![]() INTERNATIONAL MODELS OF MENTAL HEALTH SYSTEMS FOR CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS: WHAT IS THE REALITY WHEN WE PUT PRINCIPLES INTO PRACTICE?

INTERNATIONAL MODELS OF MENTAL HEALTH SYSTEMS FOR CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS: WHAT IS THE REALITY WHEN WE PUT PRINCIPLES INTO PRACTICE?![]()

20

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry in France

COLETTE CHILAND, PIERRE FERRARI AND SYLVIE TORDJMAN

In this chapter, we address questions concerning the training of child and adolescent psychiatrists and of practitioners in related professions. Then, we present the diverse types of public and private practice in child psychiatry, as well as the theoretical orientations prevailing in France. Finally, we give some indications regarding research in child psychiatry.

TRAINING OF PSYCHIATRISTS

In France, psychiatry separated from neurology after the events in May 1968. Prior to this, both fields belonged to “neuropsychiatry.”

Child psychiatry represents a specialization of general psychiatry. It is taught through an additional option in the psychiatry curriculum.

Generally, it is therefore impossible to practice child and adolescent psychiatry unless one has acquired the qualification to be a psychiatrist. Yet, recently it has become possible for pediatricians to obtain a degree in child psychiatry (which does not involve becoming a child psychiatrist) if they have completed certain courses and internship requirements during their internat (residency).

Access to training in psychiatry is through the internat at the Centres Hospitaliers Universitaires (C.H.U., University Hospital Centers). The internship begins with a competitive examination at the end of the medical curriculum, which can be taken only twice. It gives access for 4 years to positions of responsibility in specialized services in which the intern can acquire the qualification of psychiatrist. The child psychiatry option can be granted to interns who have the qualification in psychiatry if they have also spent four semesters of their internship in services qualifying for child psychiatry and regularly attended a certain number of seminars which fulfill the child psychiatry requirements.

Thus, recruitment of psychiatrists as child psychiatrists in France is carried out through a competitive examination (considered as both democratic and very selective).

This examination evaluates candidates more for their abilities to learn and to memorize a great amount of information than for their clinical abilities, their creativity, and their motivation to get involved in the field of psychiatry.

For a period of time, long ago, there was a specialized internship in psychiatry that one could enter if one had an inclination toward psychiatry. This is not the case today, and it can happen that candidates choose psychiatry based on their rank for the internship, regardless of personal interest in psychiatry.

Because child psychiatry is not in itself considered as a specialty, theoretically, any medical doctor specialized in psychiatry can practice child and adolescent psychiatry. Actually, in most high-ranking positions offered in child and adolescent psychiatry, it is generally required that candidates have completed the additional option for the title of child psychiatrist. Yet the majority of French psychiatrists support more versatility in psychiatric practice to avoid compartmentalization between general and child psychiatry.

TRAINING OF ALLIED PROFESSIONALS

Besides private practice, work in child psychiatry is the result of a multidisciplinary team. Associated with psychiatrists, we find psychologists, speech therapists, diverse educators, psychomotor specialists, social workers, and nurses.

All these professionals, except psychologists, are trained outside of universities, in specialized schools into which candidates can enter after their high-school degree. Currently, these short training periods tend to be 1 or 2 years longer than before, for a total of 3–4 years of schooling. The training acquired in these schools is most often multipurpose. It occurs mainly through daily work in child and adolescent psychiatry departments so that these professionals become competent in child psychiatric disorders.

Psychologists are trained in universities for 5 years. During their final year, they can specialize in child and adolescent psychology. Only a psychology degree with training in clinical and abnormal psychology theoretically allows one to work in child and adolescent departments.

In France, these allied professions have a lower economic status than in other European countries (United Kingdom, Scandinavia, etc.) or in the United States.

CHILD PSYCHIATRY CLINICAL PRACTICE

A number of practitioners work in both the public and private domains. Some of them practice in only one domain. Public sector care in child psychiatry is well developed in France. In 1972, the government created child and adolescent psychiatry sectors. The main goal of the child psychiatry sectors was to carry out, in their geographical areas, the entirety of the preventive and treatment activities concerning child and adolescent mental health.

