eBook - ePub

The Personnel Managers (Routledge Revivals)

A Study in the Sociology of Work and Employment

This is a test

- 246 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Personnel Managers (Routledge Revivals)

A Study in the Sociology of Work and Employment

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

First published in 1977, this Routledge Revival is a reissue of the first comprehensive sociological study of the role of the personnel manager, which considers both the individual experience of the person working in this field and the role the occupation plays in the management of employing organizations. In the process of studying the individual experience and the organisational and social contributions of personnel managers, the book represents a step towards a sociology of work which draws on and contributes to the mainstream of sociological theory.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Personnel Managers (Routledge Revivals) by Tony Watson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Human Resource Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1 The Sociological Framework

The academic discipline of sociology and the practical activity of personnel management can both be seen as having developed as responses to major historical changes. These are changes associated with the processes of industrialisation and modernisation. But sociology and personnel management are not only responses to societal changes: each is itself now a part of that world which has come into being with the growth of large-scale industrial capitalist organisation in the West. The two phenomena are very different in nature but each can be understood in part as an attempt to come to terms with the human problems associated with a particular social order. Nisbet (1970) has shown how nineteenth-century sociology involved theoretical efforts to reconsolidate a European order which was being dislocated by forces emanating from the French and Industrial Revolutions. The problems with which the classical sociologists dealt are to be seen ‘in the almost inevitable contexts of the changes wrought on European society by the forces of division of labor, industrial capital, and the new roles of businessman and worker’ (ibid., p. 24). The contexts in which sociology grew are those which presented practical problems to the men building the new order, the order to which the sociologists can be seen as partly in reaction. The moral concerns and the interests behind the activities of those practical men are quite distinct from those of the sociological thinkers but to a significant extent the development of personnel management was a way of engaging with some of the same set of problems.

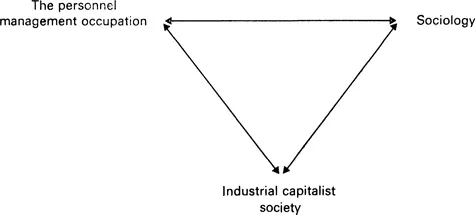

This study is not simply a sociological examination of the attitudes and practices of those engaged in the activities covered by the heading ‘personnel management’. It is, rather, an attempt to study these activities and the experiences of those carrying them out in the context of a particular type of society. The aim is, then, to add to the understanding of both the occupational activity of personnel management and the industrial capitalist society of which it is a part. But, in this study, the discipline of sociology is not simply the instrument through which these two aims are to be fulfilled. A third aim of the study is to contribute to the discipline of sociology itself by paying close attention to the problems and potentialities of the discipline, with particular reference to the study of the world of work and employment. The three major foci and their relationships can be represented diagrammatically as in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1

The concern behind this chapter is the nature of sociology itself and the more specific aim is to construct the sociological apparatus which will be used throughout the study. The theoretical and methodological discussions which follow are not to be seen simply as some sort of preamble; the desk-work which precedes the real research. These deliberations are an integral part of the researcher’s experience, both as an empirical observer and as a reader of books. To clarify what is seen as an essentially dialectical relationship between research and theories, on the one hand, and the researcher and his theories and generalisations on the other, I shall introduce at this point the notion of reflexivity.

Reflexive Sociology

The idea of a ‘reflexive sociology’ was introduced in Gouldner’s widely discussed analysis of a coming crisis in Western sociology (1971). A reflexive sociology is proposed as a way of dealing with the fact that sociologists’ theories are ‘not the product of “immaculate” theoretical conception’ and are ‘not only the product of a technical tradition, of logic or of evidence, but of their whole social existence’(Gouldner, 1975, p. 148). Gouldner’s new sociology appears to be dependent upon the willingness of sociologists to build new com-munities and institutions which will ‘provide the social basis for the natural emergence of various new theories’ (ibid., p. 95). The interest in reflexivity in this study is one with far more modest intent than Gouldner’s, and I would argue that it may not be appropriate for all sociologists to go about ‘creating theoretical collectivities for rational discourse by social theorists’ (ibid., p. 78), particularly if one way of advancing knowledge of social life is believed, as it is here, to be through the researcher’s involvement in the everyday lives of non-sociologists. A more useful discussion of a possible reflexive sociology is that of Dawe (1973). His version utilises and makes explicit the relevant experience of the sociologist but takes us beyond the level of the personal experience with its inherent danger of individualistic subjectivism and navel-gazing1 by stressing the requirement for the experience which is drawn upon to be representative experience. This is valuable in that it takes account of Wright Mills’s notion of the sociological imagination with its analytical distinction between the individual and the social structural (Wright Mills, 1970) and recognises that the sociologist is himself linked into the same social structure as are those whom he is studying and those for whom he writes:

The representative experience goes beyond the particular, localised, albeit intersubjective experience. It articulates the connection between the latter and the major currents of social and political concern, between the personal trouble and the public issue. Quite simply, to have any impact on social, political or any other form of public thought and action, the particular must stand for the general (Dawe, 1973, p. 35).

