![]()

Chapter One

Ecological Modernisation: Theory and Bangladesh

Economic development that is environmentally and socially beneficial is at the forefront of contemporary development debates all over the world. This is especially relevant in international trade where goods manufactured in least developed countries (LDCs) are being exported to developed countries (DCs) via international supply chains. The LDC exporters, workers and governments are participating in this trade regime to earn foreign exchange and fight their way out of endemic poverty. The DC importers and governments are encouraging these global supply chains to stimulate their own economies with goods that are of high quality, but produced at much cheaper rates than in their own countries. At the same time, consumers, governments and civil society in LDCs and DCs are concerned about the environmental and social impacts of these supply chains in sites of production and consumption. This concern is visible in the commodity chains for apparel (the garments industry), paper (the pulp and paper industry), coffee, bananas, chocolate (the food industry), etc., where product labelling is gaining prominence, starting from ‘fair trade’ stickers on coffee packets to ‘sweatshop free’ and ‘organic cotton’ labels on clothing sold in DC shops.

Accompanying this concern for environmental and social quality is the lively ethical trade debate, where well organised nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) in DCs and LDCs are working to bring to light issues of labour rights, working conditions and environmental resource degradation in LDCs as a result of globalised supply chains. The NGO debates are matched by a marked rise in the use of company codes of conduct (CoCs) by the product importers (DC retailers and buyers), which set conditions and standards that have to be met by the suppliers before goods can be shipped. Policymakers at both geographical ends are also actively seeking out ways to adjust to these new non-price trade conditions.

In our contemporary lives, the question of ethical trade touches us all, whether we are shopping for cotton t-shirts in the West or walking to work in a Vietnamese factory that produces hundreds of them everyday. What does ethical trade mean? What should it mean? What is our responsibility as the consumer? What is our responsibility as the factory manager? What are our expectations as workers and factory neighbours? Who has the right to decide these things? What are the different truths of ethical trade and whose voices carry these truths?

These questions remind me of the ancient Jain–Buddhist fable of the wise king who asked six blind courtiers to describe an elephant by touching it, the end result being much squabbling and determined insistence by the blind men that they each exclusively owned the truth. The wise king then said,

O how they cling and wrangle, some who claim

For preacher and monk the honoured name!

For, quarrelling, each to his view they cling.

Such folk see only one side of a thing.1

The reality of ethical trade debaters may be like that of the blind men — scattered all over the globe, we are only seeing partial views of the whole truth due to our geographical, cultural, economic and political perspectives, and our whole view of ethical trade is made up of these partial truths. None of us are necessarily right until we consider our perceptions in the light of an open and inclusive discourse. This book, in its small way, is an attempt to open half an eye to gauge the reality of ethical trade in supply chains.

The apparel supply chain is particularly vibrant in ethical trade debates, and this book looks at the Bangladeshi ready-made garments (RMG) industry as a case study. Bangladesh is the seventh-largest apparel exporter in the world (MFB 2007). The factories in Dhaka and Chittagong are facing demands for environmental and social management according to standards set by apparel buyers and consumers in environmentally progressive societies that may not find cultural or institutional resonance in Bangladesh (Huq 2002; Weist et al. 2003; Khondker et al. 2005). The firms are finding themselves in a situation of ‘institutional ambiguity’ (Hajer 2004), where there is little experience or precedent of green production in a reactive, technocentric, ineffective and change-resistant institutional set-up among both, firms and regulators.

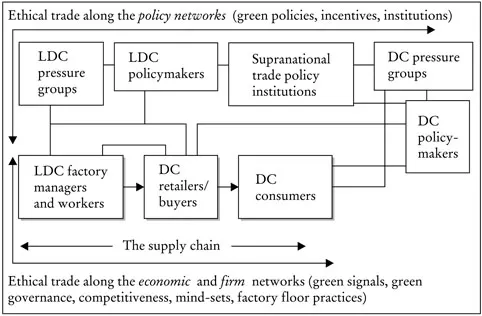

The problem is very complex (Figure 1.1) — it touches upon themes such as changing mindsets and practices at the level of the factory floor (firm networks); reliance on green supply chain signals (economic networks); and policymaking and implementation arrangements (policy networks). We also cannot ignore the basic principles behind the structure of the supply chain — constant pressures for cost reduction, on-time delivery and cheap labour in a highly competitive international market. It is interesting then, to question how ethical trade pushes these factories into greening to maintain market share in such a complex scenario. One way of looking at this problem is through the lens of the ecological modernisation (EM) theory.

