![]()

1 Queer Women in Urban China

An Introduction

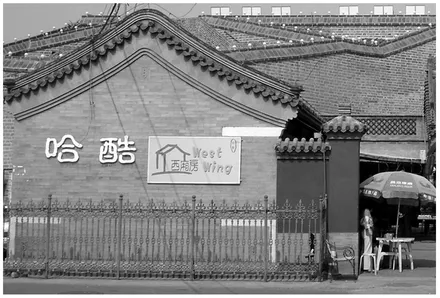

It is a warm late-summer Saturday night in August 2005, and the women-only Xixiangfang (West Wing) Bar in west-central Beijing is bustling with women, chatter, and heartfelt, if not entirely on key, karaoke singing. Due to the pleasant weather, the walled outside space of the bar, which constitutes the west wing or side house of a historic siheyuan (courtyard building), has been transformed into an outdoor karaoke bar. A big screen and projector are set up next to the entrance and are showing karaoke videos to the large audience seated at tables in the courtyard. Microphones are hooked up to the sound system, and the sound of popular Chinese pop songs, often melancholic ballads of lost love, is so loud that conversation is almost impossible. A deck has been placed under the roof by the main entrance, hosting a huge mix table expertly directed by Da Ge, a chain-smoking T (tomboy, masculine or butch lesbian). Meimei, Da Ge’s girlfriend, sits on a chair next to her, casually smoking cigarettes, taking karaoke requests, and assisting Da Ge whenever necessary. Flanking the turntable and DJ are two large loudspeakers blasting out tunes. Throughout the evening women line up to sing, the courtyard tables are packed, and even inside the bar many patrons are enjoying the party, drinking, smoking, talking, playing truth-or-dare card games, dancing, and flirting.

I chat with Shuchun, a T media professional in her early thirties, and ask her how it’s going with her ‘boyfriend’. Shuchun has a gay boyfriend whom she met on an online dating site for contract marriages. Like so many other tongzhi (comrade, meaning ‘gays and lesbians’) in China, they are planning a xinghun (marriage of convenience, also known as cooperative or contract marriage) to fit in, to please their parents and coworkers, and relieve the incessant pressure to marry. However, they have recently had several arguments about their very different views on life and their future, and now Shuchun is not so sure any more about the convenience of the planned marriage arrangement. Another woman seeks me out, someone I have not met before but who has heard about “the foreign lala (lesbian) researcher,” and wants to talk to me about the quanzi (circle, meaning ‘the lala community’). She is a T in her early thirties and says she is active in many of the Internet lala discussion groups. She confides that she finds the community

Figure 1.1 The West Wing Bar (photo by the author).

too luan (disorderly, casual), and she feels it is better to find stable love and likeminded friends in the ‘normal’ everyday world, although she concedes that there is a bigger risk of not finding a genuine lala in mainstream venues. After a short discussion of this topic, she tells me that she recently broke up with her girlfriend of several years. Her former girlfriend has now married a man and moved abroad with him. A friend of hers joins our conversation, and they discuss the difficulty for most lalas to be open with their families and society in general. There are two reasons why it is such a problem in China, they argue; one is the zhengju (political situation). Until only recently, homosexuality was considered a mental illness or abnormality, and discourse on sexual and gender diversity is severely censored. The other reason is the chuantong (traditional) foundation of Chinese society and view of women, including a strong focus on marriage and motherhood as women’s primary roles.

Throughout the evening I chat with a number of lalas I know from previous occasions and various lala groups, and I am also introduced to new people, some very young and others in their thirties. Wangmeng, from the weekly lala-gay badminton group Logoclub, waves me over to her table, wanting to introduce me to her new girlfriend, and to catch up in general. She complains about long work days that leave her too exhausted to join the weekly Saturday afternoon Lala Salon, or visit the West Wing Bar more often. Another friend, Jingmei, knows about my research project and comes over later in the evening to let me know about an upcoming contract marriage discussion meeting. “You should join and learn more about our marriage problems,” she tells me. A small group of foreign lesbians join the party, chatting happily alongside Chinese lalas and a few gay male friends who have been allowed entry by arriving with female friends.

