![]()

1 Introduction

Some lingering social problems like crime, drug use, prostitution, child abuse, and illegal migration share an important characteristic: they are likely to provoke popular anxiety and moral outrage. Across space and time their occurrence varies, yet quite often the levels of popular anxiety and outrage do not vary with evidenced trends in the expected way, namely growing with upward trends, remaining stable with unchanging trends, and declining with downward trends. In fact, it is not rare for popular perception of a growing problem to occur despite evidence of downward trends. For criminologists, this gap between popular perceptions and reality, between fiction and evidence-based research findings, is a well-known recurrent social situation, and they generally point out the negative consequences of such misperceptions for both good theory and legislation (Weitzer 2012).

Numerous studies of popular opinion about the prevalence and seriousness of crime reveal consistent findings: people believe that violent crime is far more prevalent than what is measured by both police statistics and crime victim surveys, and they tend to see a growing crime problem when the trends indicate otherwise. Because, or as a consequence, of the anxiety and outrage provoked by these problems, the latter are also dramatized, glamorized, and sensationalized in newspaper articles, movies, and TV shows that select the most fear-provoking and outrageous cases for popular consumption. The sobering findings of serious evidence-based criminological studies would be expected to reduce misrepresentations and misperceptions, yet at times, in spite of all evidence, these misrepresentations and misperceptions reach vertiginous proportions. When such a situation arises we are facing a moral panic.

Human trafficking has been likened by the United Nations (UN), the United States (US), other Western governments, and many non-government organizations (NGOs)1 as “modern-day slavery.” It has been presented as a transnational enterprise controlled by organized crime, which enslaves 12.3 million people, generates $32 billion in profit for human traffickers, and poses a serious threat to national and global security. While these alarming claims have received little support from the scarce empirical literature on human trafficking and the handful of studies on traffickers, the world, and with it Cambodia, has been called on to wage a “war on human trafficking.”

This book seeks to answer two broad questions: first, why and how, in the absence of supporting empirical evidence, such sensational claims prevailed, and second, why Cambodia suddenly in 1996 enacted an anti-trafficking law that is one of the harshest laws in the country, punished as severely as premeditated murder? Using a multi-method and multi-source research design, which includes police and prison records, interviews with police and prison officers, court officials, NGOs, villagers and migrants (altogether 466 individuals), and particularly 91 detained traffickers, the book investigates five major themes about traffickers in Cambodia: who are they, how do they operate, how much profit do they make, why are they involved in human trafficking, and how does the Cambodian Criminal Justice System (CJS) control their activities?

By using three levels of analysis this book offers a comprehensive theorization of the problem of human trafficking in Cambodia. At the global level, it examines the construction of human trafficking, by drawing on the notion of hegemony (Gramsci), the politics of immigration control, and the role of foreign aid and NGOs. It also addresses the influence of the politics of sexual morality informed by debates about prostitution between opposing abolitionists and sex-as-work feminists, and the organization of moral panics (Cohen 1973; Talbot 1999; Weitzer 2012).

At the national level, the concepts of “anomie” (Durkheim 1897) and “global circuits of survival” (Sassen 2002) are used to analyze the problematization, occurrence, and criminalization of human trafficking in Cambodia. Both approaches suggest that drastic and rapid societal transformations lead to anomic periods during which deviance increases, but Sassen’s perspective has the advantage of being placed in the context of globalization and articulated around the situation of women from the developing world in this new context. This level therefore investigates the socioeconomic, political, and cultural contexts associated with human trafficking in Cambodia.

At the individual level, the motivations and behaviors of human traffickers and Cambodian law enforcement agents are investigated drawing from “strain theory” (Merton 1968), along with the notion of the “feminization of survival” (Sassen 2002). Both Merton and Sassen use the notions of push and pull factors, which Merton articulated as the interplay between blocked legitimate opportunities and the presence of illegitimate opportunities to achieve valued goals. However, as noted before, Sassen’s context is the situation of women from developing countries in the globalized new world order, thus particularly suited for this research. Perspectives on organized crime, classical theories of law and deterrence (Beccaria) and modern theories of the behavior of law (Black) have also helped in the analysis of the individual level.

In the Cambodian context, this research does not support the popular claims about the high prevalence, profitability, or role of organized crime in human trafficking. Incarcerated human traffickers in Cambodia are poor, uneducated individuals, and 80 percent are women. Their activities are unsophisticated and conducted by sole operators or small casual networks. Pushed by a lack of legitimate opportunities and pulled by the presence of illegitimate opportunities, to survive they engage in human trafficking for very modest gains. Caught in a corrupt criminal justice system, they serve long prison sentences and as many as 60 percent are probably the victims of miscarriages of justice.

