This is a test

- 436 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

There is no simple threshold between the experience of drinking and the pleasure it can bring on the one hand and the pain and suffering caused by alcohol abuse on the other. But if we are to understand the role of alcohol in society, then at the very least we need to acknowledge the pleasure as well as the pain. Alcohol and Pleasure aims to bring together existing knowledge on the role of pleasure in drinking and determine whether the concept is useful for scientific understanding and policy consideration.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Alcohol and Pleasure by Stanton Peele, Marcus Grant in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Applied Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Pleasure and Health

The idea that pleasure has public health significance is a novel one, but not without precedent. Healthful aspects of drinking have been noted historically and cross-culturally since antiquity, as reported in Part 2. Current evidence and policy implications concerning the healthfulness of drinking are treated in Parts 3, 4, and 5.

In this first part, David Warburton compiles evidence from epidemiology, immunology, and other medical sciences that pleasure contributes to health. In making this case, Warburton describes pleasure as a fundamental biological mechanism. Michael Daube explores the concrete uses of pleasure in public health. Daube, like Warburton, sees the resistance to pleasure by health specialists as a cultural blind spot, one that makes health policy and education less effective than it otherwise could be. John Luik presents the opposing point of view that government should be excluded from decisions about individual health behaviors, just as modern society has moved towards excluding government from decisions about personal pleasure. Luik's and Daube's opposing positions stimulated considerable discussion and disputation at the conference, as reflected in the rapporteur's report at the end of this section.

Finally, Norman Sartorius broadens the conception of pleasure by relating it to its cultural, familial, social, and personal meanings. Although Sartorius stresses the relativity of the concept of pleasure, his long involvement in the field nonetheless points for him to the importance of pleasure as a consideration in public health.

Chapter 1

Pleasure for Health

David M. Warburton

This chapter summarizes evidence of the positive contribution of pleasure to individuals' health and so to the quality of everyday life (see also Warburton & Sherwood, 1996). The evidence comes from anthropology, neurochemistry, oncology, psychology, psychoimmunology, psychoendocrinology, and psychophar-macology.

For the anthropologist, pleasure must be seen as a subjective experience, because ethnic and cultural groups enjoy different things. It is also, however, a common experience and is part of the emotional vocabulary of all cultures (Tiger, 1992). This commonality among cultures indicates that pleasure is a universal human phenomenon.

From the viewpoint of psychology, pleasure has three components: (a) anticipation or the expectation of the pleasurable experience, (b) the pleasurable experience itself (often fleeting), and (c) retrospection. Recall of the pleasurable experience is often the most potent of pleasurable experiences and can be thought of as scanning the scrapbook of the mind.

Viewed from a psychopharmacological perspective, pleasurable experiences are clearly emotional states that map onto a neurochemical state in the brain. Studies on the neurochemistry of pleasure suggest that all pleasurable experiences can be related to the same neurochemical systems of the brain. There are two main strands of evidence for this proposition.

First, all pleasures can be lost under certain pathological conditions and then regained with treatment by certain types of drugs. One pathological condition marked by the loss of pleasurable experience is depression. Depression occurs in all cultures and is defined by a standard set of symptoms (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Not all of these symptoms occur in every depressed individual, but a person is considered to have a major depressive episode if he or she exhibits a loss of pleasure in all, or almost all, usual activities. The universality of the pleasure loss by persons suffering from depression in all activities (from sexual activities and social interaction to musical and intellectual pursuits) suggests mediation by a common brain system.

Second, drug treatment can reinstate all the personal pleasures of an individual, whatever they may be. The restoration of pleasure in all typically pleasurable activities supports the notion of a common neurochemical system or systems for all pleasures. Thus, the only difference between brain states for pleasurable acts is quantitative.

Although there is a vast literature showing that negative psychological states are deleterious for physical health, the words “pleasure” and “happiness” are almost totally absent from the medical vocabulary. It is becoming clear, however, that pleasure is essential for physical and mental health. Pleasure can proac-tively promote good physical and mental health and protect against ill health, that is, serve as inoculation. Pleasure also can aid the process of unwinding, thereby lowering levels of stress hormones and protecting against potential adverse effects on the body. In this manner, pleasure acts as antidote against past stressors.

