![]()

Europe and the Industrial Revolution in Britain

The Agricultural Base of Society

The Nobility

Systems of Land Management

- In France

- In Germany

- In Spain

- In the Netherlands

- In Scandinavia

- In the Habsburg Empire

- In Poland and Russia

- In Romania

- Conclusion

Farming Methods and Agricultural Improvement

Obstacles to Improvement

The Industrial Sector

- Artisanal Industries

- Iron Manufacture

- Coal Mining

- Domestic Industries

Trade and Markets

Obstacles to Trade

Conclusion

Suggested Reading

EUROPE AND THE INDUSTRIAL

REVOLUTION IN GREAT BRITAIN

An increase in the volume of production in the British Isles, sustained with few interruptions throughout the eighteenth century, increased much more rapidly in the last few decades of that century. Changes in the organisation and techniques of production, which had already been developing for a long time, burst into greater prominence in an efflorescence of technological invention, and the widespread social and economic changes which came as a consequence produced the expression ‘Industrial Revolution’.

The description of these events as a ‘revolution’ is justified on every ground because the technological changes, especially the discovery of new techniques of manufacture in the metal and textile

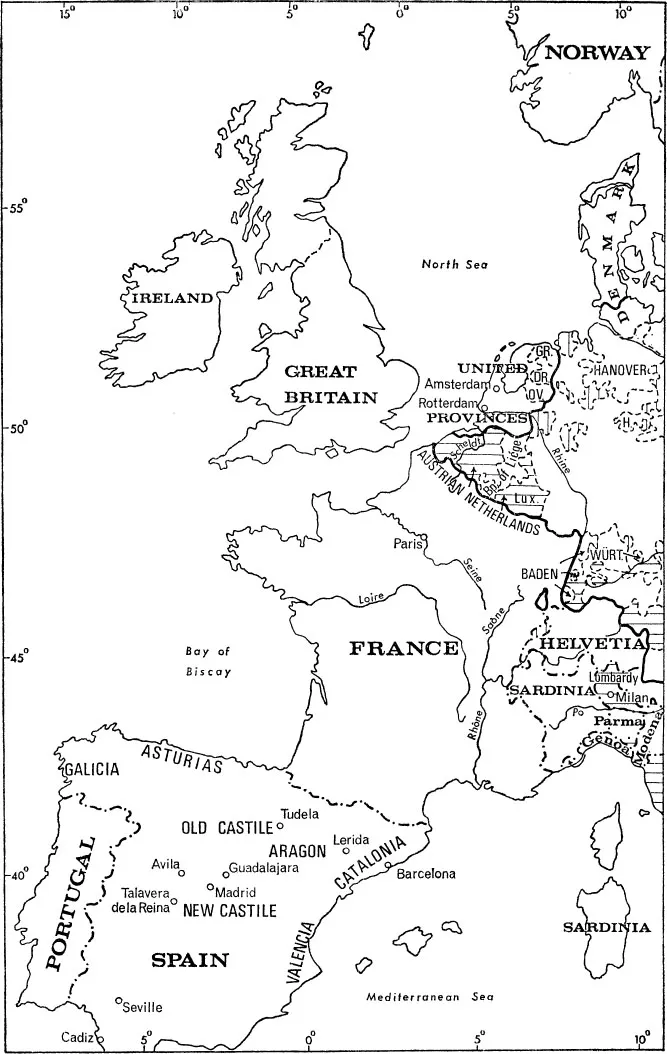

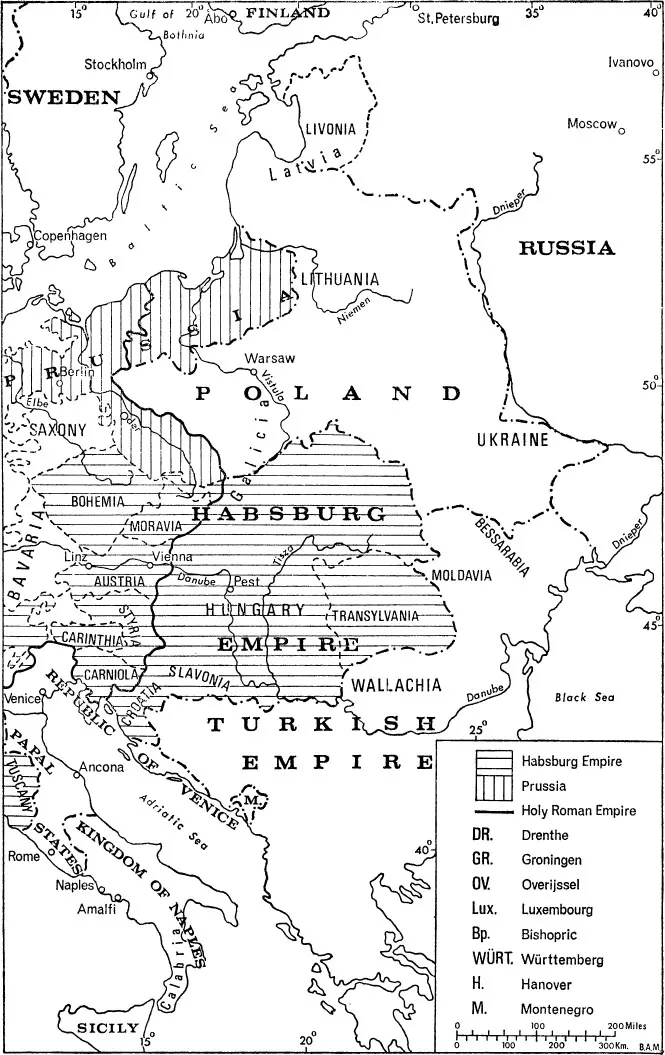

Map 1. Europe in 1780

industries, changed the whole structure of social organisation and the patterns of life and thought of eighteenth-century Britain. A new society emerged whose social structure was determined by the mechanics of industrial production rather than by those of agriculture. If our attention is confined merely to the technological changes themselves, the concept of an industrial ‘revolution’ in the 1780s becomes only a British phenomenon. The astonishing occur-rence of a number of inventions in a short space of time and the rapid concentration of capital and labour in factories, which occurred partly as one consequence of these inventions, give even the merely technological aspects of these changes a revolutionary aspect in Britain because of the speed with which they took place. These innovations were adopted more slowly in most parts of the continent of Europe so that the concept of an industrial ‘revolution’ at the end of the eighteenth century in this narrower sense has no great relevance outside the field of British history. But all the first and greatest analysts of these events, Smith, Ricardo, Saint-Simon, Engels and Marx, set out to analyse, not a series of changes in industrial techniques as such, but the quite new economic basis which these changes created for human society. In this wider sense the industrial revolution was a European phenomenon from the outset. From the continent, what had taken place in late eighteenth-century Britain was seen, and correctly seen, as profoundly revolutionary, threatening the very foundations of social organisation. The developments in manufacturing industry transformed the economic position of Britain in relation to the European lands and by changing the balance of economic power, changed also the balance of political power. At the same time these events in Britain posed profound social questions to European society. To some, they were a fearful menace to a much-valued social position and way of life, to others a way of improving their income and to many a wonderful new hope for the overturning of a society they detested.

