eBook - ePub

Neuropsychology of Art

Neurological, Cognitive and Evolutionary Perspectives

This is a test

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The book provides extensive up-to-date neuropsychological and neuroscientific background for understanding the brain's modulation of art production, in both the visual and musical arts

It is the first time that evolutionary, biological, and neuropsychological issues and evidence are brought to bear in a single book to explain the relationship between multiple components of the arts and the brain

It is also the first time that there is extensive description of consequences of brain damage in many established artists and what this implies to the brain's control of art.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Neuropsychology of Art by Dahlia W. Zaidel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1Approaches to the Neuropsychology of Art

Introduction

Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, with the establishment of a correlation between language functions and brain regions within the left cerebral hemisphere, there has been a trend in neuropsychology to link specific cognitions with discrete regions of the brain. This has largely been accomplished through studies of fractionated behavior following acquired brain injury in neurological patients. The location of the damage, together with the consequent behavioral breakdown, opened windows on mind-brain associations involving language, perception, memory, motor skills, personality, and what are generally considered to be higher cognitive functions. The components of behavior have to be defined in order to make such associations. The association between art and brain, however, has proven difficult because its components are elusive. What abilities of Michelangelo’s mind went into painting the Sistine Chapel or sculpting Moses or the Pietà? What in Monet’s mind controlled his water lily paintings, or in Gauguin’s his Ancestors of Tehamana painting, or, in ancient artists, the cave walls at Lascaux and Altamira? Similarly, what were the components of Verdi’s mind when he composed Aida? And what brain mechanisms were at work in the great plays, poems, literature, and ballets that continually remain sources of attraction and fascination? The answers to some of these challenging questions can be explored with the perspectives of neuropsychology.

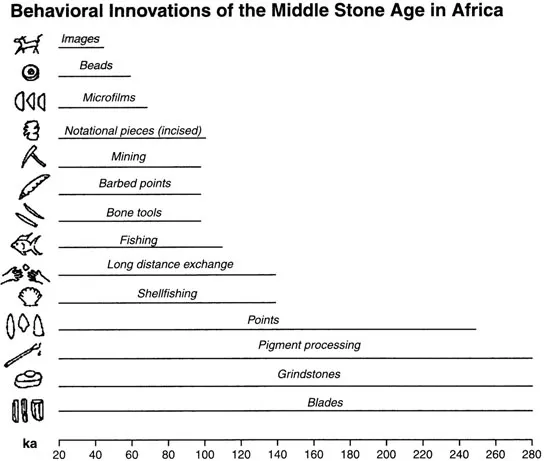

While practically everyone in society, at an early age, can learn to speak and comprehend language, only a select few in modern Western society can create art with qualities that elicit pleasure and appreciation for centuries and even millennia. Because the compositions of such artists seem to incorporate special and unique abilities, their biological basis in the brain remains a challenge. Neuropsychological methods can provide only a partial view into the “neuro-map” of art. To gain further clues and insights we need to consider the life of early humans, evolution of the human brain itself as well as evidence and discussion from diverse fields such as archaeology, biology, mate selection strategies, anthropology, the fossil record, and ancient art. Abundant human art is said to have emerged between 35,000 and 45,000 years ago in Western Europe (Bahn, 1998). The changes in the morphology of the human brain coupled with archaeological evidence of art-related relics along with the biological development of various cognitive abilities suggest that surviving ancient etchings, paintings, statues and figurines, particularly from this Western European Paleolithic period, were not sudden expressions of mind and brain. Instead, the evidence suggests that the underlying neuroanatomy and neurophysiology evolved slowly, well before that period and may have supported earlier artistic expression (McBrearty & Brooks, 2000). Figure 1.1 illustrates cave art from Western Europe dating to 30,000 years ago (Valladas et al., 2001) and Figure 1.2 illustrates much earlier beginnings of human art in Africa (McBrearty & Brooks, 2000).

Figure 1.1Prehistoric cave art from Western Europe (Valladas et al., 2001). This was drawn about 30,000 years ago in the Chauvet cave in Vallon-Pont-d’Arc, Ardèche, France, as determined through radiocarbon dating. On the upper left corner we can see several horses, and in the center at least one rhinoceros. It belongs to the Aurignacian period in Western Europe. This predates the better known cave art from Altamira and Lascaux, which are thought to have been painted some 12,000 to 17,000 years ago. They belong to the Magdalenian period. (Printed with permission from Nature Publishing.)

Figure 1.2This is a summary of the emergence of art forms in Africa (McBrearty & Brooks, 2000). (Reprinted with permission from Journal of Human Evolution.)

Neurological disorders have been described predominantly in visual and musical artists. Very little is known about the neural substrates of art (the neuro-components) in creative writing both because there is a dearth of known writers with localized cortical damage and because language is often so seriously disrupted following left hemisphere damage (no published cases of writers with right hemisphere damage are known to me) that insights into writing processes are effectively denied (Alajouanine, 1948). Consequently, the emphasis here is on individuals engaged in the visual and musical arts.