Thus, the child and adolescent psychiatry sector is in charge of:

1. A complete psychiatric examination of the child, if necessary, psychological, speech, and psychomotor evaluations, and even a school assessment. This examination includes a thorough interview with the parents.

2. The treatment of the child, if necessary. Theoretically, every type of therapeutic action can be carried out within each sector: therapeutic consultations, family guidance consultation, or more frequent and more regular therapy (psychotherapy, speech therapy, psychomotor or educational therapy) individually or in groups.

All the therapies proposed within the sector are free and are performed as close as possible to the families’ homes.

Psychiatry sectors are in close contact with the other agencies dealing with childhood: mother and child protection agencies, public healthcare centers, day-care centers, schools, child social work family court, and childcare services in hospitals. Concurrently, the psychiatry sector is developing a series of training, teaching and research programs that will contribute to setting up primary prevention. The team in charge of these preventive actions is multidisciplinary. The multidisciplinarity is based on significant work done during clinical and administrative meetings.

Sectors may have at their disposal five types of facilities for performing treatments. However, not every sector has all the existing facilities available. The five types of facilities are listed below.

Centres Médico-Psychologiques (Medical Psychological Centers). Outpatient consultation and treatment centers, which are the bases of operation of the coordinated activities.

Daycare Hospitals. Institutions in charge of children with serious mental disorders during the day, providing intensive treatments as well as the necessary educational programs (the latter are carried out by special education teachers from the public education system).

Part-time Therapeutic Centers. Institutions in charge of therapeutic treatments for a number of hours each day, while allowing the child to stay in the regular school system; this facility is for less serious cases.

Full-Time Residential Treatment Centers. For long-lasting psychotic pathologies, residential treatment is justified by the seriousness of the illness or by family disorganization. For more acute pathologies, particularly with adolescents (depression, suicide attempt, anorexia nervosa), shorter confinements are possible, allowing the implementation of a therapy that can be continued after leaving the hospital.

Therapeutic Family Placement. The patient is placed in a family setting for children with psychiatric disorders through assistance paid for by the hospital and supervised by a sector’s specialized team.

Some public or semipublic healthcare units working in the field of child psychiatry are nevertheless independent from child psychiatry administrative structures. These are mainly:

The Centres Médico-Psycho-Pédagogiques (CMP: Medical-Psychological-Educational Centers). These are managed by nonprofit, private associations. The CMPs have done pioneering work in ambulatory treatment of children with psychological disorders and difficulties in school. They function within the same framework as the child psychiatry structures and represent an important part of the child psychiatry care system.

The Centres d’Action Médico-Sociale Précoce (CAMSP: Early Intervention Medical-Social Centers). These aim at taking care, very early on, of the special education and treatment of preschool children with somatic disorders, and motor, sensory or mental handicaps. The CAMSPs can be multipurpose or specialize in treating a specific handicap. They propose the treatment and remediation required by the child’s condition/state which can be performed in groups or individually, at the center or at home.

The Instituts Médico-Éducatifs or Médico-Pédagogiques (Medical-educational Institutions). Managed by nonprofit private associations, they provide, under medical supervision, educational and pedagogical activities with children who generally have a mental deficiency, sometimes associated with psychotic disorders or a physical handicap.

THEORY

Psychodynamic approaches (from psychoanalytic theories) continues to have a large influence on the majority of child and adolescent psychiatrists. Hence, this influence can be found on the psychological approach, remediation, institutional work, individual or group therapy, or work with the family, all of which are favored in child therapy. Pharmacological treatments have only a limited use. For example, the use of Ritalin today remains rare.

The classification used to fill out the diagnostic forms is the Classification Française des Troubles Mentaux de I’Enfant et de I’Adolescent (French classification system). However, the OMS ICD CIM 10 classification and sometimes the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual) are also used for international publications.

RESEARCH

The sectors’ budget does not mention research funding. Funding has to be found from other sources, such as the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, or organizations that can support research or lead research networks in child psychiatry.