Early the next morning I jump on a public bus and head out to the far west side of Beijing, to participate in a consultation meeting on gay jiankang (health) hosted by the Aizhixing Institute. Aizhixing has managed to attract domestic and international funding, produce and disseminate resources, and organize networking events on gay issues by expertly manipulating official censorship with vague descriptions of their work— for example, providing jiankang jiaoyu (health education) and addressing HIV/AIDS issues from a gongzhong jiankang (public health) perspective.1 Today’s event has about thirty participants, mostly gay men but also activists from Tongyu (Common Language), the Beijing-based lesbian, bi women and allies network established in early 2005, as well as young representatives from a gay and lala student group at Beijing University. I spot some older gay men and middle-aged lalas who were part of early social initiatives in the 1990s. It is a diverse gathering of activists, indeed.

The moderator begins by asking those who would like to record or take photos to identify ourselves and introduce our purpose and work, so that participants can then object or consent. I raise my hand and stand up to introduce myself and my research project. I tell them I am a PhD student in anthropology from a British university, and that I am there to learn more about gay and lala activities and yundong (movement) to assist my project on lala yawenhua (subculture) in Beijing. A couple of others then do the same. I am happy to register that no one objects to us being present and taking notes. The moderator then proceeds by suggesting participants say a few words about what issues they consider important in gay ‘health education’. The evolving list in my notebook is a long one: self-acceptance (ziji rentong), safe sex (xinganyuan), telephone and online hotlines, family and parental pressures (including marriage pressure), human rights and legal recognition for queers (most speakers here use the term tongzhi), same-sex and lala-gay convenience marriages, relationship problems, queers and old-age issues, gender issues for lalas, to come out (chu gui) or not to come out, workplace pressure to conform (marry and have family), and the difficulty of organizing queer events on university campuses due to official censorship. The list goes on, and so does the debate this morning. We pause at midday for lunch, a welcome break to catch up with friends, talk about the evening before, but also to reflect on the morning’s meeting. The table is buzzing with conversation between participants from wildly different backgrounds and identifications. I chat with Qiaohui, a likeable and forthright lala in her forties whom I know well, and a young European research student about the differences between lala and gay health issues. We almost forget about the start time of the afternoon session and have to run to reclaim our seats.

When I finally returned home to the welcome solitude of my apartment in downtown Beijing that evening, my notepad was full of notes from a weekend of intense encounters and conversations. I set to work on my laptop while impressions and events were still fresh. By this point, this type of eventful weekend fieldwork had become regular practice, and I often faced the enviable problem of having to choose between overlapping events and invitations as new networks and circles of friends organized parties, dinners, outings, trips, conferences, and workshops. Back in September 2004, when I first arrived in Beijing for fieldwork, the situation was very different. There was only one bar for women patrons, the downtown Feng Bar (often called Pipe, its daytime café name). The manager was lala, but Saturday was the only night reserved for women-only. There were no support groups or organizations dedicated to lalas. There were private networks of friends and online discussion forums, but they were very much divorced from a sense of ‘real’ community in Beijing’s vast cityscape. However, things changed rapidly in the 2004–2006 period. As I completed the revisions to this book, I was reminded of the energy and drive of the lala community at this time, the explosion of ideas and opinions, the experiences I had, and the fundamental paradox of defining the lala (and gay) community: on the one hand, new freedoms and opportunities for social activism, leisure, and intimacies were unfolding; on the other hand, the powerful and creative combination of preexisting social and familial norms and political authority shaped and severely limited the development of such communities, rendering their practices and imaginaries precarious and making them spatially and economically marginalized.

Beijing Lalas: Paradoxes, Normativity, and Modernity

Queer Women in Urban China is at once an ethnographic account of lala lives in Beijing’s postmillennial period and a critical anthropological analysis of new forms of sexual subjectivity and identity-based community in the context of rapid socioeconomic change and intense urbanization. The post-Mao era (since 1976) has seen reforms of a scale and speed that is unprecedented in the modern world. Much scholarship to date has been concerned with chronicling the dramatic transformations in terms of how everyday people’s lives are affected, their perceptions of self and identity, considerations of what is lost and gained, and questions of the moral good and bad when living through times of great change. The main story is one of hope and opportunity: millions of people lifted out of poverty, urban prosperity, greater personal freedom, emerging civil society, and opening up to the outside world. But there is also a more sinister subtext here that has become more evident in the new millennium’s second decade. It is one of strict political authority circumscribing liberating and progressive processes, and a rigid system of social and familial norms that continues to define dominant ideals pertaining to family, gender, and desirable Chinese culture writ large. What emerges is a paradoxical picture of change and continuity, freedom and constraint, modernity and tradition that profoundly shapes people’s sense of self, society, and the position of China in the world.