The relationship between art and the brain needs to be charted. The relationship can benefit a great deal from exploring deficits in established artists after they have sustained brain damage. Searching and documenting patterns in their artistic endeavors following the damage helps reveal aspects of the relationship, zero in on the anatomical and functional underpinning, and identify questions brought up by the patterns.

Definitions and Purpose of Art

What is art? Art includes paintings, sculptures, pottery, jewelry, drawings, music, dance, theater, creative writing, architecture, film (cinema, movies), photography, and many additional fields. These are but examples. The list is long. By and large there seems to be a consensus that art is a human-made creation with a social anchor that communicates ideas, concepts, meanings, and emotions, that art represents talent, skill and creativity, that it gives rise to pleasure through the elicitation of an aesthetic response, even while, for the most part, art does not seem to have a direct utilitarian purpose. At the same time, a myriad of examples of art works throughout the world complicates the imposition of clear-cut, precise, or logical boundaries on art as a category of human creation.

The wide range of possible human activities that express art is described by anthropologist Ellen Dissanayake (1988):

Perhaps the most outstanding feature of art in primitive societies is that it is inseparable from daily life, also appearing prominently and inevitably in ceremonial observances. Its variety is as great as the kinds of lives (hunting, herding, fishing, farming) and the types of ritual practices (ceremonies to ensure success in a group venture or to encourage reunification after a group dissension; rites of passage; accompaniments to seasonal changes; memorial occasions; individual and group displays). All these may be accompanied by singing, dancing, drumming, improvisatory versification, reciting, impersonation, performance on diverse musical instruments, or invocations with a special vocabulary. Decorated objects may include masks, rattles, dance staves, ceremonial spears and poles, totem poles, costumes, ceremonial vessels, symbols of chiefly power, human skulls; and objects of use such as head rests or stools, paddles, dilly bags, pipes and spear-throwers, calabashes, baskets, fabric and garments, mats, pottery, toys, canoes, weapons, shields; transport lorry interiors and exteriors; cattle; manioc cakes and yams; or house walls, doors, and window frames. Songs may be used to settle legal disputes or to extol warriors as well as for lullabies and the expression of high spirits. A large part of the environment may be rearranged and shaped for initiation or funeral rites; theatrical displays may go on for hours or days. There may be painting on a variety of surfaces (ground, rock, wood, cloth); piling up of stones or pieces of roasted and decorated pork; considered display of garden produce; body ornamentation (tattooing, oiling, painting). Many of these occasions for art have counterparts in the modern developing world.

(Dissanayake, 1988, pp. 44–15)

As this description shows, art can be many things. We in Westernized societies typically think of art as something viewed in museums or seen in the theater or heard in a concert hall or read in a book. By comparison, the list of artistic expressions provided by Dissanayake demonstrates the motivation, need, and drive as well as the capability that humans possess to create boundless expressions of art. Language, the prime example of the human mind, is characterized by its combinatorial power and infinite potential to create units of meanings through vocabulary and syntax. In this regard, art and language share the same cognitive underpinning. Art can be infinitely combinatorial too. It should thus not be surprising that the art of many human societies is nearly limitless in creativity and skill.

Multiple Components of Art and Brain Damage in Established Artists

How are we to understand the neuroanatomical and neurophysiological underpinnings of all of these artistic expressions? A unified behavioral expression represents a complex conglomerate that is more than the sum of its parts, with several brain regions simultaneously involved in its execution. Art production is not alone in this regard. Mere observations of psychological phenomena or theorizing alone are not sufficient to uncover the components of complex behaviors, abilities, and talents. At the same time, the ability to create art is just as susceptible to breakdown and fractionation following brain damage as other behaviors are, which suggests that some of its units and mechanisms can be unmasked. Similarly, sensory deficits in artists, particularly with vision and hearing, can throw additional light on the final artistic product. A painting by Vincent van Gogh, for example, is a unified product, the execution of which required multiple components from diverse functional domains including visual perception, color vision, creativity, fine finger dexterity, motor control, eye–hand coordination, conceptual understanding, spatial perception, problem solving, reasoning, memory – to name but a few requirements. And, of course, it is the fusion of the elusive attribute of talent with training and expertise – the unique decision-making apparatus determining the nature of the composition, the colors, the lines, tilts, angles, and so on – that needs to be understood against the background of neuroanatomical substrates. Currently, rather than a single region, given the available data, it would appear that art is the functional realization of multiple components that engage many regions in the brain.

The perspective adopted here is that the most useful insights into the neuroanatomical underpinnings of the complex process of creating art can be gleaned from the consequences of brain damage in established professional artists, those whose works have been exhibited, appreciated, studied, sold, discussed, remembered, and admired prior to the injury. It is clear that they have artistic talent, creativity, and skills. The more localized the damage is to a specific region, the more valuable it is for reaching conclusions regarding these underpinnings. The main neuropsychological interest lies in emergence or not of alterations following the damage, and if alterations do occur, what are their causes. The cognitive underpinnings of art production and appreciation as revealed through brain damage in artists is little explored, largely because localized damage in such artists is rare. Even the cognitive underpinnings of art as studied under laboratory conditions in normal subjects with intact brains is quite complex and has yet to fully explain such important issues as talent, skill, and creativity.

