![]()

Mind the gap! European integration between level and scope

Tanja A. Börzel

Goods can be ‘integrated’ and maximized, so to speak, anonymously; the integration of foreign and military policies, in a world in which security and leadership are the scarcest of values, means what it has always meant: the acceptance by some of the predominance of others.

(Hoffmann 1964: 1275)

Introduction

Forty-five years ago, in his seminal book The Uniting of Europe, Ernst Haas laid the foundations for one of the most, if not the most, prominent paradigms of European integration – neofunctionalism. The book engaged in inductive reasoning to theorize the dynamics of the European integration process that led from the Treaty of Paris in 1951 to the Treaty of Rome in 1957.

The Treaty of Rome set the constitutional framework for a Common Market. Today, a second Treaty of Rome may lay the foundation for a European Constitution that embeds the Common Market in a European polity. Unfortunately, Ernst Haas will not be able to witness this path-breaking step in the development of a European political community, which he so aptly theorized almost five decades ago. This is all the more regrettable since students of European integration are more than ever challenged to tackle a major empirical puzzle: on the one hand, the acquis communautaire represents a unique degree of political integration beyond the nation state. The Common Market has been crowned with a common currency and consumers have been made citizens with their own fundamental rights and freedoms enshrined in a European citizenship and a Charter of Fundamental Rights. On the other hand, political integration in some sectors has seriously lagged behind. The Maastricht Treaty extended European integration to the last two bastions of national sovereignty: foreign and security policy and justice and home affairs. But the member states created a completely new set of institutions (second and third pillars) to keep the sectors off-limits to the Commission, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) and the European Parliament (EP). While the Amsterdam Treaty moved parts of the third pillar into the first pillar, the common foreign and security policy (CFSP) has remained under the exclusive control of the member states. Other examples of disparate integration are social welfare, culture and education policy, and economic governance. The European Union (EU) still lacks any substantial competencies in these areas. If the member states decide to co-ordinate their activities, they do so often outside the Community framework.

Why have the member states been willing to fundamentally compromise the core of their sovereignty in some areas (currency, citizen rights) while resisting any substantial cuts in others (security and defence, social welfare, culture and education)?

The explanation of what Ernst Haas (1958) called ‘task expansion’ is at the heart of neofunctionalist thinking (Haas 1958). Consequently, the expansive logic of sectoral integration constitutes the cornerstone of Haas’s theory of regional integration. The special issue revisits his works in order to explore whether neofunctionalist reasoning can still help us to understand and explain the dynamic process of task expansion in the EU.

The next paragraphs will outline the puzzle to be addressed by the various contributions to the special issue in more detail. The introductory chapter concludes with a brief road map to the edited volume.1

The Puzzle: The Disparity of European Integration

When analysing the evolution of competencies in the EU, many studies start with the Treaty of Rome instead of the Treaty of Paris. The foundation of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) in 1951 is hardly considered (Lindberg and Scheingold 1970; Schmitter 1996; Pollack 2000; Hix 2004). This is all the more regrettable because no Treaty represents better the core idea of (neo)functionalist reasoning: close co-operation in specific economic sectors is the key to overcoming national sovereignty and achieving European unity.2 But while the EU today is a true success story of economic integration, its inception was about peace and security rather than economic wealth. In other words, initial attempts of European integration after the Second World War started in the area of ‘high politics’. Once the negotiations on the Council of Europe had dwarfed federalist hopes for a United States of Europe, efforts to eliminate the risk of war in Europe embarked on a less glamorous path shaped by the plan of Robert Schuman and Jean Monnet to place the coal and steel production of France and Germany in particular under the common control of a supranational authority. The failure to establish a European political community, that would have united the ECSC with a newly founded European defence community in the early 1950s, made once again clear that successful integration would have to follow a functionalist rather than federalist logic. The focus shifted to the low politics of economic integration paving the way for the European Atomic Energy Community and the European Economic Community established by the Treaty of Rome in 1957. Throughout the following five decades, the European Community subsequently managed to expand its tasks culminating in the creation of an economic and monetary union by the Treaty of Maastricht in 1992. Political integration, by contrast, has seriously lagged behind. This is particularly true for foreign and security policy, but also parts of other policy areas, as we will see below.

The literature has developed different ways to map the task expansion of the EU. Some studies draw on Lindberg and Scheingold’s definition of integration in terms of scope and locus (level) of decision-making (Lindberg and Scheingold 1970: 67–71). While scope relates to the initial expansion of EU authority to new policy areas, locus stresses ‘the relative importance of Community decision-making processes as compared with national processes’ (1970: 68). As a measurement, Lindberg and Scheingold take the level at which decisions are formally taken. Others, by contrast, have focused on policy outputs at the EU level as measured in legislation (Directives, Regulations) and/or budgetary expenditures (Pollack 1994, 2000; Wessels 1997; Fligstein and McNichol 2001). Sometimes, the two measurements tend to become blurred when the level of decision-making is not only determined by the allocation of competencies in the Treaties but by the extent to which supranational institutions make use of their competencies (e.g. Schmitter 1996).3 While it may be interesting to look at legal output, it is not the best indicator for task expansion. First, the numbers of legal acts adopted by the EU do not say anything about their substantive content and relevance. Second, many Directives and Regulations expire after a number of years and are no longer in force.4 Third, in order to assess the relative weight of EU legislation, we would have to compare the legal output of the EU with those of its member states. Finally, legal output is strongly influenced by the institutions in which legal acts are adopted. Owing to unanimous decision-making, there were some noticeable exceptions to the core of the Common Market, such as transport and energy, where hardly any policy decisions had been taken at the EU level till the 1990s (Schmitter 1996: 124). If institutions have a strong impact on policy output, for the latter of which reliable data are hardly available, the former provides a better indicator for the task expansion of the EU.