NEGATIVE PSYCHOLOGICAL STATES AND HEALTH

A good deal of evidence exists on the association of negative psychological states with ill health.

Stressors

Studies have shown a 259% increase in illness episodes following the onset of stress episodes in comparison with what would be expected by chance (Rogh-mann & Haggerty, 1973). This reactivity to stress increases, for example, the likelihood of childhood respiratory illnesses (Boyce et al., 1995). Similarly, other research has shown that children's life-event stress is associated with a longer duration of illness (Boyce et al., 1977). An important study has shown that stressor levels prior to inoculation with the common cold virus are positively associated with the onset of the symptoms of an upper respiratory infection (Cohen, Tyrrell, & Smith, 1991). This finding has been replicated in a smaller study (Stone et al., 1992).

Interestingly, the measure of life-event stressors in this research predicted infection symptoms, whereas negative affect and perceived stress levels predicted infection incidence (Cohen, Tyrrell, & Smith, 1993; Totman, Kiff, Reed, & Craig, 1980). The symptoms of upper respiratory infection cause people to seek medical help and to buy medication, but it is the incidence of infection that determines the size of the pool of contagious individuals and thereby the spread of infection throughout the population.

Although the acute stressor of parachuting decreases the number of natural killer cells (Schedlowski et al., 1993), more chronic stressful life changes actually reduce natural killer-cell activity (Locke et al., 1984).1 Relatedly, familial caregivers for patients with Alzheimer's disease have weaker immune systems, as shown, for example, by an enhanced antibody response to the Epstein-Barr virus antigen (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 1987); this reduction in immunity predicts adverse health consequences in the long term (Kiecolt-Glaser, Dura, Speicher, Trask, & Glaser, 1991).

Anxiety

The anticipatory anxiety of examinations reduces the activity of natural killer cells and the number of helper T lymphocytes, which directly or indirectly defend the body against viruses. Such changes are a predictor of acute infections (Glaser et al, 1987).

Bereavement

There is depressed lymphocyte proliferation response after bereavement (Bartrop, Lockhurst, Lazarus, Kiloh, & Penny, 1977) and suppression of lymphocyte production in response to an antigen challenge (Schleifer, Keller, Camerino, Thornton, & Stein, 1983). Irwin, Daniels, Smith, Bloom, and Weiner (1987) examined immune function in three groups: (a) women whose husbands had died of lung cancer within the previous 6 months, (b) women whose husbands currently were being treated for lung cancer, and (c) a control group of women whose husbands were in good health. In line with previous studies, the first group—those recently widowed—had impaired natural killer-cell activity.

Depression and Immunity

Depression, whose defining characteristic is a loss of interest and pleasure in all activities, decreases natural killer-cell activity (Irwin, Daniels, Bloom, Smith, & Weiner, 1987). In comparison with control subjects, patients with major depression have more circulating leukocytes and granulocytes, fewer natural killer cells, and less natural killer-cell activity. As a result, these individuals are more susceptible to viral infections normally controlled by such activity (Bartlett, Schleifer, Demetrikopoulos, & Keller, 1995; Schleifer, Keller, Bartlett, Eckholdt, & Delaney, 1996).

Negative Mood State and Immunity

All of the psychological states described previously are extremes on the spectrum of negative emotions, but recent studies indicate that everyday negative moods also weaken the immune system. For example, Stone et al. (1994) demonstrated reduced salivary immunoglobulin-A antibody response to oral antigen challenge on days marked by negative mood states. In turn, low secretory immunoglobulin-A levels in saliva were found to be associated with frequent viral infections of the upper repiratory tract. In another study (Knapp et al., 1992), the induction of a negative mood state in healthy volunteers resulted in short-term suppression of the immune system. Mood induction was created by asking subjects to recall or imagine “the most stressful, disturbing, painful, turmoil-filled time or times you can.” The ensuing negative emotion produced significant decline in lymphocyte reactivity.

