![]()

Representing practice: practice models, patterns, bundles…

Isobel Falconera, Janet Finlayb and Sally Fincherc

aCaledonian Academy, Glasgow Caledonian University, Glasgow, UK; bTechnology Enhanced Learning (TEL), Leeds Metropolitan University, Leeds, UK; cSchool of Computing, University of Kent, Canterbury, Kent, UK

This article critiques learning design as a representation for sharing and developing practice, based on synthesis of three projects. Starting with the findings of the Mod4L Models of Practice project, it argues that the technical origins of learning design, and the consequent focus on structure and sequence, limit its usefulness for sharing practice between teachers. It compares practice models with two alternative, more flexible, representations, patterns and bundles, based on the outcomes of the Pattern Language Network (Planet) project and of the Centre for Excellence in Teaching and Learning: Active Learning in Computing (CETL ALiC). It concludes that while practice models may be useful in mediating between teachers and technical developers, they cannot encompass the range of practice teachers require to represent. A pattern language is more comprehensive and has the advantage of being generative, but is difficult for teachers to acquire, and bundles may provide a more adoptable representation.

Introduction

Learning design has two different roots within the field of technology-enhanced learning. The first of these is in the attempt to build computer systems that would orchestrate the delivery of learning resources and activities for computer-assisted learning. It is exemplified by developments such as the IMS Learning Design1 specification (IMS 2003), the attempt to build a learning activity reference model (Falconer et al. 2006; Falconer 2007), a Shareable Content Object Reference Model (ADL, 2004) and the Learning Activity Management System (LAMS) engine (Dalziel, 2003). The second is in the need to find effective ways of sharing good and innovative practice in technology-enhanced learning. It responds to recognition that, despite excitement and belief in their potential by developers, teachers have been slow to adopt such methods; in this formulation learning design is an aid to efficiency and professional development for teachers, and examples include Australian Universities Teaching Committee (AUTC) learning designs (Bennett, Agostinho, and Lockyer 2005), DialogPlus (Conole and Fill 2005), LAMS sequences (Dalziel 2003), and pedagogical patterns (Goodyear and Yang 2008).

These roots came together in the concept of ‘design for learning’ as defined by the UK Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC) in its ‘Design for Learning’ programme that ran through 2006–2007 (JISC 2006a): a desire to describe the orchestration of learning activities in a way that might be managed and delivered by computer; and a desire to find representations that would enable the sharing of innovative technology-enhanced teaching practice as an aid to professional development for teachers. Thus the programme defined a learning design as the outcome of the process of, ‘designing, planning and orchestrating learning activities as part of a learning session or programme’ (JISC 2006b, 1), while explaining that the purpose of the programme was ‘to develop further the community’s understanding of the principles that inform the design of effective learning activities which involve the use of technology’ (JISC 2006a, 1). In this article we adopt the JISC definition of learning design (JISC 2006b, 1).

A learning design may exist purely in the head of the teacher implementing it, especially in higher education. However, as Vogel and Oliver point out, ‘in order to be comprehended by others, designs must also be represented or articulated’ (2006, 4). However effective a design may be, it can only be shared with others through a representation. Efficient sharing and reuse can take place only if the representations are effective; they must convey the information that teachers need in a form that teachers can understand. The issue of representation, then, is central to the whole drive to share and reuse designs.

This article presents a critique of learning design, based on synthesis of the outcomes of three projects from the viewpoint of the second aim, that is, to find effective ways of sharing good and innovative practice in technology-enhanced learning. The projects were:

• Mod4L: Models of Practice project funded by the JISC under its Design for Learning programme.

• Pattern Language Network (Planet) project funded by the JISC under its Users and Innovation programme (http://www.jisc.ac.uk/whatwedo/programmes/usersandinnovation.aspx).

• CETL ALiC (Centre for Excellence in Teaching and Learning: Active Learning in Computing) funded by the Higher Education Funding Council of England (http://www.dur.ac.uk/alic).

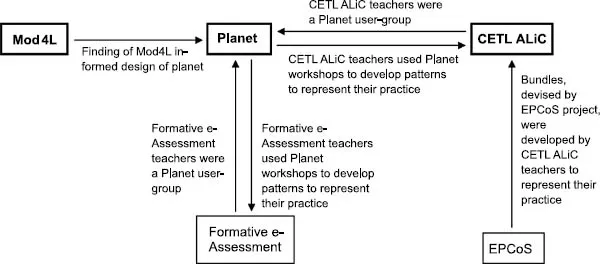

The relationship between these projects, and two others mentioned in the article, is summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Relationship between the projects discussed (top row, bold) and mentioned (lower row) in this paper.

Based on the experience of the Mod4L project with practice models, we argue that there is a need to capture, represent, and share intrinsic aspects of teaching, if teachers are to adopt new technology-based teaching methods with confidence. By intrinsic aspects of teaching we mean essential practices that are not immediately apparent from outward inspection of the structure of a lesson or activity. Such aspects are not well captured or represented by conventional learning design because its technical origin has led to a focus on sequencing and structure. The need to represent intrinsic practices has become even more acute in the past couple of decades with the rise of social constructivist and situative approaches to teaching (see, e.g., Mayes and de Freitas 2004; Conole and Fill 2005) and of Web 2.0 technologies, which are widely seen as promoting a less directive role for the teacher (Dron 2007; Selwyn 2008). Advance sequencing and orchestration may even be mitigated against (Beetham 2008; Pata 2009), and the role of the teacher becomes to help learners to manage the contingency of living in a learning environment – a role in which familiarity with intrinsic aspects of teaching is crucial.