It is only in the light of these fears and hopes of social revolution that the Industrial Revolution in continental Europe can fully be understood. The enormous increase in productive capacity in Britain demanded, if only for reasons of political power, a similar response on the continent. From the very start therefore, the economic developments in Britain seemed certain to spread to mainland Europe and their coming was anticipated with different feelings by different parties. British society was transformed by internal forces, but the first industrial revolution could only happen once. Continental societies were transformed by events coming from outside, captured by forces which their leading groups could often not help but regard as enemy forces.

‘The Industrial Revolution’ should not be confounded either with ‘industrialisation’ or with ‘economic growth’. Both of these last were possible in the eighteenth-century European society without revolutionary implications. They were in fact typical of the more developed nations. Both could and did take place in perfect harmony with the social arrangements and political structures of many European states, whereas the industrial revolution, an altogether larger phenomenon, implied nothing less than the destruction of the old social and political order. The growth of industrial output and an increase in the number of people employed in manufacturing industry, which together might be defined as ‘industrialisation’ and, also, in so far as it can be measured for that period, the stricter conception of ‘economic growth’ had both been marked features of eighteenth-century Europe.

The output of the French cotton cloth manufacturing industry, or at least its consumption of raw cotton, seems to have grown at an annual average rate of 3.8 per cent before 1788, and so did the output of the coal mining sector. Although the data for constructing such a series for agricultural output are especially unreliable, present work suggests that there was a growth of 60 per cent in final agricultural output in France between 1701–1710 and between 1781–1790. Perhaps such an estimate is too high, although it should be borne in mind that the more fragmentary evidence about the growth of agricultural output in Germany over the same period also indicates a striking increase in production. The population figures for the early eighteenth century are not precise either but on the whole it does not seem unreasonable to accept that the overall rate of growth of the French economy in the eighteenth century was about, or slightly above, 1 per cent per annum. It was, therefore, growing at about the same rate as, or perhaps slightly faster than, the British economy.