PLEASURE INOCULATION

There is an expanding literature on the effects of positive mood states on body systems, resulting in lower cortisol levels and increased immunocompetence.

Short Term

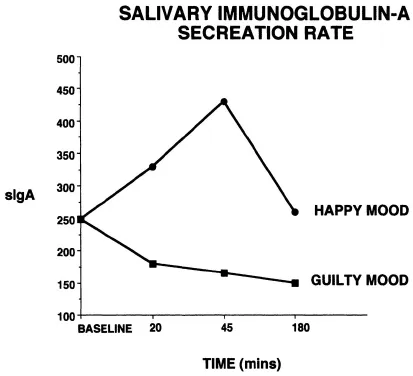

In the short term, techniques that promote relaxation have been demonstrated, for example, to produce a significant increase in natural killer-cell activity (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 1986). Mirthful laughter has been found to lower serum cortisol levels (Berk, Tan, Fry, et al., 1989), raise T-lymphocyte levels, increase the number and activity of natural killer cells, and expand the count of T cells that have helper or suppressor receptors (Berk, Tan, Napier, & Eby, 1989). Watching a funny film increases the salivary levels of immunoglobulin A (Dillon, Minchoff, & Baker, 1985), especially in those with a strong sense of humor (Lefcourt, Davidson-Katz, & Kueneman, 1990). In our laboratory, we asked subjects to recall either a happy autobiographical memory or one associated with feelings of guilt (n = 20 in each group). In the happy condition, subjects experienced an elevation of salivary immunogobulin-A secretion for 3 hours following the recall, guilty memories suppressed immunoreactions for a similar period (Figure 1.1).

Longer Term

As studies previously have demonstrated (Stone, Cox, Valdimarsdottir, Jandorf, & Neale, 1987; Stone et al., 1994), the salivary immunoglobulin-A antibody response to an oral antigen challenge is enhanced on days on which subjects experience a positive mood and lowered on days dominated by a highly negative mood. Moreover, the positive effect of pleasurable events on salivary immunoglobulin A has a 1- to 2-day carryover. Thus, it is not surprising that earlier studies had shown either an increase in unhappy events or a decrease in pleasurable events during the 3- to 5-day period prior to the onset of upper respiratory infection symptoms (Stone, Reed, & Neale, 1987).

Evans, Pitts, and Smith (1988) found a drop in the incidence of pleasurable events but not an increase in undesirable events prior to the onset of an upper

Figure 1.1 Immune response to “happy” and “guilty” autobiographical memories. Secretion rate refers to secretion over a 2-minute period as measured in micrograms per minute. The baseline (40 μg/min) is the prerecall baseline, that is, the “normal” baseline for individuals prior to laboratory testing.

respiratory infection. Evans and Edgerton (1991) found, by contrast, a decrease in happy events and a trend towards an increase in unhappy events in the days before an upper respiratory infection.

A provocative study about the influence of lifestyle in a random population survey in Northern Ireland (TV = 1787) collected samples of serum immunoglobulin-A, along with reported beverage-alcohol and cigarette consumption (McMillan, Douglas, Archbold, McCrum, & Evans, 1997). The population then was classified into the following groups: no beverage alcohol, 8 to 160 g beverage alcohol per week, 168 to 320 g beverage alcohol per week, and more than 320 g beverage alcohol per week (less than 8% of the sample). The median serum immunoglobulin-A concentrations showed a significant increase with beverage-alcohol consumption (p = .0001); subj...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- PART 1—PLEASURE AND HEALTH

- PART 2—PLEASURE AND ALCOHOL CROSS-CULTURALLY

- PART 3—ALCOHOL AND MEDICAL, PSYCHOLOGICAL, AND SOCIAL HEALTH

- PART 4—DRINKING EXPECTATIONS AND CONTEXTS

- PART 5—PLEASURE AND ALCOHOL POLICY

- Part 6— Conclusions

- Index