![]() Part one

Part one

Historical and Theoretical Background![]()

Chapter one

A history of MNE activities in Latin America

Introduction

Sources of external finance in Latin America

The major form of MNE business, that is foreign direct investment (FDI), began long before the independence of Latin American countries from European colonial powers. Spanish and Portuguese individuals and firms owned a variety of investments — such as farms and raw materials ventures — in the Latin American colonies before 1800.1 In order to make the task of this chapter manageable, the story will be taken up just after the region's independence wars, that is in the early 1800s. This introductory section offers an overview of long-term investment in Latin America during the period up to the Second World War. Subsequent sections look in more detail at the activities of British and American firms in the region from 1820 to 1980. The final section discusses MNEs from other countries operating in Latin America since the Second World War, and then offers some conclusions concerning trends in MNE activities and in government-business relations. Discussion of the 1980s is left for Chapter 3 and subsequent chapters that focus on specific MNE-related business issues in the region.

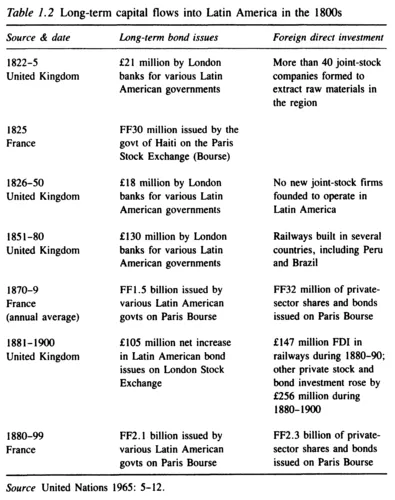

The colonial period in Latin America largely came to an end in the first two decades of the 1800s, when Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Peru, and several other countries won their independence from Spain, or in Brazil's case, from Portugal. The earliest major form of long-term capital flow into Latin American countries was the purchase of bonds issued by Latin American governments soon after their independence battles. Most of these purchases (of about £20 million in value) were made by British merchant banks and other financial intermediaries in the London market. In addition, some direct investment (of about £4 million in value) took place in companies established to explore for gold and silver in former colonies such as Mexico, Peru, and Chile.2

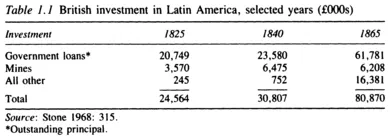

The bonds were issued in the London financial market by investment banks on behalf of Latin American governments, which in turn used the funds largely to pay for war debts incurred previously. The bonds were quite speculative, selling at substantial discounts under face value and paying high rates of interest. When the Latin American governments became unable to service their interest payments by the late 1820s because of inadequate export earnings, the market for the bonds collapsed and remained inactive for over two decades. (The parallel with the 1980s is quite striking, if for 'government bonds' we read 'sovereign debt' to commercial banks!) Similarly, the investments in mining company shares were largely lost to bankruptcies, though a few of the mines continued to produce ores profitably for many years.3 It was not until the Industrial Revolution began to spread to Latin America that a new wave of investment entered the region. Table 1.1 sketches the early British long-term investments, both loans and stock/bond purchases. Government loans remained stagnant until the 1860s, with primarily refinancing of defaulted loans as the main area of increased lending. Investment in mining ventures actualy grew during the 1825-40 period, despite the bankruptcies, and then declined until 1865. In fact, the real growth in investment came from the arrival of the Industrial Revolution.

By the 1850s the advent of railroads and telegraph led to major investments in Latin America, again primarily from the United Kingdom. Both loans to national governments (in the form of bond issues on the London Stock Exchange) and direct investment in the railroad and utility companies increased British investment in the region substantially. Britain's leadership in the Industrial Revolution gave British firms the competitive advantages that could be exploited through direct investment, contracting with local firms, and otherwise transferring the industrial knowledge gained in the United Kingdom to Latin America. While the early direct investments primarily served the local market needs for transportation and communication, they also later served to facilitate dealings with foreign purchasers of raw materials and suppliers of imports — as well as enabling MNEs to communicate with local affiliates more easily and efficiently

