eBook - ePub

Approaches to Substance Abuse and Addiction in Education Communities

A Guide to Practices that Support Recovery in Adolescents and Young Adults

This is a test

- 300 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Approaches to Substance Abuse and Addiction in Education Communities

A Guide to Practices that Support Recovery in Adolescents and Young Adults

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book is designed to increase the awareness among mental health professionals and educators about the potential sources of support for students struggling with substance abuse, addiction and compulsive behaviors. The book includes a description of the scope of the problem of substance abuse in high schools and colleges, followed by sections describing recovery high schools and collegiate recovery communities. A further unique component of this book is the inclusion of material from the adolescents and young adults whose lives have been changed by these programs.

This book was published as a special issue in the Journal of Groups in Addiction and Recovery.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Approaches to Substance Abuse and Addiction in Education Communities by Jeffrey Roth,Andrew Finch in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Didattica & Consulenza nella didattica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Rationale for Including Recovery as Part of the Educational Agenda

In recent years, adolescent and young adult alcohol and drug use has garnered attention from scholars, legislators, parents, and the media. There is disagreement as to whether substance abuse by this population is in decline or as problematic as ever. The side one takes depends upon which data is used and how that data are interpreted. While the extent of the issue for adolescents and young adults is in dispute, the existence of problem drug use among this group is not. In 2005, 2.1 million youths in the United States aged 12 to 17 (8.3% of this population) met the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) diagnostic criteria for a substance use disorder—that is, dependence on or abuse of alcohol or illicit drugs (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2006). More than 918,000 U.S. college students can be diagnosed as alcohol dependent, and on an average campus of 30,000 students, nearly 9,500 meet the criteria for substance use disorders (Harris, 2006).

For good reason, there has been extensive literature devoted to preventing young people from developing an alcohol or drug problem, early identification and assessment of those who are developing a problem, and evidenced-based interventions and treatment for those who are exhibiting problem use or dependence. The case can be made that investment in prevention and early identification programs can benefit everybody who listens to the message. Some may choose never to drink alcohol or use drugs, others will learn to do so responsibly, and for those who do not use substances responsibly, either harm can be reduced or treatment administered.

Far less attention has been paid, however, to those students who have finished treatment. Studies on posttreatment continuing care are growing, but they still are outnumbered by prevention and treatment studies. Programs for students in recovery exist primarily as “aftercare” programs in treatment centers, and these vary in client commitment. Indeed, with less than only about 1% of adolescents and young adults receiving treatment annually (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2006), it can be difficult to channel funds toward programs that support their recovery.

The data that has been collected on adolescents and young adults after receiving treatment portrays a grim picture. Treatment outcome studies have found first use posttreatment to be 42% in the first 30 days (Spear & Skala, 1995, Table 6), 64% by 3 months (Brown, Vik, & Creamer, 1989), 70% by 6 months (Brown, Vik, & Creamer, 1989), and 77% within one year (Winters, Stinchfield, Opland, Weller, & Latimer, 2000). By 12 months, 47% return to regular use (Winters, Stinchfield, Opland, Weller, & Latimer, 2000). While some of this can be attributed to the quality of the treatment program, much can be attributed to the environmental factors in place after treatment (Godley, Godley, Dennis, Funk, & Passetti, 2002). Adolescents and young adults develop their identities through peer connection and interaction. Once young people have decided to stop using alcohol or drugs, the people with whom they interact and the support systems available will play a major role in determining their success.

This volume is about those systems of support—specifically, systems of support within educational communities. Obviously schools provide a major, if not the main, system of peer interaction and support for adolescents and young adults. According to the U.S. Department of Education, 57% of the U.S. population aged 3–34 is enrolled in a school, and this does not include trade schools or correspondence programs. At age 14 and 15 (the standard age for starting high school), 98.5% of the population is in school. By age 22 through 24 (when many are finishing college), 25% of the population is still in school (Figure 1).

This means that when a person decides to seek help for a substance use disorder, anywhere from a fourth to nearly all of those people—depending on their age—will be involved with an educational community. And young people between ages 14 and 18 will most likely be in a school community every day, seven hours per day. The education community for boarding

FIGURE 1. Percentage of the Population 10 to 24 Years Old Enrolled in School, 2004

NOTE: Includes enrollment in any type of graded public, parochial, or other private schools. Includes elementary schools, middle schools, high schools, colleges, universities, and professional s chools. Attendance may be on either a full-time or part-time basis and during the day or night. Enrollments in “special” schools, such as trade schools, business colleges, or correspondence schools, are not included. (U.S. Department of Education, 2006, Table 6).

school students and many college students often represents the entire living and social community as well.