It should be kept in mind that art conception and construction following the damage is the outcome of combined activity of both healthy and diseased tissue. Or viewed in another way, the work is reflection of the brain’s reaction to neural irregularity (Calabresi, Centonze, Pisani, Cupini, & Bernardi, 2003; Dufiau et al., 2003; Kapur, 1996; Ovsiew, 1997; Rossini, 2001). Functional reshaping of the brain consequent to damage is currently under increasing scrutiny with neuroimaging techniques, particularly with respect to language (Duffau et al., 2003). Functional reorganization is an issue that should be considered in contemplating the neural support for art (and this is discussed in the last section of Chapter 4).

Artists with sensory problems in vision or hearing highlight a main argument of this book, that art is a complex expression of experience, conceptual and memory systems, talent, skill, and creativity. Artists with seriously compromised vision due to disease, for example, are able to continue painting (see Chapter 3), while musicians with extremely poor hearing go on composing (see Chapter 5). A blind artist, Lisa Fittipaldi, untrained in art before the onset of her blindness, was nevertheless able to paint competently in color. Artists with progressive debilitating effects of Parkinsonian tremors were able to hold and control the paintbrush. The latter artists and their various conditions are discussed in Chapter 2.

Visual Arts, Perception, and Neuropsychology

Neurological patients with damage to either the left or the right hemispheres are often required in the clinical or laboratory to interpret, manipulate, organize, arrange, match, or name pictures. Indeed, using pictures in neuropsychological testing is a widespread practice. Inferred function from the outcome of these tests is useful to explorations of the neuroanatomical underpinnings of the visual arts. The pictures may depict realistic objects or simple geometrical shapes. Damage to either hemisphere does not necessarily result in apictoria (the inability to derive meaning from any type of pictorial material). Behavioral impairments may also be seen depending on the nature of the task. Similarly, damage to either hemisphere does not obliterate the ability to draw some basic, common visual percepts. The laterality of the damage may, however, affect the characteristics of the drawings as well as the depiction of depth.

Production of art works recruits activity of several brain regions and their functions. The list includes planning, motor control, hand-eye coordination, the hippocampal formation, memory, long-term memory, concepts, semantic knowledge of the world, emotional circuitry, the parietal lobes, the control of meaning and space, global and detailed perception, disembedding strategies, sustained attention, and other widespread neuronal networks. Put another way, the arts exemplify neuropsychology in action. Realistic depictions of, for example, nature scenes, still lifes, animals, human figures and faces, all require spatial cognition; such figures can also be depicted in abstract forms. Both the right hemisphere and the detailed, analytic, and sustained attention of the left hemisphere are simultaneously involved in the production of visual art. In the visual arts, the tilt, angle, size, shape, form, height, or depth of the elements in relation to each other constitute the theme of a picture. In a rare case of an artist drawing a portrait while his eye and hand movements were being monitored by a specialized tracking device, it was found that, rather than starting with a global contour of the visual model – something associated with the right hemisphere and its cognitive style – the artist, Humphrey Ocean, nearly always began with a detail first, working his way from the inside outwards (Miall & Tchalenko, 2001). The attention to local details is precisely the cognitive style associated with the left hemisphere. A similar observation was made regarding the drawing approach of Nadia and EC, two autistic savant artists with exceptional graphic abilities for depicting realistic figures (see Chapter 4); they started with the details within the containing form and proceeded from there to complete the contour frame (Mottron & Belleville, 1995; Mottron, Limoges, & Jelenic, 2003). This strategy demonstrates that both hemispheres concurrently play significant roles in the production of visual art.

Sometimes, to achieve a particular effect, artists, in their depictions, violate the rules of natural physical space. It is the left hemisphere that specializes in processing incongruous combinations of reality (Zaidel, 1988a; Zaidel & Kasher, 1989). The best known genre where realistic objects, or their parts, are juxtaposed incongruously so as to violate physical rules of reality is that of the artist René Magritte, and other artists in the school of Surrealism; prior to that school, artists such as Manet and Cézanne experimented with established notions of spatial relationships. Figure 1.3 provides examples of Magritte’s work. In Asian and ancient Egyptian art we find abundant examples of an absence of three-dimensional representat...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Series preface

- Preface

- 1. Approaches to the neuropsychology of art

- 2. The effects of brain damage in established visual artists

- 3. The eye and brain in artist and viewer: alterations in vision and color perception

- 4. Special visual artists: the effects of autism and slow brain atrophy on art production

- 5. Musical art and brain damage I: established composers

- 6. Musical art and brain damage II: performing and listening to music

- 7. Artists and viewers: components of perception and cognition in visual art

- 8. Neuropsychological considerations of drawing and seeing pictures

- 9. Beauty, pleasure, and emotions: reactions to art works

- 10. Human brain evolution, biology, and the early emergence of art

- 11. Further considerations in the neuropsychology of art

- 12. Conclusion and the future of the neuropsychology of art

- Glossary

- References

- Author index

- Subject index