors to this issue aim to illuminate and problematize the production of ideologies as both discursive and spatial phenomena. They do so by grounding their analysis in situated urban landscapes—in cities of the global North and South. While much of the literature on globalization has focused, often uncritically, on a nebulous realm of ‘the global’, studies based in urban experience have insisted on the place-specificities of ‘global’ transformations. The ‘global’ always manifests as the ‘local’. Most prominently, the best literature on global cities has shown how global capital relies on concrete local infrastructure in order to coordinate its vast transnational networks and that this place-boundedness has important implications for the spaces that shape our social, political, and economic relations (Brenner & Keil, 2006). Other scholars have looked to ‘ordinary’ and ‘postcolonial’ cities to show the many layers of globalization in realms beyond the economic that challenge prevailing assumptions about the necessary course of global urban development (Butcher & Velayutham, 2009; Robinson, 2006). In this issue, we look to the urban for the local production of globalization(s), in both material and symbolic forms. We also focus on urban acts of contestation. In recent years, diverse groups ranging from undocumented migrants and the marginalized urban poor to alter-globalization coalitions have mobilized to reclaim their rights to the city and to challenge the pathways to prosperity championed by proponents of market globalism—whether in relation to national labour markets, local urban planning, or techniques of global governance. Both ideological production and contestation in and through urban spaces offer insight into contending visions of the meaning of globalization assembled by the political forces of the Left and the Right in both the North and South.

The central theme (language and space) and the normative spirit of the project (to resist ideological convergence) required from the editors a willingness to direct the contributions towards key themes and questions while leaving the field open to diverse methodologies and sites of investigation. The approach to space that we advocate here—dynamic and heterogeneous—cannot be advanced if narrow restrictions are applied to the modes of enquiry of the subject-matter in question. We have tried to achieve a balance between openness and coherence by focusing on urban space, in all its rich diversity and endless permutations. This is not to say that non-urban spaces are any less transformed by processes of globalization or any less subject to ideological pressures. Nor is it to deny various urban sensibilities that now pervade many ‘rural’ places. Rather, it is to respond to the urban condition, which now characterizes the daily lives of a majority of the world’s population. Indeed, globalization can hardly be theorized apart from urbanization. More than at any time in modern history, the city has become the key site of interaction between local and global. While we emphasize a place-based approach, let us reiterate that simplistic dichotomies between local and global are not only intellectually misleading but serve specific political interests—those that profit from the notion of globalization as an authorless force from beyond, and those that privilege the local as an authentic space of resistance to colonization from above. We look to the urban from transdisciplinary perspectives in order to deepen our enquiry into space and to capture its transformative-emancipatory dimensions.

Inevitably, in a collection as diverse as this, a number of questions are raised about the nature of the cities under scrutiny, the frameworks we use to identify them, and the analytical and methodological tools that guide our overall enquiry. Provoking these questions has been part of the research process and has animated our discussions since our first meeting as a critical global studies group in December 2008 at RMIT University in Melbourne. For our common research project, the city remains a key problematic in itself. How can we conceptualize urban landscapes in ways that acknowledge ideological investment without degenerating into uncritical partisanship? If the category of the ‘urban’ is, indeed, derived from the churning of settlement types under different forms of capitalism, then the term itself remains deeply embedded within an inherited epistemology that must be exposed to critical reflection. This begs the question of how critical analyses of urban landscapes and global cities can maintain reflexivity with respect to varieties of capitalism and globalism. In many ways, the city is artificially (and dialectically) imposed on the narrow (and broad) socio-spatial relations in which city-dwellers live their everyday lives. More generally, therefore, our common pursuit uncovers inscriptions of meaning in space by problematizing existing analytical categories while experimenting with new ones.

In many ways, the common link between the contributions that follow is the lack of conceptual clarity around contemporary socio-spatial relations. If we are new cartographers then we come to our task without maps—or at least prepared to jettison or radically rework those maps to which we have become accustomed. If, in spatial terms, we are indeed on the precipice of the new—the collapse of conventional geographical scales—then we do not yet have the conceptual vocabulary to articulate what is happening. By historical standards, such a vocabulary is unlikely to emerge in terms that resonate with widespread collective experience until the transformation is well underway. In the meantime, we are compelled to recalibrate older terminologies and invent new ones, knowing that we are likely to raise more questions than we can answer at this time.

Finally, the question of time and temporal consciousness itself must necessarily frame our enquiry into global ideologies and urban space. In what ways are ‘new’ spatial concepts invested with universalizing temporal patterns? How are perceptions of contemporary transition located within a modernist hunger for ‘the new’? If First World/Third World and North/South binaries are justifiably subjected to critical scrutiny, then how do older temporal dichotomies between primitive and modern, backwardness and progress, barbarism and civilization, savagery and enlightenment, developed and underdeveloped, map onto unfolding geographies of globality?

The collection begins with Neil Brenner, Jamie Peck, and Nik Theodore’s article on neoliberalization. This contribution positions cities as much as other places, territories, and scales in view of a broader spatial logic of capitalism. In doing so, the authors seek to work at the meta-theoretical level, advancing debate on conceptual frameworks through which we engage both systemic and particular dimensions of contemporary ideology. The authors propose an analytical framework that takes the process of neoliberalization as its starting point. Neoliberalization, they argue, is a variegated, geographically uneven, and path dependent tendency for regulatory restructuring that has been globally operational since the 1970s. The methodological implications of starting from this basis include the necessity of ‘low-flying’ studies into socio-spatial specificities in particular sites and spaces, alongside and in relation to generalizing studies or ‘macrosocial frameworks’ that can track global circuits of ideology in which local sites are embedded. The authors go on to consider how enquiry into the prospects for counter-neoliberalization (the ‘after’ scenario) also requires this ‘big picture’ approach.

From here, the collection moves into specific city foci as empirical starting points for broader analytical and theoretical questions. Contestation over public space is the subject of James Goodman’s enquiry into ‘global summitry’ as a key strategy to position Sydney as a global city of the Asia-Pacific. Recalling a series of summits hosted in Sydney, from the World Economic Forum to APEC, he shows how the normalization of market globalist agendas takes place through the appropriation of local public space. In this place-bound moment of ideological production, elite codifiers of market globalism also generate potential for delegitimization. Goodman argues that protest action directed against the summits and specifically against prohibited public access to otherwise public space, provided publicity for alternative transnational agendas in local and global fora. Goodman theorizes this coming together of transnational coalitions in situated space as a critical public pedagogy—the articulation and circulation of possible futures other than those of market globalist dreams.

Margaret Kohn examines the phenomena of redeveloped industrial zones in North American cities to ask about specific cultural responses to globalization. She identifies Toronto’s distillery district as a space of nostalgia for an industrial past that eschews the intangible prosperity of post-Fordist finance in favour of reverence for the smal...