![]()

Global field and global imagining: Bourdieu and worldwide higher education

Simon Marginson

Centre for the Study of Higher Education, University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

This paper maps the global dimension of higher education and associated research, including the differentiation of national systems and institutions, while reflecting critically on theoretical tools for working this terrain. Arguably the most sustained theorisation of higher education is by Bourdieu: the paper explores the relevance and limits of Bourdieu’s notions of field of power, agency, positioned and position-taking; drawing on Gramsci’s notion of hegemony in explaining the dominant role played by universities from the United States. Noting there is greater ontological openness in global than national educational settings, and that Bourdieu’s reading of structure/agency becomes trapped on the structure side, the paper discusses Sen on self-determining identity and Appadurai on global imagining, flows and ‘scapes’. The dynamics of Bourdieu’s competitive field of higher education continue to play out globally, but located within a larger and more disjunctive relational setting, and a setting that is less closed, than he suggests.

Introduction

Worldwide higher education is a relational environment that is simultaneously global, national and local (Marginson and Rhoades 2002; Valimaa 2004). It includes international agencies, governments and national systems, institutions, disciplines, professions, e-learning companies and others. Although most activity in higher education is nation-bound, a distinctive global dimension is growing in importance, connecting with each national system of higher education while also being external to them all.

Although the global dimension has many roots, it above all derives from the worldwide rollout of instantaneous messaging, complex data transfer and cheapening air travel. The cross-border dealings of research-intensive universities and the relations between governments on higher education are something more than a mass of bilateral connections. There are networked global systems with commonalities, points of concentration (nodes), rhythms, speeds and modes of movement. In research there is a single mainstream system of English-language publication of research knowledge, which tends to marginalise other work rather than absorb it. There are converging approaches to recognition and quality assurance, such as the Washington Accords in Engineering. The Bologna agreement facilitates partial integration and convergence in degree structures and the diploma supplement in Europe.

The practices that distinguish higher education from other social formations are the credentialing of knowledge-intensive labour, and basic research. We can understand the global dimension of higher education as a bounded domain that includes institutions with cross-border activities in these areas. Although this domain is frayed at the edges by diploma mills, corporate ‘universities’ and cross-border e-learning – and despite its connections with other social formations – its boundedness and disinctiveness are irreducible. A dual of inclusion/exclusion shapes the outer and inner relationships of the domain. This suggests Pierre Bourdieu, who terms such domains as ‘fields of power’. Such as field is ‘a space, that is, an ensemble of positions in a relationship of mutual exclusion’ (Bourdieu 1996, 232).

Any theorisation of this global higher education domain must account for two elements. One is cross-border flows: flows of people (students, administrators, academic faculty); flows of media and messages, information and knowledge; flows of norms, ideas and policies; flows of technologies, finance capital and economic resources. Global flows in higher education are exceptionally dynamic and uneven. In the decade from 1995 to 2004 the number of students enrolled outside their country of citizenship rose from 1.3 million to 2.7 million (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development 2006, 287). Cross-border research collaborations and institutional partnerships are expanding rapidly (for example, Vincent-Lancrin 2006); when networks grow, the cost rises in linear fashion but the benefits rise exponentially via the increasing number of connections, while ‘the penalty for being outside the network increases’ (Castells 2000, 71). Global flows constitute relatively visible lines of effect. The other less explicit element is the worldwide patterns of differences that channel and limit global flows: lateral diversity in languages, pedagogies and scholarship, and in organisational systems and cultures; vertical diversity including competitive differentiation, hierarchy, inclusion, exclusion and unequal capacity. Global higher education is not a level playing field.

This paper is concerned with a synthetic mapping of the global dimension of higher education and research in terms of relations of power, including self-determining human agency, in order to contribute to understandings of global transformations (Held et al. 1999) in and through higher education. The paper draws on theorisations by Bourdieu and Antonio Gramsci and on discussions of global ontology and agency by Arjun Appadurai and Amartya Sen. Although this is not an empirically-driven study, data from OECD (2006), World Bank (2007) and other sources are used.1 The paper considers higher education without interrogating its relations with other fields of power in the economy, military, government, polity, communications and elsewhere. Those are matters for further synthesis.

Bourdieu and the global field of higher education

Arguably Bourdieu’s work on higher education (including Bourdieu 1984, 1988, 1993, 1996) is the most sustained of any major social theorist. Rajani Naidoo (2004) uses Bourdieu to analyse the differentiation of higher education institutions in South Africa. She notes, however, that Bourdieu’s argument developed in the context of a relatively stable compact between higher education, society and nation-state (Naidoo 2004, 468–469); and he has little to say about the structuring and content of knowledge. Further, much of his empirical research was in the 1960s prior to contemporary globalisation. Can Bourdieu assist our imaginings of global higher education given he is nation-bound and knowledge formation is both primary to universities and quintessentially global? Yes, with some qualifications. The qualifications will be discussed below but Bourdieu’s notion of field of power, with agents ‘positioned’ and ‘position-taking’ within the field, continue to be a useful starting point.

