- 410 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

An integrated guide to the entire range of clinical art therapy. Its scope is immense, covering every age range in a variety of settings from schools and outpatient clinics to psychiatric hospitals and private treatment. Of special value are the extensive case studies and 148 illustrations.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

An Overview

CHAPTER 1

Introduction to Art Psychotherapy

This book presents a working model for clinical art therapy or art psychotherapy as it is practiced by the author. Major emphasis is placed on the dynamically oriented art therapy theory which was formulated by Margaret Naumburg (1966).

Although a neo-Freudian frame of reference is at the base, the reader will find a flexible and often innovative approach is utilized to meet the needs of the client. The chapters herein display a conceptualized approach, accompanied by illustrations of its application through the case material and artwork of populations ranging from latency age through geriatrics. The focus of art therapy may vary due to the treatment setting; therefore, this text introduces methods which are pertinent to a variety of environments, including outpatient settings (clinics, schools, geriatric centers, rehabilitation programs and private practice), psychiatric day treatment and inpatient units, and medical hospitals. Examples are given for individual, conjoint, family and group work during stages of prevention, brief crisis intervention, diagnostic evaluation and treatment.

The artwork presented demonstrates the effectiveness of clinical art therapy for gaining awareness, reality-testing, problem-solving, revealing unconscious material, catharsis, working through conflicts, integration and/or individuation. During each session the clinical art therapist offers techniques, subject matter, media and/or free choices which are pertinent to the changing needs and therapeutic goals of the client. The individual may make a conscious choice of what to convey through the artwork or may begin in random fashion; he or she may work on a particular topic suggested by the clinician. Directives given may be in the realm of general or specific themes, such as emotions, wishes, dreams, fantasies, plans, self-images, family constellations, environments, situations, etc.

The nonverbal aspect of art psychotherapy holds an important and unique position in the realm of mental health work, for it gives the clients an opportunity to listen with their eyes. This is especially significant in our current society, where we are constantly bombarded by speech through personal contact and the communication media. The common tendency of individuals to “tune out” what they prefer not to hear makes the visual image a powerful tool for treatment.

Clients are introduced to clinical art therapy by being informed that this method is used to help them better understand themselves and how they function as individuals and/or part of a family or a group system. Participants are purposely involved with simple art media to facilitate creativity and to lessen superego demands on performance. The art psychotherapist provides materials which have a direct relationship to immediate and/or long-term treatment goals. The size and particular properties of the media are also factors which may have an effect on the patient’s emotional state and adaptive mechanisms. Using the art supplies requires no technical skill. Most commonly used are oil pastels, felt markers, watercolors, tempera and acrylic paints, plasticene, clay, tissue paper and magazine images.

Art products can be interpreted from several frames of reference, such as Freudian or Jungian, according to the therapist’s orientation. However, it is essential to understand the client’s own interpretation. The author believes in individual symbology, which may change during various life cycle stages. For instance, a “clock” has different meanings: To a child it may represent time to go to school, eat, or go to bed; for the young adult its symbol may imply time to decide on a career, marriage, children, etc.; for the mid-life person, the clock may represent time to evaluate value systems, plan goals or make changes; the old person may see it as a symbol for completion or the end of life.

Both two- and three-dimensional art forms frequently make a tangible statement about the client’s hidden emotions, thoughts, or mode of functioning. This is due to the participants’ new experience in communication where they are detached from their usual defenses. Although this aspect of art therapy has a special value in treatment, precautionary measures must be taken when repressed material surfaces quickly; the therapist must evaluate which, if any, intrapsychic images the patient should work on. All too often the neophyte therapist plunges into intrapsychic evidence before having had time to pull back and decide on the “appropriate timing” for dealing with the displayed material.

A distinctive characteristic of clinical art therapy is the clients’ advantage of recording their own therapeutic process, through both the image and written commentary. Art therapists educate participants to write down thoughts, emotions and free associations which relate to their artwork. In cases of younger children, statements or stories are dictated to and written down by the therapist. This commentary adds to the patients’ ownership and responsibility for their own work in therapy. That the artwork can be reviewed at any time during the treatment or termination phase of therapy is a bonus. At the completion of therapy this procedure acts to reinforce gains and gives the art therapy participant a rite of passage experience.

The section on family art therapy illustrates the use of clinical art therapy for diagnosis and treatment. A clarification of the term “diagnosis” as it is used in this context is essential. In family treatment, diagnosis refers to the family system, that is, how the members function within their family unit, the role each person plays, methods of interaction, and family strengths and weaknesses. Family art therapy is often task-oriented; the family creates art products together, sometimes nonverbally and other times with discussion. The process is observed and explored by the family and summarized by the art psychotherapist. The mutual art forms provide a platform for understanding and strengthening communication skills. They become the microcosmic trials for improving family relations.

In the following sections of the book experiences in working with group art therapy within various age categories are presented. Regardless of the age group involved, participants work on interpersonal and intrapsychic material. Communication is encouraged through the art therapy format, with group members expressing and sharing themselves both visually and verbally. This procedure is especially helpful to persons who have difficulty in asserting themselves in a group and is effective in therapeutically limiting the overly aggressive participant.

Groups in outpatient settings are composed of populations which are heterosexual or the same sex, contain peers or cross-generational individulas, include specifically unrelated persons, or couples, or families. Some groups are formulated around specific issues, problems or symptoms. They may be composed of single-parent households, intact families, families with a chronically ill member, and so on. In such cases, the art is created around the issues relevant to the population. The art therapy format has also been used for consciousness raising and for data collection and assessment.

