This is a test

- 218 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

New Kingdom Royal City

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

First published in 1997. The aim of this study is to re-appraise the evidence for planned communities in ancient Egypt by reviewing published and unpublished data along with my own fieldwork at the site of Deir el-Ballas.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access New Kingdom Royal City by Lacovara in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

CHAPTER 1

TOWN PLANNING IN ANCIENT EGYPT: HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

It is only within the last two decades that the emphasis in Egyptology has shifted from its preoccupation with the excavation of tombs and temples to habitations. As a result there are many gaps in our understanding of the development and variety of secular architecture in ancient Egypt.97 New information is constantly being amassed and much of what we currently know, based chiefly on pictorial representations and old excavations, will undoubtedly be subject to extensive revision.

Toponyms aside, the ancient Egyptian references to the subject of towns and cities are few, and there appears to have been little distinction made between the various classes of settlements (i.e., niwt, “city,” dmi, “town,” and wḥit, “village”).98 The term ḥwt appears to refer to centers of royal administration.99

The lack of textual information has led some scholars into suggesting that ancient Egypt was somehow peculiar, a “civilization without cities.”100 In refutation of earlier claims that Egyptian urbanism lagged behind the rest of the contemporary ancient world, Kemp has shown that Egyptian towns and cities showed approximately the same rank-size range as Mesopotamian settlements.101

One of the chief distinctions to be made in discussing the character of urbanism in the Nile Valley is that between naturally developing “organic” towns and “artificial,” specialized, or single function sites.102 Organic towns would have developed in some locality that was advantageous for human settlement, such as near cultivable land, watercourses, trade routes or any environment that would have attracted and supported colonization. Artificial settlements on the other hand, may be described as those deliberately created by the state for a specialized purpose such as a military outpost or a ceremonial center. Because such foundations are supported by the state, they do not need to take the local infrastructure as their principal consideration and are often unable to support communities after their original purpose has been fulfilled.

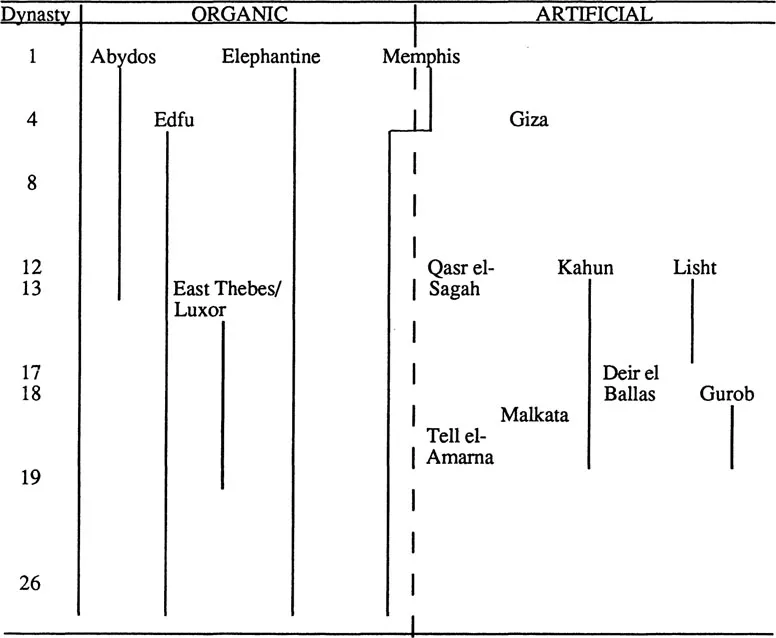

The dichotomy between these two classes of habitations dates back to the very beginnings of settled life in Egypt and continues throughout dynastic history.103 This pattern can be diagrammed as follows:

TABLE I Organic and Artificial Settlements in Egypt

Some of the identifications of the types of settlements shown above are based on very small archaeological exposures and are therefore tenuous.

These two classes of settlements, organic and artificial, need not be mutually exclusive. There may be overlap between these two sets of settlements, as, for example, where a new town is instituted and takes hold in an area that is efficacious for continued exploitation. Such an artificial community might also be set up on the margins of, or as an overlay onto, an existing community and eventually become part of the organic settlement. Such a dynamic can be found in Nilotic communities throughout the pharaonic period.

Predynastic settlements

The earliest dwellings found in the Nile Valley were circular structures, probably constructed of reeds. These hut circles were partially sunk below ground level and varied between three and seven feet in diameter. Such structures have been excavated at Matmar104 and Hemamieh105 in Middle Egypt and are dated to the Badarian Period. Similar houses with oval foundations ranging between ten and thirteen feet long have been found in Lower Egypt at the Neolithic sites of the Fayum, Merimde and El-Omari. It appears as though such hut circles are grouped in a rather open plan, as for example, in the settlement at Hemamieh.106

Granaries of basketwork covered with mud and buried in the ground were found in addition to houses within the settlement at Merimde.107 The Merimde dwellings were also semi-subterranean and were entered by means of steps and were also set fairly far apart. This type of expansive settlement pattern is clearly distinct from that found in the contemporary ancient Near East with larger populations housed in closely packed dwellings laid out contiguously in haphazard patterns.108

It has been suggested that the latter part of the predynastic period saw a change from simple, flimsy circular structures, which may have been seasonal habitations, to more substantial constructions. On the other hand, it may be that our sample may have been biased due to the destruction of more substantial, permanent, early villages in the valley.109