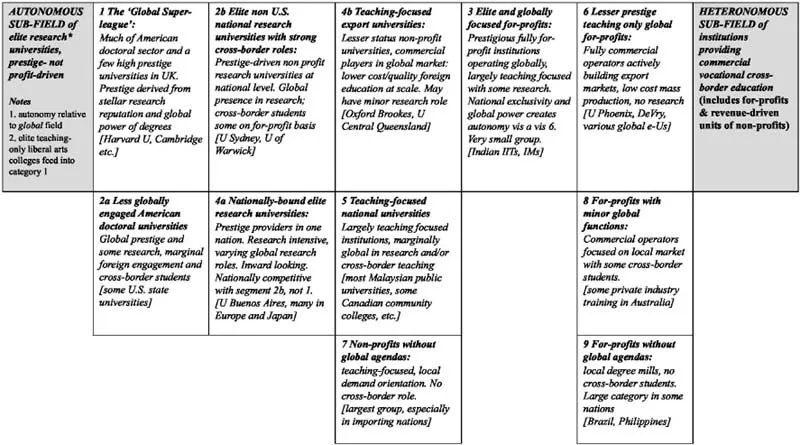

Polar structure of the global field

For Bourdieu a field of power is a social universe with its own laws of functioning. It enjoys a variable degree of autonomy, defined by its ability to reject external determinants and obey only its own specific logic. In The Field of Cultural Production (Bourdieu 1993, 38–39) he finds that the field is structured by an opposition between the elite subfield of restricted production, and the subfield of large-scale mass production tending towards commercial production. Each subfield has its distinctive principle of hierarchisation. In the elite subfield, where outputs are scarce, the principle of hierarchisation is cultural status, autonomous and specific to the field. In mass or ‘popular’ institutions the principle of hierarchisation involves economic capital and market demand and is heteronymous, although mass institutions renew themselves from time to time by adapting ideas from the elite sector. Between the subfields are found a range of intermediate institutions that combine the opposing principles of legitimacy in varying degrees and states of ambiguity.

Bourdieu’s polarity helps to explain relations of power within national systems, where heteronomy is shaped by governments, market forces and both together. The contrast in South Africa between the more autonomous white English-language universities focused on products for the intellectual field and more heteronomous black universities and white Afrikaans-medium universities (Naidoo 2004, 461) is replicated in the differentiation of the Australian system with its polarity between more autonomous and selective ‘sandstone’ universities that see themselves as global research players, and more heteronomous vocational and regional institutions (Marginson and Considine 2000, 175–232). Other examples can be cited. Far from making a universal journey from elite to mass higher education (Trow 1974), national systems contain both kinds of institution simultaneously and/or sustain the Bourdieuian polarity inside single institutions. However, the point here is that this Bourdieuian polarity is apparent also in the global field.

In the global subfield of restricted production are the American doctoral universities led by Harvard, Stanford, MIT, Yale, Princeton, Berkeley and others, plus Cambridge, Oxford and a handful of the Russell group. Ultimately they derive global predominance from their position within their own national/imperial systems. The Economist (2005) christened them the ‘Global Super-league’. These institutions constitute advanced careers almost anywhere in the world. Places are prized by both students and academic faculty. Selectivity is enhanced by modest student intakes, and they concentrate knowledge power to themselves by housing most leading researchers. They head the world in research outputs as measured by the Shanghai Jiao Tong University (SJTU) (SJTU Institute of Higher Education 2007).2 The top 20 SJTU universities are 17 from the USA, and Cambridge, Oxford and Tokyo. Largely autonomous, their agency freedom is enhanced by the globalisation of knowledge and their pre-eminence displayed in the web, global university rankings and popular culture. The global power of these institutions rests on the subordination of other institutions and nations.

In the opposite subfield are institutions solely focused on revenues and market share. This includes not only for-profit vocational universities such as the University of Phoenix, now active in a dozen countries, but in their global teaching function non-profit universities in the United Kingdom and Australia that provide international education on a commercial basis.

There is a range of institutions in intermediate positions (Figure 1). Some universities have elite roles in their national field and compete in the global research stakes while building high volumes of full fee-paying international students (category 2b); some other national leaders lack a strong global presence (category 4a). Beneath both groups are ostensibly teaching-research universities for whom the research mission is subordinated to cross-border revenues (category 4b). For-profit institutions vary in the extent to which they sustain a global role (categories 3, 6, and 8). Other institutions are solely nation-bound but nevertheless affected by the global field, for they are subordinated by it (categories 7 and 9).