It should be recognized at this point that most of what is being termed 'direct investment' in the nineteenth century was quite different from the common perception of this activity in the period since the Second World War. In the nineteenth century much of the direct investment that entered Latin America was indeed undertaken by British joint-stock companies, but these firms were generally formed by risk-taking investors to support the entrepreneurial efforts of a few British expatriates who emigrated to the New World. These expatriates, in turn, hired local workers and built local companies to operate railroads, telegraph companies, and mines in Latin America. Thus there was not a transfer of knowledge and skills that is typical of the modern MNE, but rather a transfer of funds that enabled British entrepreneurs to start essentially new firms and operate them. In terms of ownership, the investment was in fact direct. In terms of control, while it is true that the Europeans controlled the purse strings, it is more accurate to say that operating control tended to rest with the expatriates in Latin America. This is significantly different from the 'multinational enterprise' type of foreign direct investment that occurs today, when domestic and foreign activities are (at least somewhat) integrated parts of a total firm. [This point was suggested by Mira Wilkins, who graciously reviewed the present chapter.]

Overall, the picture of long-term capital flows (direct and portfolio investments) to Latin America during most of the 1800s showed primarily British participation, and was dominated by lending to governments through bond issues and direct investment rather than commercial bank lending or government lending. The United States was a minor factor in the capital flows until the end of the century, and indeed the United States still was a net borrower in international financial markets during that period. Table 1.2 depicts some of the broad characteristics of investment in the nineteenth century.

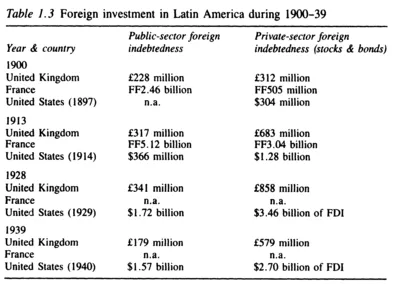

By the turn of the century, the nature of foreign investment in Latin America was moving more toward the private sector and away from government bonds. Bond sales in the London market still remained substantial, but the issuers were railways, mining companies, and other private-sector firms. Direct investment had become predominant in relation to the portfolio investment in bonds for British investors. Investors from the United States also were placing much more of their funds into direct investments. In 1908 the stock of US investment in the region included $334 million of portfolio investment and $749 million of direct investment (primarily in railroads and mining).4 (Foreign aid, another source of foreign financing that typically figures in twentieth-century measures of foreign capital entering Latin America, was virtually nonexistent during the period up to the Second World War.)

As the twentieth century began to unfold, the United States gamed in industrial power relative to the United Kingdom. In Latin America

this meant that US lenders (bond purchasers) began to replace British ones, and US direct investors began to seek out raw materials' supplies in the region. By the end of the 1920s, US capital flows exceeded British flows to Latin America, and the total stock of investment had become predominantly American. Direct investment outweighed portfolio investment from both sources. Estimates of the external financing from both countries in the early twentieth century appear in Table 1.3.

Countries of origin of capital flows to Latin America

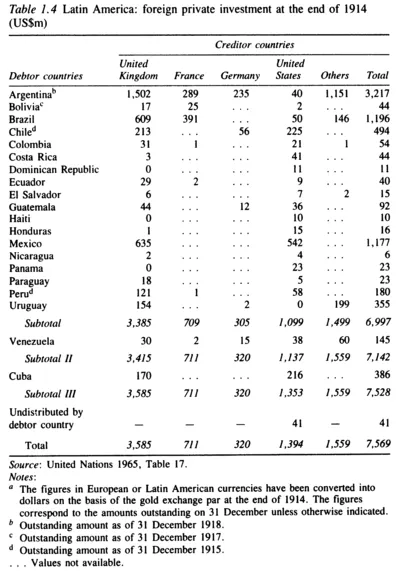

The United Kingdom and the United States were the sources of at least two-thirds of long-term capital flows to Latin America during the entire period up to the Second World War. As already noted, the United Kingdom was the first major creditor country to Latin American nations that won independence from Spain or Portugal in the early 1800s. During the entire century, UK investors played the largest role in external financing of Latin American economies and in the transfer of industrial knowledge through foreign direct investment.