Figure 1.1: Ethical trade in supply chains and the main influences

Ecological Modernisation Theory (EMT) and its Critics

Ecological modernisation refers to a group of theories based on the idea that economic growth can continue whilst ensuring environmental protection via long-term changes in the structures of production and consumption that emphasise proactive environmental management by society, market actors and the state. EMT arose in the 1980s as a reaction to the steady state and zero-growth ideologies of the 1970s, and in opposition to the Club of Rome’s ‘limits to growth’ argument. EMT architects (such as Huber, Jänicke, Spaargaren, Mol, Hajer, Weale and Simmonis) postulated that economic and environmental goals need not be in conflict with each other, and environmentally proactive economic growth can only help towards sustainable development. Needless to say, EMT is immensely influential in present-day discourses of development. For example, the UN World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED 1987) and various EU environmental action programmes, with their environmentally sustainable development rhetoric, designed to reorient fiscal and economic instruments towards technologies for resource efficiency, the internalisation of costs, waste minimisation strategies, longer product life cycles, etc., are resonant of EM principles (see Berger et al. 2001; Mol 1995, 1996, 1999; Rydin 1999; Hajer 1996; Toke 2001; Pepper 1999; Reitan 1998; Young 2000; Mol and Sonnenfeld 2000; Barry and Paterson 2004; Cater and Lowe 2000).

EMT was initially studied and empirically tested in industrialised countries in the mid-1990s. Since then it has broadened not only theoretically but also geographically to include less developed transitional countries (central and eastern Europe) and non-OECD countries (Canada and USA). The first stage heavily emphasised science and technological innovation in environmental modernisation. The second phase (from the late 1980s to mid-1990s) put less emphasis on technological innovations and took a more balanced perspective of the comparative roles of the centralised state vis-à-vis market dynamics. Since the mid-1990s the third phase has seen broader horizons in terms of geography (most significantly in Asia) and theoretical scope (including studies about ecologising consumption behaviour and global processes involving export-based firms; Mol and Sonnenfeld 2000).

EMT espouses renewed engagements with structural change and consequently, with modernity. It recognises the structural nature of modern ecological problems; the relationship between the environment and the structures of modernity need to become more benign via institutional change. Consequently, Spaargaren (1997: 3) describes EM as ‘a general theory of environment induced social change’, highlighting a view of multi-stakeholder involvement for creating capacity and incentives, that will lead to a network of institutions changing over time, including such geographically dispersed structures as global supply chains (Young 2000). EMT does not oppose modernity. Instead, it suggests that by rethinking the environmental crisis, we might find the impetus for social institutions to change from a reactive technocentric paradigm to a more proactive prevention-based paradigm, which will be the basis of a new engagement with modernity (Mol 1996). Theorists suggest, ‘solutions to the problems caused by modernisation, industrialisation, and science can only be solved through more modernisation, industrialisation and science’ (Buttel 2000a: 62). As Mol (1996) states, contemporary economic practices are deeply rooted in modernity and it makes no sense to imagine ecological production and consumption divorced from state institutions and modern science and technology. He suggests that economic processes be re-embedded with their ecological impacts within the existing institutions of modernity. Therefore, the two main assumptions of EMT are: first, in the words of Hajer (1996: 251), that ‘the dominant institutions indeed can learn and that their learning can produce meaningful change’, and second, that the ‘win-win’ goals can be attained through instruments of modernity.

Role of the Nation-State

EMT suggests a style of environmental policymaking where the regulators move away from a traditional command and control-based standard setting policy style, towards a more consensual, negotiation-based, decentralised policy style, using market mechanisms to change private sector behaviour. Berger (1999) calls this partial self-regulation with legal boundaries. This may be explained by Jänicke’s earlier work on state failure (1997), where he argued that given the different social spheres of development (the development of specialised knowledge and expertise, fast changing societies, post-modern institutions and the globalisation of markets) and the limitations of a state’s capacity to solve societal problems, the state should change to more participative and inclusive forms of governance. Pepper (1999: 6) refers to this as changing from a ‘curative and dirigiste’ style towards regulation that is akin to contextual steering. EMT’s normative side assumes a certain level of political modernisation (Jänicke and Weidner 1995; Berger et al. 2001; Sonnenfeld and Mol 2002) where citizens can express a preference for environmental quality and non-state actors (NGOs, research organisations, trade unions, etc.) are given the opportunity to contribute towards solving environmental problems, and assume traditional administrative, regulatory managerial and mediating functions. EM imperatives on policymakers do not end at changing policy styles: they have to design and facilitate the use of economic instruments (such as taxes, fines, subsidies and tradable permits) to monetise environmental protection by economic actors, and encourage proactive/preventative strategies by the private sector. Policymakers also have to realise the economic importance of strengthening green consumerism. Of course, behind these imperatives is the notion that multilevel stakeholders are genuinely convinced of greening and the distributive benefits of policy mechanisms are fair (Fisher and Freudenburg 2001). Analytically, pro-EM political modernisation can be seen in Europe with the trend of NGOs influencing environmental policymaking (e.g., Toke and Strachan 2006); increased civil society memberships in NGOs (Young 2000); and increased use of voluntary self-regulation mechanisms and eco-taxes for the private sector (Young 2000; Welford 2003), which means that the state is an important EM enabler (Berger et al. 2001). The nation-state is no longer the only level of analysis either; supra-level regional/international policymaking have become important aspects in addressing how the environmental impacts of a region or country inform environmental policymaking in international supply chains and globalisation; and EM studies in the age of globalisation cannot help but ask how much impact local environmental conditions have in that context of market economy environmentalism (Berger et al. 2001; Gibbs 1998, 2003).