Bourdieu’s notion of a differentiating field of power that includes/excludes is closer to the dynamics of higher education than is the neo-liberal imaginary of a universal market. However, in some respects the polarity differs from Bourdieu’s description. Anglo-American universities have not adopted the French division between high intellectual schools and those preparing the business elite. The Super-league universities combine the two functions, increasing their weight and integrating them closely at the centre of economic and political power. Further, elite universities, particularly the US Ivy League, are not just status dominant but economically dominant vis-à-vis mass producers. The Super-league command extraordinary resources: for example, the Harvard endowment, the commercial presence of American research universities in bio-science. Nevertheless Bourdieu is right to state that more autonomous universities are less commercial in temper. Super-league universities do not expand willy-nilly to maximise market share like a capitalist business. Their authority derives not from their equity price but from their selectivity and knowledge. They maximise not sales but research impact. Their lodestone is not revenues but social power. Where they run commercial suboperations, the resulting tensions are absorbed within the institution, playing out inside research programmes that are alternately fundamental and commercial (the two are mixed together almost irretrievably in bioscience) and in the cultural differences between arts/disciplinary science and business studies.

Figure 1. Polar field of global higher education, after Bourdieu.

Note: Horizontal axis maps autonomy/heteronomy. Vertical axis maps degree of global engagement. Numbers signify order of status in the global field.

Position and position-taking

Within a field of power, agents compete for resources, status or other objects of interest. Bourdieu describes an inter-dependency between the prior positions of agents and the position-taking strategies they select.

Every position-taking is defined in relation to the space of possibles which is objectively realized as a problematic in the form of the actual or potential position-takings corresponding to the different positions; and it receives its distinctive value from its negative relationship with the coexistent position-takings to which it is objectively related. (Bourdieu 1993, 30; emphasis in original)

Position-taking is the ‘space of creative works’ (p. 39). This is not an open-ended free-wheeling creativity. Only some position-takings are possible, identified by agents as they respond to changes in the settings and the moves of others in the competition game. Agents have a number of possible ‘trajectories’, the succession of positions occupied by the same agent over time, and employ semi-instinctual ‘strategies’ to achieve them. Agents respond in terms of their ‘habitus’, their acquired mix of beliefs and capabilities, and in particular their ‘disposition’ that mediates the relationship between position and position-takings (Bourdieu 1993, 61–73).

This schema is consistent with much of the evidence on the decisions of university executives as they strive for relative advantage (for example, Marginson and Considine 2000, 68–95). Bourdieu’s concepts of positioned/position taking can be applied in situated case studies (Deem 2001) of the strategies of universities each with its distinctive habitus. Specific national trajectories can be identified in, say, China, Singapore and Australia (Marginson 2007). Nevertheless, there are questions about how much room is left for self-determining agency. Bourdieu claims a reciprocity between structure and agency. ‘Although position helps to shape dispositions, the latter, in so far as they are the product of independent conditions, have an existence and an efficacy of their own and can help shape positions’ (Bourdieu 1993, 61). ‘The scope allowed for dispositions’ is variable, being shaped by the autonomy of the field in relation to other fields, by the position of the agent in the field, and by the extent to which the position is a novel and emerging one, or path-dependency has been established (1993, 72). But the ‘in so far as’ creates ambiguity. Bourdieu also fails to distinguish hierarchy from overwhelming power within a field such as higher education. This problem will considered first, before returning to agency.

Gramsci and global university hegemony

Here Bourdieu is usefully supplemented by Antonio Gramsci with his notion of egemonia (hegemony). Gramsci couples and contrasts two regimes of power. The first is domination or coercion by the open state machine, the ‘State-as-force’ (Gramsci 1971, 56). The second is hegemony, ‘the “spontaneous” consent given by the great masses of the population to the general direction imposed on social life by the dominant fundamental group’ (1971, 12). Hegemony is secured primarily in civil society, including education (Gramsci 1971, 12). It is a social construction in the realms of intellectual reason, institutions and popular culture in which a certain way of life and thought is diffused. There are parallels with Foucault’s (1991) distinction between political sovereignty and government as the conduct of conduct permeating all aspects of life. Like Foucault, Gramsci emphasises that the two regimes constitute mutually dependent strategies. Rule by consent is ultimately underpinned by rule by force (Gramsci 1971, 10).

Civil institutions like universities are analytically distinct from the state (political society) but intertwined with it. Tradition is an active, shaping force in making hegemony. Certain meanings and practices are selected into the common tradition. Elite universities secure their role as manufacturers of tradition, distinct from other universities, with symbols of venerability such as roman numerals and baroque stone. Does Gramsci see hegemony with its grounding in city states and nations as potentially global? Yes.

Every relationship of ‘hegemony’ is necessarily an educational relationship and occurs not only within a nation, between the various forces of which a nation is ...