A clay model from a grave at El-Amra depicts such a permanent structure. It is rectangular in plan with slightly battered walls and peaked corners in imitation of wattle and daub construction. This model is a remarkably faithful rendering of a type of wattle and daub vernacular architecture still found in the villages of modern Egypt.110 Actual traces of such rectangular structures have been found in settlements at Maadi,111 Quft,112 and Hierakonpolis.113 Both at Quft and Hierakonpolis these dwellings are set apart from one another with a large amount of open space between them. Little is known about urban design at this early period. However, information from Hierakonpolis suggests that there may have been some rudimentary community organization evident in the town plan with industrial areas at the outskirts and temple/ceremonial structures in the center.114

Archaic Period Settlements

Settlement patterns seem to have undergone a major shift with the unification of Egypt in the Archaic Period. The settlement at Hierakonpolis moves into the floodplain and surrounds a vast temple-palace complex, and a new capital city is founded at Memphis. The founding of Memphis not only marks the beginning of the centralized, record-keeping state in Egypt, but may also set the pattern for the creation of royal cities as administrative centers. Contact with Mesopotamian civilization had a profound effect on all aspects of pharaonic culture at this formative stage. Elaborate construction in mud brick following the Mesopotamian niched-brick technique appears in depictions of temples and palaces on seals and tags and in a gateway found at Hierakonpolis. Unfortunately, excavations in this area of Hierakonpolis were not continued, and the reports are confusing. What was uncovered revealed a series of structures built within the gate on an orthogonal plan.115

Few houses of this early period have been found.116 It has been suggested that the Step Pyramid complex of Djoser at Saqqara represents a “model palace.” This structure, known as Temple T, is a long, narrow building with a rectangular columned entrance hall, a throne room, and a series of smaller rooms to the west.117

Old Kingdom Settlements

Associated with some of the pyramid complexes of the Fourth and Fifth Dynasties were a series of pyramid towns, which housed priests and personnel responsible for maintaining the cult of the royal pyramids.118 One of the better recorded of these settlements was the group of habitations excavated by George Andrew Reisner in the area of the Valley Temple of Mycerinus at Giza.119 Reisner perceived a number of building stages within the structure. The initial construction was that of the temple, while the last was a later intrusive settlement that extended eastward beyond the entrance of the temple. The houses were small rectangular structures of one to three rooms with associated round grain silos. The plan of the settlement evidences multiple periods of rebuilding and shows an organic pattern of growth developing out of what was initially an artificial, planned settlement.120

At Abydos, additional Old Kingdom structures have been discovered recently, including small thick-walled buildings with barrel vaulted roofs.121 Walled towns of the period have also been excavated at Ain Asîl in the Dakhleh Oasis122 and at Elephantine.123

The Old Kingdom town at Elephantine originally covered an area about 260 meters long and appears to have been zoned in several sectors, with a town wall at the southern edge, a temple at the northern perimeter, and areas of settlement and ceramic production.

First Intermediate Period and Middle Kingdom Settlements

We have even fewer settlement sites with domestic structures excavated from the Middle Kingdom than from the Old Kingdom. The archaeological record of this period, however, is augmented by a number of three dimensional representations of houses. These provide some information on the appearance of single dwelling units. Ceramic representations of private homes are found as offering basins placed above graves of the First Intermediate Period and early Middle Kingdom. These models, misnamed “soul houses,” vary in style from simple trays to detailed reproductions of domestic structures.124 Few actual settlements of the period have been excavated. At Abu Ghalib in the Delta, several rectangular houses were discovered, all oriented on a north-south axis.125 A large, planned settlement was associated with the pyramid complex of Sesostris II at Lahun.126 The town was constructed along an orthogonal plan and was subdivided into a number of zones with uniformly planned contiguous dwellings. The house units vary in size from less than 10 meters square to 40 × 60 meters for the most elaborate mansions. The latter have complex floor plans with a series of small rooms and magazines and larger columned rooms surrounding interior courts faced by peristylar porticoes. Entrance from the street was through a series of vestibules and long hallways.127

A much smaller planned community of houses was connected with the Middle Kingdom temple at Medamud.128 The houses here were built on a long rectangular plan, as at El-Lahun. Each dwelling was fronted by a court with a columned portico over the entrance. The interior plan included a central columned room with three smaller rooms grouped around it. The average size of these houses is roughly 20 meters long by 7.5 meters wide. Another orthogonal walled settlement has recently been excavated at Qasr el-Sagha. Here the individual houses appear to be less differentiated than in the other sites, but only a small portion of the settlement has so far been cleared.129

Other planned communities were found associated with a series of fortifications built along the Nubian frontier at the Second Cataract.130 This chain of massive mud brick fortresses served both as defensive garrisons and trading outposts and housed a complement of soldiers and their families. The forts vary widely in plan to take advantage of the local topography. The disposition of the settlements inside, however, appears more regularized with specific areas set aside for grain stores, habitation areas and administrative complexes.131

Little in the way of organic or unplanned settlement ha...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of Illustrations

- List of Tables

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Chapter 1. Town Planning in Ancient Egypt: Historical Overview

- Chapter 2. Domestic Architecture: Palaces

- Chapter 3. Domestic Architecture: Administrative and Support Buildings

- Chapter 4. Domestic Architecture: Workmen’s Villages

- Chapter 5. Domestic Architecture: Private Houses

- Chapter 6. The Royal City

- Chapter 7. Ancient Egyptian Urban Design

- Chapter 8. Deir El-Ballas and the Development of the New Kingdom Royal City

- Conclusion

- Sources of Illustrations

- Bibliography