In order to address lala lives and community cultures against this complex background, this book develops an ethnography-based analysis of the subjective, social, and political processes of “becoming differently modern” (Knauft 2002: 3). It draws on interdisciplinary scholarship of everyday experiences and new sexual and gendered subjectivities in China, anthropological studies of post-Mao transitional China, and anthropological literature on nonnormative sexuality and gender diversity in a transnational perspective. The research is grounded in the study of individual and collective lala lives in Beijing, China’s bustling capital city. The data sets informing the analysis are anchored in anthropological fieldwork undertaken between 2004 and 2006, further shaped by return visits in 2009 and 2012, as well as ongoing involvement with activist networks and analysis of relevant social media.

The temporal specificity of the study is significant to the arguments put forward in the pages that follow. As such, this book does not intend to present a generalized or timeless picture of ‘lesbians in contemporary China’, or indeed of ‘sexual revolution’, or to make definitive claims about absolute liberatory progress in the more than thirty years since the end of the Maoist era—from repressed and invisible to ‘open’ and liberated, for example. Placing the primary temporal focus on 2004 to 2006 allows scrutiny of a particular period of relative political permissiveness and relaxed official censorship and control in Beijing, a focal point for new lala and gay communities and discourses in the country.2 In contrast, earlier initiatives in the 1990s were largely secret and private, socially invisible, or attached to official public health and HIV/AIDS programs driven by government policy that severely limited the growth of community-defined needs. Women were close to invisible during this early period. Later attempts by women to organize, toward the end of the 1990s, were short-lived and ended abruptly when political authorities shut down a lesbian community festival in 2001 and intimidated its organizers (Wang 2004). With wider access to the Internet in urban China, alongside the emergence of informal and semipublic spaces for alternative groups and minorities, gay and eventually also lala community spaces consolidated in the early 2000s. With hindsight, I would argue that the early 2000s, up to the 2006–2007 pre-Olympics period, represented an extraordinary window of liberating opportunity that has since been more or less closed by the government’s reactivation and intensification of restrictive policies. This does not mean that lala and gay subcultures have since disappeared—far from it, as later chapters in this book will argue.

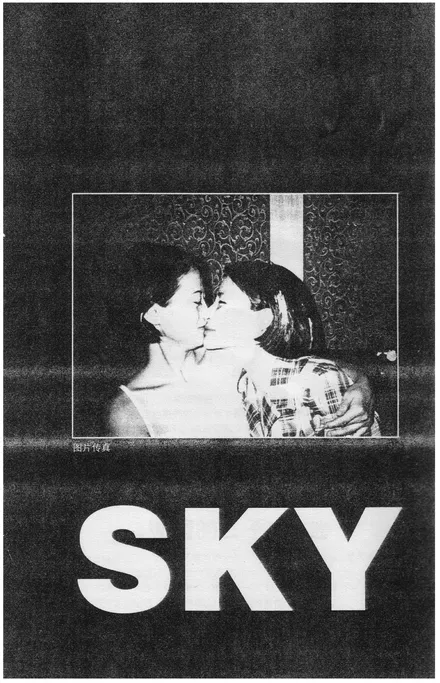

Figure 1.2 Tiankong (Sky) magazine cover, by Beijing Sisters, 2000.

For Beijing lalas and their community organization the early millennial years saw the emergence of two social networks—the Lala Salon and the Tongyu group. Both have continued to grow and consolidate support and participation for lalas as well as their gay, trans, and straight allies in Beijing, across China, in the Asian region, and, indeed, worldwide. It is in part this opportunity for “spaces of their own”, to paraphrase Mayfair Yang (1999), that I trace the significance of in this book. What does it mean to feel differently and take steps to seek out intimate relationships as well as an offl ine, reallife community of others like oneself? How do processes of sexual subject formation and an emerging sense of social identity around new vocabularies of sexual difference and sameness become personally and socially meaningful in a country where homosexuality remains a social taboo, and public recognition is at a minimum? Following feminist and lesbian anthropology’s persistent call for gender analysis in studies of same-sex sexuality (Lewin and Leap 2002; Sinnott 2009; Wekker 2006), I ask about the broader transformations in gender norms that have opened up socioeconomic and symbolic possibilities for more women to seek out same-sex relationships and communities. In so doing, I address the issues of rising social, and to some extent public, visibility and the degree of popular acceptance of homosexuality in general and lesbianism in particular in China.

