This is a test

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Published in 1990, World Yearbook of Education 1990 is a valuable contribution to the field of Education.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access World Yearbook of Education 1990 by Tom Schuler, Tom Schuler in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Didattica & Didattica generale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. Quality control in British higher education

In the United Kingdom, all first degrees are, in principle at least, of comparable standard. Perusal of official and often ancient documents, which regulate universities, leaves little doubt that this notion of parity is deeply ingrained in British higher education. For instance, a passage from the 1843 University of Durham Calendar asserts: The standing of the degree of B.A., as for all other degrees, is the same as that which is required at Oxford’. The charter of the Victoria University (Manchester), 1888, requires that examiners be appointed from other universities for all degrees, for the evident purpose of ensuring that standards (in words taken from the regulations of London University, but typical of others) ‘are consistent with that of the national university system’.

The reference to a national system is revealing because constitutionally no such system exists: each university is a discrete and autonomous entity, awarding its own degrees under a charter from the Crown. The polytechnics and colleges, on the other hand, can be said fairly to be part of a single system, at least for the award of degrees. These institutions do not possess their own charters, rather their degrees are given under a charter held by The Council for National Academic Awards (CNAA). Thus, whereas the universities are free to adopt whatever standards they wish, the rest of the higher education ‘system’ is not. In fact the universities have always maintained an accord on standards and the CNAA chose to join them: until 1988 the Council’s regulations required that its degrees be ‘comparable to the standard of an award conferred by universities in the United Kingdom’. Thereafter, the reference was dropped, on the grounds that the Council’s standards were well established.

What is implied by this ideal of a universal standard? Clearly, more than one form of parity. There must be consistency within a degree programme, especially parity between course options. Standards must remain reasonably constant from year to year. Courses in similar subjects must be taught by all institutions to a similar level and the examinations marked to similar standards. It is also clear from the regulations quoted above, that standards are to be consistent between subjects. This view was recently reaffirmed by the Lindop Committee.1 Implicit in this view is the notion of a quality of academic work which is independent of subject matter yet is manifest in all disciplines. (Or, at the least, sets of equivalent qualities which allow examiners in different subjects to discriminate between degree classes in ways which agree.) A further implication is that all examiners have a grasp of this common notion and can apply it consistently in drawing distinctions between several levels of student performance.

Implicit in the ideal of parity between all degrees, then, are a number of assumptions first, about the kinds of comparisons which might be made to establish the marking standards, and secondly, about the ability of examiners to make certain kinds of discrimination. They are assumptions which invite scrutiny. A recent investigation2 undertaken by the author throws light on some pertinent questions and summaries of selected findings are presented below.

Four kinds of parity were identified above. First, a degree programme must be internally consistent, the same standards must be applied when marking all assessed work which counts towards a degree.3 Achieving such consistency within a programme raises some problems. One such problem concerns the application of consistent standards to the marking of work done under different conditions - say, that done during a three-hour invigilated examination and that produced as a project completed under supervision over a period of months. The question is whether or not the marking should take into account the conditions under which the work was done. If the answer is ‘no’, then we might expect to get very different ranges of marks for work done under different conditions. As a consequence the distribution of degree results would be partly a function of the assessment methods chosen. If the answer is ‘yes’, we invoke the need for some kind of conversion table, understood and consistently applied by all markers.

Another problem concerns the marking standards to apply when some of the examined work is done before the final year. Should early work be marked to the same standard as the final examinations or should it be marked as, say, second-year work? Again, the second option implies some consistent and shared notion of standards not only for final-year work but for every year of a course. The task is further complicated if an elective course may be taken by students in different years.

To understand the potential significance of these problems we must first enquire into the combinations of work which typically contribute to assessment for a degree. The first problem concerned work done under different conditions. How many degree courses involve projects and other kinds of course work? Course leaders were asked the question and the results are presented in Table 1:

Is work other than that done under examination conditions, taken into account when determining students’ final grade or marks?

| Univ* | P&C** | |

| Yes, all students | 77% | 94% |

| Yes, for some students or course options | 18% | 4% |

| No | 4% | 1% |

*Universities. **polytechnics and Colleges

Table 1

Table 2

there are very few degrees indeed which are awarded solely on the basis of ‘traditional’ invigilated examinations.

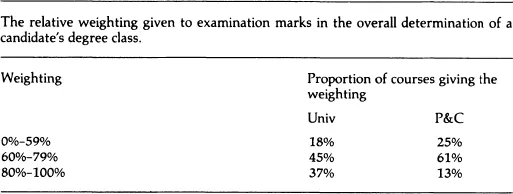

How much weight is given to the marks awarded for examination performance compared with assessed course work of various kinds? Table 2 gives a summary.

From these data we can conclude that the resolution of the problem of how to reconcile the marking standards applied to different kind of work is potentially a major determinant of overall degree standards. It follows that if the issue is resolved inconsistently or differently from one course to another the ideal of parity becomes difficult to achieve.

What of standards? We might postulate that if the same standards are applied to project work as to examination scripts, the marks will be affected in two ways: the project marks will be higher and the variation between them will be less because students will continue to work on their project until they are likely to earn the required mark.