My personal journey

I had been working for six years in NGOs when, in 2005, I became the National Project Coordinator of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). One of my responsibilities was to provide technical assistance to 15 partner NGOs receiving funds from my project to help victims2 of human trafficking3 through programs addressing the recovery, rehabilitation, and reintegration of survivors of child trafficking in Cambodia. It was a particularly challenging mission because at that time my knowledge about trafficking was very limited. However, my colleagues were supportive. They shared their understanding of human trafficking in Cambodia with me, and I read many reports to familiarize myself with the issue.

My sources of information were essentially NGOs’ reports, documents, and anecdotes based on the perspectives and experiences of some trafficked persons and their helpers. This literature painted a horrific picture of helpless victims and ruthless traffickers, which convinced me that trafficking in Cambodia was a serious social problem to be urgently addressed. During my first six months in the Project, I talked to NGO workers, villagers, and local authorities in trafficking-prone areas, and former trafficked persons living in NGO shelters or who had been reintegrated into their family or community of origin.

In 2006, I did a small study of 17 children4 who NGOs that helped them claimed had been “child victims of cross-border trafficking.” I interviewed the children after they had left NGO shelters and been reintegrated into their family or community (Keo 2006). I did a limited review of the local literature and conducted semi-structured interviews with nine boys and eight girls who had been “trafficked” to work in Thailand. To my surprise, none of them saw themselves as “victims.” They had willingly followed their recruiters to Thailand to earn an income and support their impoverished family. Instead, they considered themselves heroes and heroines, and models of good children for their ability to work and share the burden of supporting their family. Most had been “trafficked” by their families, relatives, or neighbors, and a few by strangers. Few had suffered physical abuse. In fact, most of them had been treated well. From their accounts, human trafficking did not sound like a risky activity, and traffickers did not make particularly big profits.

These findings contradicted most of my previous understanding of the phenomenon, and raised many questions about traffickers in Cambodia. Who were they? Why were they involved in trafficking? How did they operate? Was trafficking in Cambodia as profitable as it was said to be, and was it really such a serious problem as many were claiming? I started reviewing the trafficking literature and discovered that very few studies focused on traffickers and that none had been interviewed.5 Puzzled by my discovery, I talked to staff of NGOs that worked on counter-trafficking activities, but none of them had ever talked to a convicted or suspected trafficker. If no empirical study on traffickers had been conducted, did the available reports on trafficking and traffickers constitute reliable accounts of the problem? Was it possible to properly comprehend and address human trafficking without a thorough understanding of the offenders?

I wrote a proposal to conduct a small empirical study of traffickers in Cambodia. It would have been the first attempt, at least in Cambodia, to interview trafficking offenders. I sent the proposal to my supervisor, the former IOM-Cambodia Chief of Mission, but received a negative response. The idea, he said, was good but everyone felt it would not be feasible and would put me at great risk because traffickers are very dangerous individuals. Without his authorization, I could not embark on my initiative. It was disappointing, but I did not give up. I had a conviction that the best way to understand offenders is to directly study them. In this respect, I was inspired particularly by the work of Zhang and Chin (2002, 2004) who attempted to understand “human smuggling” from the smugglers themselves and had been able to interview 129 suspected Chinese smugglers. This persuaded me that it would be possible to invite active or incarcerated “human traffickers” in Cambodia for interviews. My determination was rewarded. In 2007, I was awarded a PhD scholarship,6 allowing me to conduct this challenging but important and exciting study.

A global human trafficking moral panic

In the early 1990s, the end of the Cold War and the globalization of economic activities engendered important movements of people from the third world to western European countries, the US, and other developed nations. Pushed by socioeconomic hardships and troubles at home, and pulled by the prospect of a better livelihood in the West, many people from the developing world attempted to reach the developed world through the new global channels of migration (Massey 2003; Rao 2011). The Western world, concerned about security, the protection of labor markets, and cultural values, engaged in an increasingly intensified campaign against illegal migrations and those who facilitated them, a new breed of “international criminals:” the people smugglers (for instance, see Jackman 2011). During the same period, governments and elements of civil society in the West, particularly in the US, “discovered” a related but even more alarming threat to humanity and the global order, a threat spreading like an epidemic: human trafficking. This new “social disease,” however, was reminiscent of the old “white slave trade” that had panicked the West at the beginning of the twentieth century, and is presented today as “modern-day slavery.”