OFFICIAL ORGANIZATIONS

The Société Française de Psychiatrie de I’Enfant et de I’Adolescent et des Professions Associées publishes a journal, Neuropsychiatrie de I’Enfance et de I’Adolescence. In addition, there are other publications concerning child psychiatry such as Psychiatrie de L’Enfant, Journal de la Psychanalyse de I’Enfant, and Revue adolescence.

CONCLUSION

French child psychiatry is characterized by (a) its sectored network of care structures implemented in the whole country since the 1970s, (b) with its completely free healthcare, which can therefore be available to the most underprivileged (these public services are financed by Social Security), as well as (c) its psychodynamic approach, which supports understanding and treatment of the psychiatric disorders of children and adolescents.

![]()

21

Approaches to the Development of Mental Health Systems for Children in the Nordic Countries

HELGA HANNESDÓTTIR

OVERVIEW OF CHILD AND ADOLESCENT PSYCHIATRY IN THE NORDIC COUNTRIES

The Status of Children

The history and roots of child psychiatry go back almost 250 years, yet the development of specific services for child psychiatry is much more recent, beginning only about 27 years ago in Iceland. The European Union of Medical Specialists (EUMS) has recently acknowledged child and adolescent psychiatry/psychotherapy as a main specialty in medicine. For decades, the main emphasis in the development of child psychiatry in the Nordic countries has been on promoting clinical services.

All the Nordic countries are divided into healthcare districts. Except for Iceland, in each district there is a central hospital for specialized healthcare with a child psychiatric service for in- or outpatients or a child psychiatrist who sees children on a consultative basis. In most districts there are child guidance clinics that belong to either the social service or healthcare sectors. Due to the current economic recession, profound changes are taking place in Sweden, Norway, and Finland to decrease the cost of services in child psychiatry. One day in the hospital for child psychiatric care can cost around four times the amount for adult psychiatric services, which has aroused interest among clinicians in the effectiveness of child mental health services.

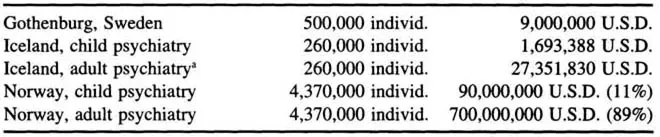

There are many similarities in the five Nordic countries, yet many differences exist as well. Total budgets for child psychiatric services vary greatly within and between the countries (Table 21.1). In all countries, medical treatment is socialized and care at hospitals is free for children and adults. Taxes are high: 35% to 63% depending on income, with Denmark presently having the highest rate. Acute medical care is excellent, the infant mortality rate is low, and longevity is high. But many of the needs of children and adolescents with mental problems have not been met, especially in Iceland. Child psychiatry must utilize its knowledge of the etiology of mental disorders to promote the health of children and must strengthen the capacity of families and communities to reduce the incidence and prevalence of substance abuse and mental health disorders in later life. Linkages of mental health specialists with schools, the police, social service agencies, and the juvenile courts has begun to provide an important contribution toward improving the interorganizational networks.

Table 21.1 Total Community and State Budgets for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry in 1995 in Gothenburg, Norway, and Iceland

Family life has changed during the past two decades in all Nordic countries. Live births have decreased. Legal abortions, the divorce rate, and the urban population have increased. The number of children living with one adult and the number of women who work outside the home have increased markedly. The accident rate among children in Iceland is very high, and there is an increase in the suicide rate for adolescent boys between 15 and 24 years in both Finland and Iceland. Immigration into Sweden has been the highest among the Nordic countries in recent decades, and over 70 languages are spoken in some Swedish public schools.

Clinical Services

All countries have general service programs in child and adolescent psychiatry, but recently there has been much discussion about the coordination of services. The need for child psychiatric beds has been estimated to be about 4 beds per 10,000 children. There is an increased tendency to look at prevention and treatment of mental disorders of children as an issue of general public health.

The university chairs were established in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The number of specialists (Table 21.2) in the discipline varies, according to the population in each country, which is from 5 to 7 mil...