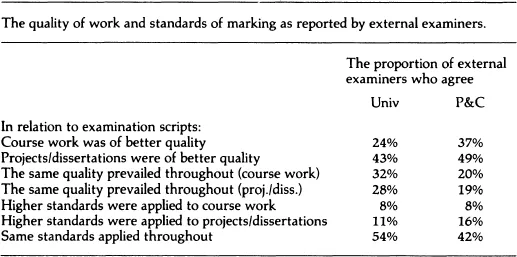

External examiners were asked both about the quality of candidates’ work and about the standards by which it was marked. The results as they relate to course work and to projects or dissertations are summarized in Table 3. They suggest considerable variation between examiners’ views on quality and inconsistent approaches to the adjustment of standards to take account of context.4

Assuming that the external examiners’ views are correct we may conclude that the quality of course work and projects is higher than examination answers in a substantial number of cases but that the cases in which compensatory marking standards are applied is considerably less. More examiners report the same marking standards being applied to all kinds of work than the number who report the quality of work being the same, which implies that there are courses in which the distribution of marks is partly determined by the method of assessment.

The survey revealed no direct evidence that the range of marks on course work or projects was restricted although that was the view of some examiners among those who were interviewed. Should it be so, the possibility arises that on some courses items which carry the majority of examination marks are also the items which discriminate between the candidates the least, implying that items with low weightings are the critical determinants of overall degree class.

Table 3

Such an outcome, should it occur, is presumably, the exact opposite of the intention behind the weighting scheme.

Overall it seems probable that there are a substantial number of courses in which marking standards are held constant regardless of the kind of work being marked, with the result that each kind of work yields a different distribution of marks with a consequent effect on overall degree standards. There are other courses where an attempt is made to take into account the conditions under which work has been done. The difficulty in those instances is putting some consistent numerical value on a qualitative difference which is likely to affect candidates in different ways (for example, one student might excel in formal examinations where another’s temperament is better suited to project work). The survey yielded no quantitative data on the point but some written answers to open-ended questions referred to the matter. One respondent, for example, wrote:

An insolvable problem. There are so many uncertainties involved in the appraisal of course work that this is one of the main causes of imprecision in the examination process (eg the candidate who fails in the paper but passes overall on the basis of course work which may be suspect).

The second dilemma mentioned above referred to marking ‘early’ work: should it be marked at the same standard as final-year work if it counts towards the degree? The problem affects a large number of courses as returns to the survey suggest that on 78 per cent of courses candidates’ degree results depend partly on work or examinations undertaken prior to the final year. The survey produced no statistical data on the weighting given to ‘early’ work in the computation of degree results. The general rule is that final-year work has the greatest weighting, yet work from previous years commonly counts for one-third of the total marks.

Course leaders and external examiners give compatible replies when asked about the relative standards applied to marking early work. Table 4 summarizes the answers given by course leaders and Table 5 the answers given to a similar enquiry of external examiners.

Is any of the work from previous years marked to a different standard than that from the final year?

| Univ | P&C | |

| Yes | 15% | 30% |

| No | 82% | 63% |

Table 4

A similar pattern emerges to that from the questions about course work: on the majority of courses the same standards are maintained but there is a substantial minority of courses where some form of compensation is attempted. Examiners were asked if they were aware of any problems or ambiguities over the standards by which ‘early’ work was assessed. Eleven per cent reported that they were.

It seems clear that practice varies, and, prima facie, we might infer that the standards of degrees vary as a consequence. Of course, it is theoretically possible for the variations in marking standards to be compensated by weighting marks or by examiners taking into account the difficulty of the material.

The second form of parity identified above concerned standards from year to year. Course leaders were asked whether the examined work was judged against standards of work of candidates completing the same course in previous years. Twelve per cent of the respondents reported that such comparisons were not made, but only 7 per cent said that the comparisons were made directly between the work from different years. The remaining 80 per cent said that comparisons were made ‘from memory and experience’. Only 4 per cent of course leaders reported that external examiners would have a selection of scripts from previous years, but 55 per cent said that they would have the distribution of marks from previous years. However, only 18 per cent of the sample of external examiners said that they had received a summary of the previous year’s marks; most of whom (16 per cent) found it useful. Among the 82 per cent who did not receive a summary were 23 per cent who believed they would have found it useful.

Were the standards applied when marking work produced before the final year the same as those applied when marking work during the final year?

| Univ | P&C | |

| Yes | 67% | 58% |

| No | 12% | 25% |

Table 5

We may conclude that the ideal of consistent standards from year to year is widely accepted but that a good deal of reliance is placed on examiners’ ability to carry the standard in their memory from one year to the next. ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of contributors

- Introduction

- 1. Quality control in British higher education

- 2. Raising educational standards - improving the quality of higher education

- 3. Assessment, technology and the quality revolution

- 4. Educational change and assessment in the age of information technology

- 5. Adjusting the balance of power: initial self-assessment in study skills for higher education a case study

- 6. Some implications of student choice of course content for the processes of learning, assessment and qualification

- 7. Assessment issues in relation to experience-based learning on placements within courses

- 8. Performance measurement in higher and continuing education

- 9. Evaluation: a problem-solving activity?

- 10. Evaluating large-scale, computer-related educational activity: an example from The Netherlands

- 11. The evaluation of the educational section of the Dutch Informatics Stimulation Programme (INSP)

- 12. The Italian school system

- 13. Class-group constitution procedure based on student assessment

- 14. Diagnostic testing in formative assessment: the students as test developers

- 15. Assessing and understanding common-sense knowledge

- 16. The area of social history: what to assess and how to assess it

- 17. Aptitude tests as the predictor of success in the Israeli matriculation

- 18. An unbiased, standardized method for quality in student assessment at the post-secondary level

- 19. Optical mark reading technology in Chinese educational development

- 20. Profiling: the role of technology

- 21. Teacher evaluation as the technology of increased centralism in education

- 22. Educational developments in the mountain kingdom of Bhutan

- Bibliography

- Contributor details

- Index