It is not yet possible to impute rates of growth to other European economies in that period. However, it was a period of economic recovery from the disastrous famines and murderous wars of the previous century, and in almost all economies a noticeable increase in agricultural output and a noticeable increase in the output of some industries is to be remarked. The expansion of the agricultural frontier in Germany, particularly in Prussia, into lands often deserted as a result of war in the first part of the seventeenth century, and in Russia into lands never previously ploughed, led to an increase in the amount of bread grains (rye and wheat) produced. Towards the end of the century, the volume of these grains traded internationally seems to have increased although the totals remained very small. Stettin (Szczecin) and Odessa developed as ports for grain export. Similarly, Naples developed as a port for the export of olive oil from Calabria, where the olive trees began their relentless march over the countryside as peasant farmers began to produce for northern European markets and for Marseilles soap works. Examples from industry are not hard to find; the output of pig iron in Russia increased from 110,000 tons in 1718 to over 163,000 tons in 1800, while there was at the same time an increase in the output of handicraft goods. In Valencia and Catalonia, the development of the cotton and silk manufacturing industries after 1750 awoke Spain from its long industrial stagnation and made it once again, in mid-eighteenth-century terms, into an industrial power while establishing the modern economic supremacy of Catalonia over Castile. These are but a few of the many examples which might lead us to suspect that measurable economic growth was also taking place elsewhere in Europe, although only in certain restricted regions. That growth was reflected in the great increase of international trade, both between European countries and between Europe and its many colonies. The last half of the eighteenth century witnessed a remarkable increase in the diversity of goods traded and in the number of economies participating in these trades.

The study of economic history in Britain has always focussed attention on the problem of why the industrial revolution occurred there. Obviously it is not part of this book to try to answer that question. But clearly such a question also has implications for continental society since its answer, by identifying important economic differences between Britain and the continental economies, might suggest much about the economic history of mainland Europe. It is, however, only one method, and not an especially important one, of approaching the economic history of the mainland. It is unfortunately, an approach which has dominated most British economic history writing about other European societies, a fact which has meant that their economic history has been constantly measured against a British yardstick: Britain has been seen as the norm for economic development in this period and all other societies as aberrations. Most theoretical models of growth or development were derived until very recently at no very great distance from the objective historical experience of the industrial revolution in Britain. It is possible that such an approach, leaving aside the distorted view of the history of the mainland which it necessarily presents, is also misleading about internal developments in Britain for it tends to exaggerate the differences between eighteenth-century Britain and many other European societies. Neither socially nor economically was eighteenth-century Britain strikingly different from all other European countries. And it was for that reason that the industrial revolution there immediately aroused so much interest elsewhere in Europe.

It has often been suggested that the industrial revolution in Britain was the consequence of a process of continued industrialisation in the eighteenth century, that it was an acceleration of industrialisation to such a speed that it became a qualitatively different process. But most recent research into the French economy in the eighteenth century has demonstrated that the increase in industrial output per head in the eighteenth century was probably faster than that in Britain. It has become, as a consequence, much less easy to explain the occurrence in Britain, in the last quarter of the eighteenth century of the new phenomenon of industrial revolution. The spread of industrial handicrafts, particularly the manufacture of cloth, and the development of the iron industry, to both of which scholars drew attention as the origins of the industrial revolution in Britain, were equally marked in eighteenth-century France. Nor were they lacking in many other European economies. If this general explanation no longer seems valid, this is more true of the more detailed and specific explanations frequently offered. Usually these take the form of isolating one particular factor in the British economy in the eighteenth century lacking in other European economies or, to put it another way, of finding the precise advantage of the British economy over the least disadvantaged of all the mainland economies.