Regardless of age or living arrangement, though, education communities provide a powerful source of influence upon adolescents and young adults, and thus there exists both opportunity and risk. The risks have been well documented through substance use and abuse studies and efforts to prevent problem use or reduce the harm of substance “misuse.” Efforts to create “social norms” around “responsible” drinking and drug use in order to eliminate “binge” drinking on high school and college campuses have taken root in education communities over the last decade. Though the effectiveness of prevention programs like DARE. (Hallfors & Godette, 2002) and social norms theory (Polonec, Major, & Atwood, 2006) has been disputed, the good news is that the recent reports suggest adolescent substance use and abuse may be in decline (Johnston, O'Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2007; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2006). The intense focus on the “teen drug problem” appears to be working.

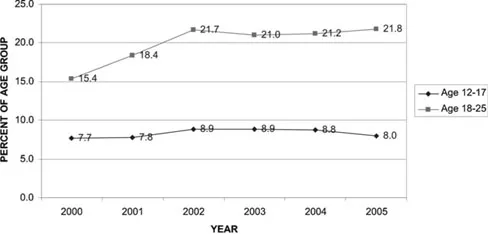

The number of students ages 12–17 needing and receiving treatment for alcohol or drug use problems or dependence, however, has stayed

FIGURE 2. Substance Abuse or Dependence, by Age

NOTE: Criteria for dependence on or abuse of a substance is based on usage in the past 12 months. Substances include alcohol and illicit drugs, such as marijuana, cocaine, heroin, hallucinogens, and inhalants, and the nonmedical use of prescription-type psychotherapeutic drugs. Classifications are based on criteria specified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). According to the NSDUH, dependence is considered to be a more severe substance use problem than abuse because it involves the psychological and physiological effects of tolerance and withdrawal. Although individuals may meet the criteria specified for both dependence and abuse, persons meeting the criteria for both are classified as having dependence, but not abuse. Persons defined with abuse do not meet the criteria for dependence (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2006).

consistent. In 2000, SAMSHA's National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH)—formerly the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse—began reporting the number of people with a substance use disorder by age group. From 2000–2005, the percentage of people with a substance use disorder rose from 15.4% to 21.8% for ages 18–25 and hovered between 7.7% and 8.9% for ages 12–17 (see Figure 2) (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2006).

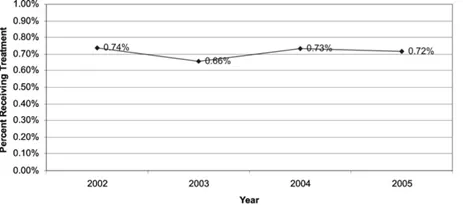

Since 2002, when the NSDUH began reporting the percentage of people needing and receiving treatment for a substance use disorder in a “specialty treatment center,” just under 9% of the population aged 12–17 has needed treatment (see Figure 3), and just under 1% has gotten it (see Figure 4) (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2006). Policymakers often focus on the obvious “treatment gap,” which is the difference between those needing and those receiving treatment—a mean of 8% over the four years. Factors such as treatment availability, cost of treatment, and client demographics and culture impact the size of the “gap.”

FIGURE 3. Needing Specialty Treatment for Alcohol or Illicit Drug Abuse or Dependence, Ages 12–17

Recovery support programs are concerned with the size of the treatment gap. If people who need treatment—whether it is brief or long-term— cannot get it, they will have no recovery to support. Student assistance programs have existed since the 1970s to identify and assist students at risk

FIGURE 4. Receiving Specialty Treatment for Alcohol or Illicit Drug Abuse or Dependence, Ages 12–17

NOTE: SAMHSA defines specialty treatment as treatment received at any of the following types of facilities: hospitals (inpatient only), drug or alcohol rehabilitation facilities (inpatient or outpatient), or mental health centers. It does not include treatment at an emergency room, private doctor's office, self-help group, prison or jail, or hospital as an outpatient. An individual is defined as needing treatment for an alcohol or drug use problem if he or she met the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) diagnostic criteria for dependence on or abuse of alcohol or illicit drugs in the past 12 months or if he or she received specialty treatment for alcohol use or illicit drug use in the past 12 months (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2006)

for substance use problems, and these programs have provided a gateway to treatment as well as aftercare for students. Parents may be oblivious to or contributing to the problem, and parents simply do not see their teenage children for the blocks of time around peers that schools do on a daily basis. Once these young adults go to college, parental contact and involvement usually becomes sporadic and episodic. Thus, school-based identification, intervention, and treatment efforts may be the best chance for some students to access services.