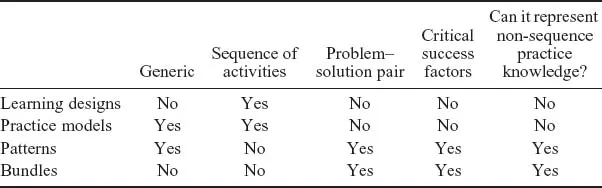

In a search for effective representations of intrinsic practices, we compare ‘practice models’ with two alternative representations, ‘patterns’ (Alexander et al. 1977; Dearden and Finlay 2006) and ‘bundles’ (Fincher et al. 2001). We discuss our experiences of using these on the Planet project, and with CETL ALiC. The relationship between the representations discussed in this article is shown in Table 1. The table shows which characteristics are necessary in the representations (though representations may display characteristics that are not necessary, for example some practice models may show problem–solution pairs, while some patterns may show sequencing information).

Table 1. Characteristics of different representations of teaching practice discussed in this paper. The table shows which characteristics are necessary for the representation to be classed as a representation of this type (though representations may display characteristics that are not necessary, for example some practice models may show problem–solution pairs while some patterns may show sequencing information). A representation showing a problem–solution pair has a form that states a problem and gives a solution to that problem; one showing critical success factors has a form that explicitly requires a statement of the conditions necessary if the solution is to be successful.

Practice models

Overview of the Mod4L models of practice project

The aim of the Mod4L Models of Practice project was to: ‘develop a range of practice models that could be used by practitioners in real life contexts and have a high impact on improving teaching and learning practice’ (Falconer et al. 2007, 2). The philosophy underlying the project was that a split in the e-learning community between technical developers, and research into how teachers can use technological tools most effectively, was impeding uptake of new tools and methods by teachers. To help overcome this barrier, and bridge the gap, a need was identified for teacher-focused resources that would describe a range of learning designs and offer guidance on how these might be chosen and applied; how they could support effective practice in design for learning; and how they could support the development of effective tools, standards, and systems with a learning design capability (see, e.g., Griffiths and Blat 2005; JISC 2006b). Practice models were proposed as such a resource.

Practice models were defined by the JISC as, ‘generic approaches to the structuring and orchestration of learning activities. They express elements of pedagogic principle and allow practitioners to make informed choices’ (JISC 2006b, 2).

However, as discussed above, the issue of representation of designs was central to the concept of sharing and reuse at the heart of JISC’s Design for Learning programme. Thus practice models needed to be both representations of effective practice and effective representations of practice. This article concentrates on the latter aspect – effective representations of practice.

The Mod4L project ran from May to December 2006. It took a teacher-centred approach, working in close collaboration with a focus group of 12 teachers to gather evidence on the usability of various forms of representation. Teachers were recruited across a range of disciplines and from both further and higher education in the UK, and were chosen from those who were known, from their participation in innovative projects or teaching award schemes, to be interested in changing their practice. Information was gathered from the focus group through two face-to-face workshops, and through teachers’ contributions to discussions on the project wiki (http://mod4l.com/tiki-index.php). This was supplemented by an activity at a JISC pedagogy experts meeting in October 2006, and a workshop at the UK Association for Learning Technology Conference (ALT-C) in September 2006.

The project defined five stages of sharing and reuse of a learning design: (1) browsing/searching a repository, (2) choosing a design, (3) developing/editing, (4) instantiation, and (5) reflection and feedback to repository; and evaluated nine different representational forms for usability in each of these stages (Falconer et al. 2007). The forms, chosen either because they appeared at the outset to be promising ways of representing learning designs to teachers, or because they were suggested by project participants, were:

(1) Case studies, for example the Otis case study collection (http://otis.scotcit.ac.uk/),

(2) Video case studies, for example the JISC Effective Practice guide (http://www.elearning.ac.uk/effprac/),

(3) Controlled vocabularies, discussed by Currier, Campbell, and Beetham (2005),

(4) Matrices/templates, for example the LDLite matrix developed in Littlejohn and Pegler (2007),

(5) Patterns, based on the architectural patterns of Alexander, discussed in McAndrew, Goodyear, and Dalziel (2006),

(6) Concept maps, discussed in Novak and Cañas (2006),

(7) AUTC temporal sequences, a graphical representation focusing on tasks, resources and supports (AUTC 2003),

(8) Flow diagrams, a graphical representation of a process using shapes and lines or arrows, and

(9) LAMS, an electronic learning system that enables teachers to plan and deliver technology-supported learning activities with a drag and drop interface (http://lamsfoundation.org/).

Among the main conclusions of the project were that questions of audience, community, and purpose are central to the effectiveness of a representation. Even within a single audience or community (teachers in this case), different representations are needed to meet different needs or purposes, and these needs change through a cycle of sharing and reuse.

Critique of practice models as representations of practice

Of the nine forms considered, the first two, case studies and video case studies, being heavily contextualised, are not candidates for representation of generic practice models. These contextualised representations are, however, the forms traditionally preferred by teachers when sharing innovative practice (Beetham 2001; Sharpe et al. 2004). This highlights one of the major findings of the Mod4L project, that while practice models might provide teachers with the information needed to orchestrate learning activities and resources, they generally fail to inspire them to change their teaching practice, possibly because of the lack of contextual information (Falconer et al. 2007; Falconer and Littlejohn 2008).

Returning to the initial definition of practice models, with the implication that these would support sharing, reuse and improved teaching practice, then they have at least three concurrent purposes. Practice models are expected to:

• Be generic

• Detail sequence and orchestration

• ...