I track how expansion of semipublic social space and changes in the private/public dynamic in the reform period are enabling sustained lala social initiatives beyond virtual space, and why semiprivate community activities retain more popularity than identity-based movements and organized activities focused on rights activism. As Megan Sinnott has argued, it is important to question the gendered coding of urban/public space as implicitly masculine and “the site of liberation and sexual fulfillment,” and consider more critically the “gendered specificities of culturally constructed spatial use” (Sinnott 2009: 236; and see Gray 2009). The chapters that follow consider this question closely, and pay particular attention to the coconstituent factors of age, marital status, family relationships, and socioeconomic status, including level of education. Drawing on David Valentine’s illuminating ethnography of the transgender category (2007), I appropriate lala as a social category rather than an individual sexual identity similar to ‘lesbian’, which is constituted by a range of factors, including those mentioned earlier (see Chapter 2).

By focusing on lala lives in this particular time period, and providing a broad examination of intimate and collective lala lives, this book aims to capture a fragment of a historical moment when changes and continuities coexisted in particular ways, when same-sex ideologies and aspirations began to be assertively articulated in the collective language of ‘lala’ and ‘community’, and spatial locations emerged that were significantly different from previous times. At the same time, the book also shows that the lala community practices that developed during my research period were extensions of earlier shorter-lived initiatives in the 1990s. Collectively held memories of this period—often iterated in online discussion forums and offline socializing in long-standing informal networks—served as crucial reminders, learning resources, and ideological inspiration for emerging community organizers and current participants. Through these practices, memories, and aspirations, lalas were of course also looking to the future, in seeking to shape it and create better conditions for themselves and those coming after.

Queer Women in Urban China also builds on recent queer Asian studies and queer China studies to develop a grounded analysis of the study of sexual and gender nonnormativity in urban China from a queer-feminist anthropological perspective. Central to the analysis is a critical examination of tensions regarding the position and experience of normativity and ‘being normal’ versus the queer validation of difference and transgression. Similarly, in my focus on lalas, I highlight the role of gendered status and personal agency in the context of socioeconomic reforms and globalization. More specifically, I am interested in the powerful ways that hegemonic social and familial norms continue to define girls’ and women’s scope for meaningful independence and agency. In turn, this is happening in a time and place where discourses of modernizing progress, individualization, and the (relative) retreat of the state have assumed primacy. On this basis, I focus on how personal and social narratives of choice and freedom (to be normal, to have same-sex relationships, and so on) are situated by broader personal and social contexts in which such statements are becoming desirable. I ask, how do same-sex-desiring women negotiate new opportunities for making personal and individual choices against the backdrop of the preexisting dominant social norms that value family and filial responsibilities? In what ways are women experiencing and developing a meaningful vocabulary of choice and strategic practices in the context of emerging sexual identity categories and communities? What meaning-making processes are women with same-sex desires developing in order to (try to) balance normative and alternative definitions of gender, sexuality, and ‘the good life’?

Queer Paradigms and Different Normativities

In offering a critically grounded and empirical analysis of lala subjectivities and lifeways in China, this book engages central debates in interdisciplinary queer and gender studies, including the subfield of queer anthropology (see Boellstorff 2007). Some of the important questions that drive these debates are whether queerness is necessarily or inherently transgressive and disruptive of normalization regimes; and the extent to which aspirations for 'normalcy' and respectability, the mainstreaming of sexual identities and lifestyles, and negotiation with the social and institutional conditions that shape all lives carry transformative power (see, for example, Warner 1999 and Wiegman 2012 for insightful theoretical discussions; and Boellstorff 2005; Gray 2009; Wekker 2006 for valuable ethnographic analyses).

One influential paradigm underpinning contemporary queer and gender studies and activist discourses implies Euro-American urban locations as points of reference and origin, resists normativity and assimilation strategies, and considers conventional kinship and family forms based on reproductive heterosexuality to be the antithesis to authentic queer life. In its stead, as for example noted by Carlos Decena (2008) and Martin Manalansan (2003), it validates and celebrates confrontational and ...