Beyond the treatment gap, however, recovery support programs are keenly aware of the data in Figure 4. Though the percentage of high school students receiving treatment at a specialty treatment center has remained under 1% of that population, the raw number of students age 12–17 reveals a range of 168,000 to 186,000 high school students receiving treatment annually from 2002–2005. And as the treatment gap diminishes, the demand for appropriate and sound posttreatment programs could rise dramatically. While not every young person who uses (or abuses) substances requires treatment, hundreds of thousands do. The school environment they return to after that treatment experience will contribute to integration of the “gains” of treatment—or to the reemergence and/or worsening of pretreatment substance use.

EXISTING RECOVERY SUPPORT LITERATURE

This volume will provide the deepest review yet of the existing literature on the continuum of care for adolescent and young adult substance use disorders. Post-treatment continuing care services have long been seen as an “essential” component of the treatment continuum (Brown & Ashery, 1979; Hawkins & Catalano, 1985; McKay, 2001). With some exceptions, however (Godley, Godley, Dennis, Funk, & Passetti, 2002; Spear & Skala, 1995; Winters, Stinchfield, Opland, Weller, & Latimer, 2000), overall research about posttreatment continuing care for adolescents and young adults has been limited. Even thinner is research conducted on recovery schools, which has been limited to theses and dissertations (Doyle, 1999; Finch, 2003; Rubin, 2002; Teas, 1998), single-site evaluations (Diehl, 2002), and unpublished reports (Moberg, 1999; Moberg & Thaler, 1995).

Professional publications have begun to embrace the concept to frecovery support in schools as an emerging field. Recovery historian William White recently coauthored a history of recovery schools and has also looked closely at collegiate recovery communities in particular (White, 2001; White & Finch, 2006).Other professional pieces have examined first person perspectives and challenges facing the expansion of recovery schools (e.g., Finch, 2004). Hazelden has also published a startup manual for recovery high schools (Finch, 2005).

One area where school recovery support programs have received more broad support is the popular media. Television, newspapers, and Internet sites have featured many “human interest” stories from high schools and colleges since the early 1990s. While these stories may lack the rigor of a refereed journal, they have also shined a light on programs and provided a forum for testimonials. This has allowed recovery programs in high schools and colleges to garner support, and 25 recovery high schools and six collegiate recovery communities opened across the United States from 1999 to 2005 (White & Finch, 2006).

McKay (2001) outlined a series of future directions in research on continuing care, and, by design, this volume addresses one of McKay's key concerns: characterizing types of continuing care services and documenting how widely available they are. McKay also called for identifying the types of continuing care services that are associated with the best outcomes, and many of the articles here addre...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- 1. Rationale for Including Recovery as Part of the Educational Agenda

- 2. Authentic Voices: Stories from Recovery School Students

- 3. Twelve Step Meeting—Step One

- 4. Schools as a Collection of Groups and Communities

- 5. Adolescent Substance-use Treatment: Service Delivery, Research on Effectiveness, and Emerging Treatment Alternatives

- 6. Recovery Support Meetings for Youths: Considerations When Referring Young People to 12-Step and Alternative Groups

- 7. Twelve Step Meeting—Step Two

- 8. Recovery High Schools: A Descriptive Study of School Programs and Students

- 9. Restorative Justice

- 10. A Secondary School Cooperative: Recovery at Solace Academy, Chaska, Minnesota

- 11. The Insight Program: A Dream Realized

- 12. Achieving Systems-Based Sustained Recovery: A Comprehensive Model for Collegiate Recovery Communities

- 13. The Need for a Continuum of Care: The Rutgers Comprehensive Model

- 14. An Exploratory Assessment of a College Substance Abuse Recovery Program: Augsburg College's StepUP Program

- 15. Reflections on Chemical Dependency in a College Setting and Its Intersection with Secondary School Programs

- 16. Twelve Step Meeting—Step Twelve

- Index