This conception of reflexivity is taken up in this study to enable the reader to make better sense of my theorising activity and to enable him more easily to evaluate both my own reporting and interpretations by revealing to him something of my self, the nature of my involvement in my research settings and, most importantly, the value positions and the structure of sentiments which are behind the accounts which make up this volume. If the reader of a sociological study can see something of the way that the sociologist generally fits into and interprets the world which they both, to varying extents, are bound to know, then he can more effectively decide which of the findings to assimilate into his own understanding of the world and which to reject. The assumption is being made here that sociology cannot be value-free. It must therefore be incumbent upon the writer to reveal to his audience his value position for two reasons. First, one’s values cannot be stated briefly in a few introductory comments or summarised in an appendix, and second, they are a part of one’s self and experience, so the sociologist’s value stance must be brought from the background into the foreground. This is particularly important in a study like this, where the author has closely involved himself with the activities of those whom he is studying.

To meet the requirements of a reflexive approach and to give my readers the requisite insight into the background and the value basis of the study, I shall do several things. One of these is to indicate the experiential background to both the theorising process and the various forms of involvement in the milieu under examination. Another is to reveal, in the course of developing the theoretical scheme which provides the framework for the study, what Gouldner calls the theorist’s background assumptions (1971, p. 29). In revealing the ‘world hypotheses’ and ‘domain assumptions’ which make up the assumptions on which the more specific ‘postulations’ are based and by providing some biographical context to indicate the ‘sentiments’ to which these assumptions relate, I hope to assist the reader in his evaluation of the work. I shall deal first with the experiential background but must, before I do this, take note of some important observations which have been made about the relationship between the theorist and his theories.

Blum has argued that theorising is a ‘self-transforming operation, where what one operates on is one’s knowledge of the society as part of one’s history, biography, and form of life’ (Blum, 1971, p. 313). Without accepting the full implications of Blum’s overall position2 the insights here are taken to be valuable and indicative of the need to relate, or to enable the reader to relate, the theorist’s and the audience’s experience of the world under review. As Blum argues

As a user of language and a follower of rules, the theorist is simultaneously addressing self and community, for the self is essentially public and the community is part of his self (part of his history, his biography, his corpus of knowledge) (ibid., 1971, p. 308).

Although the detailed work which makes up the bulk of this study was done from a relatively conventional position in an academic institution, a large part of the underlying theorising work was done whilst I was employed in industry. Many of the orienting questions and ‘hypotheses’ about the personnel occupation as well as a large quantity of informal ‘data’ originated during this period of my biography. This fact, combined with the inevitable suspicions which are aroused by any sociologist’s close involvement in his research milieu, make it incumbent upon one, it is felt, to give some detail of this experiential base. Although I believe that Glaser and Strauss (1967) underestimate the extent to which any researcher, explicitly or otherwise, brings prior theoretical orientations to his research work, I do accept many of their criticisms of ‘logically deduced theory’ and wish to see the generation of theory ‘grounded’ in the process of research. I go further than Glaser and Strauss, however, and argue that as one’s researches and one’s theorising are parts of one’s self then one must locate them in their biographical context.

The Experiential Background

Like many other sociologists I found my way onto a first degree in sociology by way of a working-class upbringing and a grammar school. The study of sociology gave an opportunity to formalise a fascination with making theories about the social world which went back to my early childhood when I first became aware of class differences and differences between English and Scottish cultural patterns. As an undergraduate I became highly attached to sociology and was attracted to it as a way of life. The area of industrial sociology was particularly engaging given a powerful drive on my part to learn about the factory life experienced by my father. It was this particular concern, combined with a reluctance to continue life on a grant, that turned my attention towards industrial employment. My suspicion that the literature of industrial sociology did not always effectively engage with the realities of industrial life and rarely ‘got inside’ industrial organisations, and particularly ‘inside’ management, added to the resolve. The choice of work in the industrial relations sphere is especially important here because, as will become apparent later in the study, I am here revealing myself as following a pattern shared with some of my respondents – to put it crudely at this stage, what might be seen as other than ‘managerial’ sympathies among those in industrial relations work, at least in the early stages of the career, is not untypical. I attempted to retain my academic identity by registering for a part-time research degree at a local university, something which would systematise my learning about the industrial world and provide me with a passport back to academic life at a later stage.