Moral entrepreneurs (Becker 1973)7 with various agendas represented in six common counter-trafficking approaches (moral, demand, labor, migration, organized crime, and human rights) joined their voices in the accelerating human trafficking panic. Foreign NGOs and aid donors influenced the design and adoption of the Cambodian anti-trafficking legal framework, The Law on the Suppression of the Kidnapping, Trafficking, and Exploitation of Human Beings (The 1996 Anti-Trafficking Law) in particular. The latter was poorly written, ambiguous, confounded trafficking, smuggling, illegal migration, and prostitution, and cast a wide net over many ill-defined behaviors.

All this was happening in a country just emerging from 30 years of armed conflicts, including the genocidal regime of the Khmer Rouge during which around two million Cambodians died, still grappling with high levels of violence, where poverty and social inequality were widespread, the criminal justice system weak and corrupt, the police and judiciary poorly trained and paid and known to systematically engage in rent-seeking and extortion. This anomic period in Cambodia was embedded in a larger, more global wave of change brought about by globalization, and itself generator of anomic conditions. The new rules of this transnational, globalized game created both legitimate and illegitimate opportunities in “global circuits of survival” (Sassen 2002). Through these circuits, women of developing countries like Cambodia increasingly moved abroad to try and make a living, and become exposed to the risk of being exploited and abused, including criminalized.

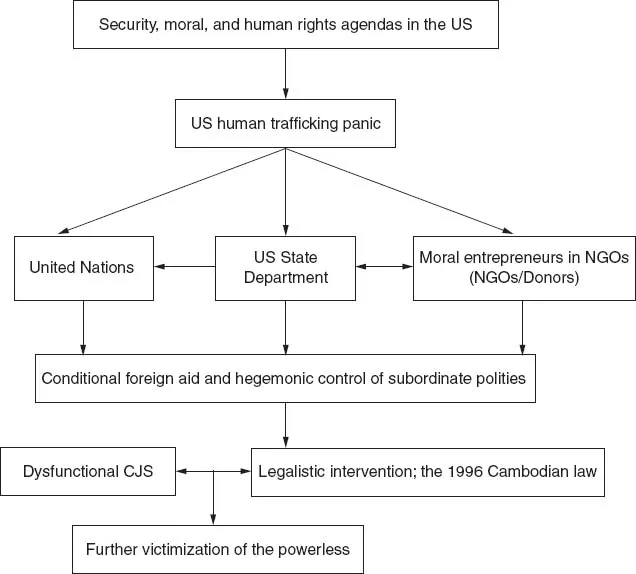

Figure 1.1 summarizes my attempt at making sense of my findings and answering two major questions: Why, when alarming claims have received little support from the scarce empirical literature on human trafficking, including the handful of studies on traffickers, the world, and with it Cambodia, has been called to wage a “war on human trafficking” and suddenly in 1996 enacted an anti-trafficking law that is one of the harshest laws in the country, punished as severely as premeditated murder? In a nutshell, I argue that the hegemonic security, moral, and human rights agendas of the West initiated a security and moral panic about human trafficking. Pressured by foreign and local NGOs and the need for foreign aid, Cambodia adopted a repressive legalistic response. In the hands of a problematic criminal justice system harsh laws did not deter potential traffickers but produced serious unintended consequences that turned the law into an instrument of corruption and injustice against the powerless.

Figure 1.1 Human trafficking and the hegemonic enterprise.

The term “hegemonic enterprise” in the title of Figure 1.1 requires some introduction. “Hegemony” originates from the Greek word hegemonia, meaning “leadership” (Bates 1975; Smith 2010). Gramsci used the concept to refer to the ability of the dominant class to exercise power by winning the consent of those it dominates, as an alternative to the use of coercion. It is a process of moral and intellectual leadership where consent-based domination is secured through the injection and universalization of the moral, cultural, and political values and agendas of the ruling group (Bates 1975; Cox 1981; Mastroianni 2002). Over time, these views become so widespread, so much part of an imagined “natural order,” that the dominated groups accept them unquestionably. In other words, the values and agendas of the ruling groups become “common sense.” The basic premise of the theory of hegemony, therefore, is that people can be ruled not only by force but also by ideas and deceptions (Bates 1975).

Neo-Gramscian perspectives emphasize that the establishment of hegemony by leading groups occurs first within a specific state, and it is then transported outside its border (Bieler and Morton 2004). ...