Role of Market Actors

Economic actors are very much part of EM’s vision of modern institutions, not only because they hold together the modern phenomenon of globalised supply chains, but also because they are responsible for environmental degradation and remediation. Consequently, market actors (retailers, suppliers and consumers) ‘appear as actors for environmental reform, using mainly economic arguments and mechanisms to articulate environmental goals’ (Berger et al. 2001: 59). The normative vision of EM suggests that the economic actors will develop market advantage through the integration of anticipatory/preventative mechanisms into their production process. They have to recognise and internalise actual and anticipated costs of environmental externalities (perhaps reinforced via EM-driven economic instruments to be designed by the state actors) in company strategy making, which requires motivation, management skills and resources. Such motivation and incentive is meant to come from the market, legislation, and civil society preferences for a cleaner environment. Analytically, EM theorists link the reducing industrial pollution levels in DCs to the gradually increasing greening behaviour among Western companies and consumers as arguments for successful EM uptake among economic actors (Jänicke and Weidner 1995; Mol and Spaargaren 1993, 2002). The success indicators include numerous corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives, retailer CoCs for environmental management, environmental quality assurance certification schemes and the green technology options that can ‘leapfrog’ to LDC economic actors. Collaboration between private sector actors and civil society, NGOs, etc., is another aspect of successful EM. Most of these actions are not borne of private sector altruism but are driven by legislation, civil society protests and eco-awareness (McWilliams and Siegel, 2001). Motivating market actors remains a key challenge in operationalising the normative aspects of EMT.

Role of Science and Technology

Science and technology are highly valued in EM because of their role in the refinement of production (e.g., use of green technology to achieve highest possible environmental standards, use of anticipatory mechanisms, resource use minimisation, etc.) and consumption (e.g., life-cycle analysis, recycling and reuse). According to Weale (1992: 76),

Since environmental amenity is a superior good, the demand for pollution control is likely to increase and there is therefore a considerable advantage to an economy to have the technical and production capacity to produce low polluting goods or pollution control technology.

Instead of being judged for their role in creating the environmental crises, science and technology are highly valued in EMT for creating the basis of proactiveness (Blowers 1997). The normative EMT suggestions depend on the availability and ability of technology to deliver a win-win ecology–economy synergy by providing resource efficient methods of producing goods, while keeping costs down and profit levels up. This is especially pertinent in pollution intensive sectors such as paper, pulp, palm oil, etc. Another key challenge of EM remains the availability of expert knowledge, ease of learning and the actual adoption of green-technology/practices at the level of non-expert practitioners (Sarkis 1999), especially in LDCs. Therefore, along the supply chain, questions arise regarding the necessary conditions behind the availability, quick transfer and acceptance of green technology and green management mechanisms.

EMT is both a normative theory, prescribing desirable solutions for structural change, and an analytical–descriptive theory that identifies how modern societies construct the environment and analyses the nature of social and policy dynamics (Gouldson and Murphy 1997; Blowers 1997; Christoff 1996; Mol and Sonnenfeld 2000). At a practical level, these aspects often merge, and proponents have used EMT for both purposes, which is also the approach taken in this book. This approach is useful in delineating the contradictions between the normative and the analytical dimensions — it helps illustrate why and how a given EM situation may be only partially ecological.

Some Criticisms of EMT

EM has elicited much criticism from various corners, foremost among them the Neo Marxists, radical environmentalists and post-modernists (Buttel 2000b; Toke and Strachan 2006). Broadly, they disagree with EM’s theoretical assumptions by saying that its technocratic solutions, economistic arguments, and reliance on Western-dominated market systems justifies the Western-style status quo by hindering more radical approaches to sustainable development (Pepper 1993; Yearley 1994; Christoff 1996, 1997; Dobson 1990; Seippel 2000).

An important criticism comes from Christoff (1996: 486), who suggests that in its most common forms EM is reductive, technocratic and corporatist:

Given this dominant emphasis on increasing the environmental efficiency of industrial development and resource exploitation, such EM remains only superficially or weakly ecological. Consideration of the integrity of ecosystems, and the cumulative impacts of industrialisation upon these, is limited and peripheral.

Christoff, along with Berger et al. (2001) and Harvey (1996), criticise EM for giving insufficient emphasis on ecological protection. They suggest that such economistic discourse dresses environmentalism into the language of business, and gives licence for ‘greenwash’ and ‘politicians’ puff’ (McWilliams and Siegel 2001: 112). EM’s assumptions that existing structures and relationships between the state and the private sector can meaningfully internalise ecological considerations, are seen by Neo-Marxists as celebrating contemporary capitalism with a green paint job, a criticism that is also raised by different shades of t...