During the three years spent in the engineering industry I became involved in most of the aspects of personnel management, but specialised in industrial relations. My involvement, in this work, together with a recognition of the very quickly growing importance of the personnel function within management and some experience of the would-be professional body (the Institute of Personnel Management), sowed the seeds of interest in what has become the present study. The research work which I did at the time, however, was on sociological aspects of organisational change (Watson, 1972). But the greatest advantage of this particular setting for doing sociology was, I believe, a more general one. It enabled me to ground all my thoughts about sociological theory and methods, the ‘relevance’ of sociology, the utility of existing studies and so on, in a setting of ‘active social relationships’.3 I found the industrial setting of value as a sort of laboratory in which to investigate issues of major interest in sociological theory. As I have put it elsewhere,

In complex industrial organisations we can see with more clarity than in many other settings what has been called the ‘dialectical interplay between human striving and social constraint’ (Rex, 1974, p. 4) as individuals and groups articulate and play out conflicts of interest; structures and strategies are devised in processes whereby power is wielded and resisted, and life chances of participants (and indirectly their families) are both reflected and created (Watson, 1976a, p. 1).4

It was in thinking about sociology on a day-to-day basis whilst being intimately involved in the ongoing practical issues of organisational life that I developed the theoretical scheme which is to be set out shortly and which is to provide the framework of this study. The theoretical scheme as it now stands has been developed and reformulated throughout my subsequent few years as a full-time academic, in the light of further reading and, more particularly, through its use in teaching sociology to a range of students.

I now wish to set out the considerations and criteria upon which the theoretical scheme is based. I must, however, point out that these criteria are at the same time partly conclusions of the same theoretical process. It is difficult to do justice to the dialectical relationship between research and theory; the process of writing down an account of one’s theorising does tend to suggest an apparent but unreal process of development.

The Subdivisions in the Sociological Study of Work

One of the criteria behind the devising of the theoretical framework for this study is that it should facilitate the breaking down of the divisions which exist between the sociological study of the various aspects of what men and women experience in their involvement in work. The artificiality of these divisions became a matter of considerable concern to me as I reviewed the relevant sociological literature with a view to bringing its perspectives to bear on my earlier research work in the industrial plant in which I was employed. One was clearly involved in a formal organisation which had one ‘sociology’; one was a member of an occupation which had another quite distinct ‘sociology’; one was dealing with industrial relations issues which were covered by yet another section of the literature . . . and so on. And a large proportion of the material contained in these subsections seemed to be dealing with issues far removed from the concerns of the classical writers in the sociological tradition, writers whom I felt had raised issues about the place of work in society which were still of crucial importance.

Rose has commented that ‘special sociologies are largely artificial creations, which result partly from careerism among academics, partly from tidy-mindedness amongst teaching administrators and partly from a sloppy kind of commonsense thinking’ (Rose, 1975, p. 14). But the concern here is not with reintegrating these special sociologies simply for the sake of integration, or to create an even tidier structure. Both the splitting-off of the sociological study of work from the main stream of sociology as well as the subsequent subdividing of this study are seen as highly unfortunate. In as far as work is central to the lives of a large proportion of members of society, the study of work should retain a position at the centre of the study of society. And, since people tend in their experience of work to become involved in organisational, occupational, professional, industrial relations and motivational issues, it seems reasonable to look at these issues sociologically with the expectation of there being interconnections between them. It might be argued in response to this that sociologists, like any other academics, must specialise in order to come to terms with the vastness of reality. But this does not justify the developing of separate analytical frameworks for these areas which, by their very nature, tend to preclude the seeking of interconnections between different elements of people’s work behaviour and experience. Where As one recognises and sees value in a multiplicity of perspectives within the general discipline of sociology, one is bound to question a situation where this diversity not only leads to the dividing of what might be indivisible in experienti...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1. The sociological framework

- 2. Industrialisation, rationalisation and the emergence of the personnel occupation

- 3. Personnel management: conflicts and ambiguities

- 4. Occupational entry

- 5. Orientations, values and adjustments

- 6. Professionalism: symbol and strategy

- 7. Ideas, knowledge and ideology

- 8. Organisational power and influence

- 9. Social integration, personnel management and social change

- Appendix 1: The interview sample – composition

- Appendix 2: The interview

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index