In the day treatment or partial hospitalization program, group art therapy serves a major function of resocialization. Cooperative art tasks are specifically designed to desensitize the individual to group process and serve as a nonthreatening method for decision-making and interpersonal contact.

Within the psychiatric hospital setting, the art therapy groups are often thematically oriented to reveal the individuals’ and group’s strength. Concrete tasks help patients connect to their internal problems, with a special emphasis on external realities.

There are many nonclinical settings which offer mental health services, including public schools, residential centers, medical hospitals, physical rehabilitation programs, pain centers, camps, churches, youth centers, geriatric centers, etc. In these environments art therapy is utilized with emphasis on self-expression, improvement of communication, socialization and rehabilitation skills.

The clinical art therapy approach affords a wide source of variations and goals; therefore, it is an accepted therapeutic modality wherever mental health services are offered. Several chapters in this book describe the use of art therapy within the nonclinical settings.

ILLUSTRATIONS

To briefly acquaint the reader with some of the issues which are dealt with through clinical art therapy, simplified examples from case histories are given in this introductory overview.

Diagnosis

The onset of clinical art therapy includes a diagnostic evaluation. In addition to the verbal developmental history, art tasks are an important part of the assessment. The psychotherapist’s observation includes: the client’s approach and process; the product in relationship to form, space, color and composition; content, attitude and physical response to the art materials. All of these aspects are essential factors in diagnosing the client and in making treatment recommendations to suit the need of the individual.

During the evaluation period, Mr. Stockton used the collage media. He selected pictures by looking them over one at a time, then neatly placed various subjects in separate piles. The choices were devoid of people; the image of a tree with dying leaves was carefully trimmed around the leaves in an attempt to “do it perfect.” The other pictures included a desolate desert and a junkyard. The client placed six dots of glue on the back of each picture. He became upset when a drop of glue touched his fingers. Mr. Stockton placed the pictures very carefully on the page, trying desperately to have them pasted at equal distance from each other. When asked to write a statement under each picture, he expressed his desire for a ruler so his printing would be even in size. Mr. Stockton’s low frustration tolerance was exposed when he swore as an edge of one of the pictures curled away from the paper.

One picture does not provide conclusive evidence towards any diagnosis. However, the media and procedure lent themselves to giving clues important for the evaluation. The man’s ritualistic method of dealing with the media, low frustration tolerance, extreme concern around cleanliness, refusal to touch wet glue, avoidance of human subjects (in view of the fact that these were available in the vast majority of pictures), the lifeless manner in which he selected the pictures and their placement on the page—all offered the evaluator a great deal of material in a very brief length of time. The question of an obsessive-compulsive personality was later confirmed by the manifestation of analogous rituals, attitudes, and reactions in daily life.

Assessing Family Systems

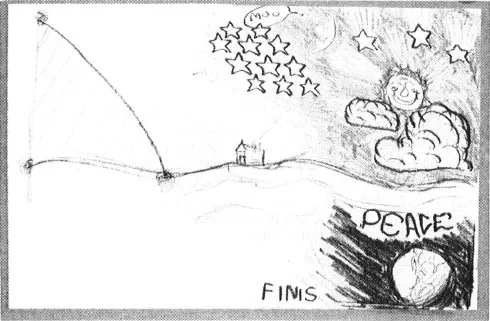

Families can improve their communication when they discover how they function as a unit. A family with a teenage son was instructed to draw a picture together (Figure 1). The procedure included the parents’ instructing their child to start the picture by doing whatever he pleased. He immediately drew a horizon line, then took a long time to fill up the entire right side of the page. The father went next to draw a sail on the left side of the paper, leaving a void in the center of the page. The last turn was taken by the mother, who drew a very tiny house in the middle.

During the discussion, the parents expressed anger towards their son for taking up so much space and time. They had forgotten their statement to him to do as he pleased. With the psychotherapist’s help they began to realize they had set no limits, yet their expectation was for him “to take up less space.” Mother, feeling terribly upset, explained that there was no room left for her after her husband and son took over so completely. She said it was necessary to squeeze in her tiny house. When confronted with the picture itself, it was obvious there was plenty of space; she could have drawn larger. Father had also felt left out; after he examined the artwork he was utterly surprised that he had taken up much more room than his wife. The boy thought that everyone was “equal”; he had taken it for granted that his parents, like himself, “had thoroughly enjoyed” drawing the picture together. The family realized that their individual perceptions of the process differed greatly. They had projected preconceived ideas and emotions onto the artwork.

Figure 1. Family drawing displays dynamics

The art task orientation gave the art therapist and the family a vehicle for understanding how the family functioned as a unit.

Ongoing Diagnosis: Reflection of Family Life

In the House-Tree-Person projective test, Hammer (1971) postulates the house represents an individual’s psychological response to the family situation. Ira Styne, a 10-year-old boy, performed poorly in school in spite of a high IQ. He was rejected and scapegoated by his family and peers for his provocative behavior. In clinical art therapy he created a great many clay houses...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Illustrations

- Part I. An Overview

- Part II. Family Art Psychotherapy

- Part III: Latency-Age Children

- Part IV. Adolescents and Adults

- Part V. Aged Adults

- Part VI. Psychiatric Hospitals and Day Treatment Settings

- Part VII. Rehabilitation and Treatment of Chronic Pain

- References

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Clinical Art Therapy by Helen B. Landgarten in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Mental Health in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.