For example, a factor frequently so isolated is the price of coal. The technological changes in the British industrial revolution depended on a ready supply of cheap coal. Mass production in the textile industries was accompanied by the utilisation of a new and much more powerful source of energy, James Watt's improved steam engine. The changes in the technique of iron manufacture hinged on the process of smelting iron ore by the use of coke, a product of coal. That coal was more widely available in Britain and at a cheaper price than on the mainland, has caused most scholars to consider this as a particular British advantage. Certainly the greater price of coal on the mainland was a factor of considerable importance in explaining why new manufacturing techniques were adopted more slowly there. But it should be remembered that coal was a very costly material to transport and that its relative cheapness was a regional effect in Britain as well as on the continent. It was cheap at the pit-head and its price increased sharply with the distance it was transported. In some parts of Europe it either was or could have been as cheap, and in those parts of continental Europe where it was not mined there were always possibilities of substitution except in the process of refining pig iron. In France, for example, the mass-production of textiles was based in many areas on the development of new methods of using water power.

Another specific advantage of the British economy is often said to have been the ready access to water transport. In an age when carriage by land was very expensive and slow, access to rivers or the sea drastically reduced the costs of carriage of raw materials. Obviously, many areas of France, Germany, or Spain were much further from navigable water than it was possible to be in Britain. Similarly, the development of a crude system of handling money and providing credit in eighteenth-century Britain has been noted and it has also been pointed out that in eighteenth-century France, for example, credit was difficult to obtain on any but the most swingeing terms. The great development of foreign trade in eighteenth-century Britain has also been used to explain the source of profit for investment and also the development of a market for manufactured goods and it has been justly pointed out that this development was much less marked in other eighteenth-century economies, in Germany and Russia for example.

The most frequent of such attempts to isolate a particular factor which may have caused the industrial revolution to take place in Britain has been the demonstration that British agriculture was differently organised from that of mainland Europe. The existence of a relatively restricted group of large landowners who let their land to tenant farmers many of whom were men of some wealth and standing and who in their turn employed a large force of paid labourers to cultivate the land was a phenomenon restricted almost entirely to Britain. Elsewhere in Europe the land was more usually cultivated either by the peasantry whose farms were small, but whose rights over the land could amount to something close to full ownership, or by a labour force whose labour was to some degree customary and compulsory and not so dependent on the wage contract as in Britain. It is usually supposed that the peasantry had ‘disappeared’ in eighteenth-century Britain because economic progress had proceeded further there and the organisation of agriculture which had ensued was a better base for future economic development than the more ‘archaic’ societies existing on the continent.

All these attempts to isolate single factors which can explain the fact that the first industrial revolution occurred where it did and also the attempts to build general models of economic development which incorporate a revolutionary experience akin to that in Britain tend to break down before the enormous diversity of the continental economies. The more their history in the eighteenth century is considered, the greater appears the difficulty of finding one single factor in the British economy not present in some continental economies. The possibility remains, of course, of explaining the occurrence of the industrial revolution in Britain as the result of a unique concentration of economic advantages not exactly possessed by any other economy. But this argument is too tautological to be of much value. It should also be remembered that interest in the first industrial revolution has been such that research has concentrated very heavily on it so that we know far more about the British economy in the eighteenth century than about other economies. And because this particular approach has dictated a particular path of research, we know far more about the disadvantages of continental economies compared to Britain than about their advantages. One example of this will suffice, that of the United Provinces. No country had such easy access to cheap water transport, its financial and commercial experience and techniques were more advanced than in Britain, the per capita value of its overseas trade was much greater, its social structure more flexible and its agriculture, although differently organised, as efficient and progressive as that of Britain, it was an exporter of capital. It had, however, no easily-minable reserves of coal. Is it possible to impute to this one lack the fact that the Netherlands did not undergo the experience of the industrial revolution when all the immediately surrounding areas did so? It should be remembered that even by 1914, when many countries with no worthwhile coal reserves had industrialised the Netherlands still remained a relatively unindustrialised land. The price of coal is too small a matter to be made the deciding factor in the occurrence and timing of nineteenth-century European industrialisation.

The more that is discovered about the history of economic development in Europe, the harder it becomes to define the precise economic differences between Britain and other eighteenth-century economies. Nevertheless, the impression remains, and quite justifiably, that in some way Britain was a more developed economy in the late eighteenth century. Consequently, economic historians have proposed another general explanation of the industrial revolution there, that it was the result of attaining a particular level of economic development. Britain, as it were, was ‘ripe’ for the industrial revolution; the continental economies were not. This ‘ripeness’ was constituted by a level of development in industry, agriculture and trade and a level of sophistication in economic and social arrangements which, although partly to be found in many continental economies, was nowhere wholly to be found to the same degree. Since the conjunction of economic factors which c...