France, Germany, and the United States subsequently increased in importance as suppliers of foreign capital (and knowledge) to the region. By 1914, US firms, individuals, and governments had become major investors in the region, surpassing all source countries except the United Kingdom. Table 1.4 gives some details concerning the distribution of investors and recipients of foreign direct investment stocks in 1914. Note the heavy concentration of investments in the three largest countries (Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico) and the dominance of British and American investors overall. French direct investment was concentrated in Argentina and Brazil at that time, and it far exceeded US investments in those countries. In contrast, US investment was much heavier in neighboring Mexico, and in Central America. UK investments were located much more in South America and particularly in Argentina. Not only did British investment dominate the total (at close to 50 per cent), but this was a major part of total British overseas investment at the time. The $US3.6 billion total British long-term investment in Latin America was approximately the same magnitude as total British long-term investment in the United States.5

After the First World War, European investment in Latin America diminished greatly as the Allies rebuilt their own economies from war damages, and Germany had many investments confiscated by national authorities in the region. US investment increased somewhat, but it appears that total foreign investment in Latin America decreased from 1914 to 1929. The US share increased from about 17 per cent of total foreign long-term capital in 1914 to about 40 per cent in 1929.6

During the Depression of the 1930s, very little new foreign investment entered the region. External debt throughout the region was defaulted beginning in 1931, and so new bond issues in New York or London were not viable. This debt crisis was due partially to what in retrospect appears to be overborrowing during the late 1920s and partially to steep declines in the prices of Latin America's main export commodities: sugar, copper, precious metals, and petroleum. The stock and flows of foreign direct investment declined as well, due to diminishing market capacities of the countries and also to increased restrictions on the transfer of earnings abroad.

The Second World War brought with it an increased demand for Latin America's commodities, especially by the United Kingdom and the United States. This stimulus to exports, and a much slower increase in importing, led to favorable balance-of-payments positions for most of the countries of the region during the war. Given the industrial countries' war efforts, however, the improved economies in Latin America still did not attract noticeable increases in foreign investment until after 1945.

Target industries of foreign investment in Latin America

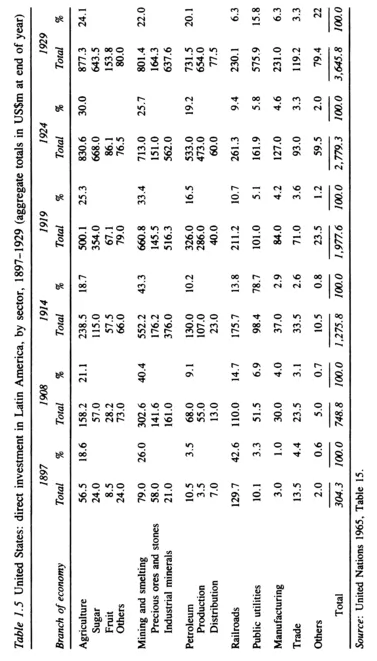

Throughout the first 150 years of post-colonial experience in the region, foreign investment was concentrated in natural-resource industries and public utilities (e.g. power generation, telephone and telegraph service, and public transportation). Construction and operation of railroads in the mid-1800s attracted both foreign debt and equity investments which far surpassed any other industry. By the end of the century, in both US and UK direct investments, railroads accounted for about half of the total. Additional targets of British investment included public utilities and banking, but the combined shares of these industries in total British investment never exceeded 10 per cent. Direct investment by the US firms showed a rapid decline in railroads after 1900, and increased shares of mining and agriculture. Table 1.5 shows the sectoral distribution of US direct investment form 1897 to 1929. Note that by the time of the Depression, US direct investment had shifted to sugar, oil, mining, and public utilities (especially telephone companies, that ITT and other US firms took over when British firms divested). Railroad investment was

minimal by 1929, and indeed it continued to decline subsequently. In all of these industries except railroads, the foreign firms were able to compete on the basis of their ability to obtain large amounts of capital and their access to large foreign markets to sell the raw materials.

During the Depression, total US direct investment in Latin America fell slightly (from a total of about $3.5 billion in 1929 to about $2.7 billion in 1940), and its sectoral distribution changed significantly. Declines in agriculture and mining were offset by increases in petroleum and manufacturing. In the railroad industry (as well as in several ot...