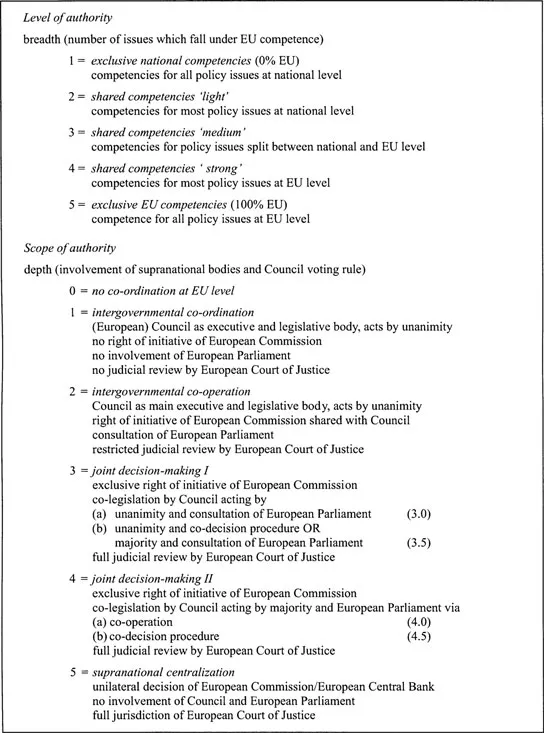

Given the various measurement problems, I suggest focusing on formal decision rules rather than legal output or expert estimates to trace the task expansion of the EU. The following analysis draws on the formal allocation of competencies and the institutional decision-making procedures as they evolved in the various treaty reforms. Following Lindberg and Scheingold, the level (breadth) of integration refers to the locus where the competence for policy decisions resides. It is operationalized by the number of issues in a given policy sector for which the EU has the power to legislate. Unlike Lindberg and Scheingold, the scope (depth) of integration is not understood as the initial expansion of EU tasks into new issue areas. This aspect is already covered by measuring the level of integration every time treaty revisions formally changed the allocation of competencies between the EU and its member states (principle of conferral).5 Rather, scope is operationalized by the procedures according to which policy decisions are taken focusing on the involvement of supranational bodies and Council voting rules (Figure 1). This conceptualization of scope borrows heavily from Fritz Scharpf’s work on institutional decision rules and modes of governance in the EU (Scharpf 2001, 2003).6

Figure 1 Mapping the task expansion of the EU

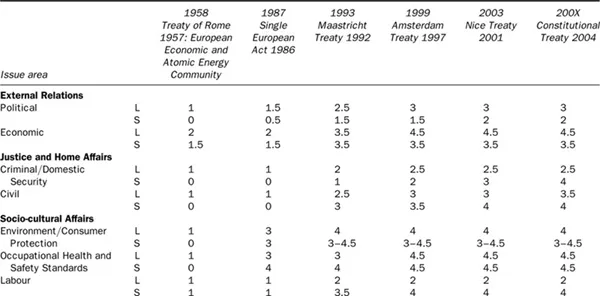

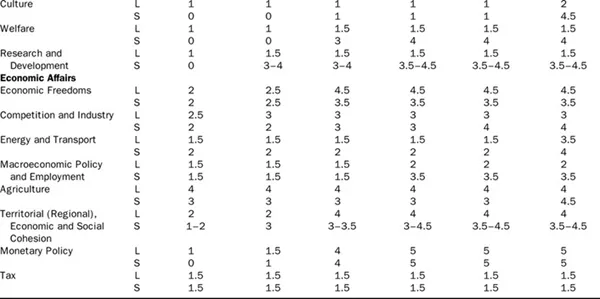

For each of the two dimensions, a five-point scale is applied. In order to come to a more differentiated assessment, the scale also allows for half points. Table 1 lists the scores for level and scope individually.

Table 1 Scope and level of European integration

Mapping the task expansion of the EU runs the risk of becoming an ‘impressionist exercise’ (Hix 2004: 18). In order to ensure some ‘inter-coder reliability’, I based my analysis on the reading of the Treaties rather than using secondary literature or expert assessments. Another problem in analysing the task expansion of the EU is the changing definition of issue areas both in the literature and in the Treaties. The list of policy fields as they are presented in Table 1 follows the analysis of Simon Hix (Hix 2004).

My overall findings do not seriously contradict those of similar studies (Hix 2004; Hooghe and Marks 2001; Donohue and Pollack 2001; Schmidt 1999; Schmitter 1996; Lindberg and Scheingold 1970). Yet, distinguishing between scope and level allows us to refine the puzzle of the disparity of regional integration and challenges at least partly the ways in which the literature has portrayed the EU’s task expansion. Drawing on Lowi’s distinction between regulatory, distributive, and redistributive policies many studies come to rather similar accounts (e.g. Pollack 1994: 108–13; Hix 2004: 8).

In the 1950s, the overwhelming majority of competencies still resided at the national level, while the EU held some responsibilities for market making (old regulatory) policies in order to dismantle national barriers to the free movement of goods and services, including competition and industry. In the 1960s and 1970s, however, the EU increasingly employed its market making powers to extend its competencies into the realm of market correcting (new regulatory) policies. Since national standards on environment, consumer protection, industrial health and security, or labour markets often work as non-tariff barriers to trade, the need for harmonization at the EU level became increasingly evident. A dynamic interpretation of the Treaties – particularly of Art. 28 (ex-Art. 30 ECT) which prohibits quantitative restrictions on imports and all measures having equal effect – and the use of Art. 94 (ex-Art 100 ECT) which allows for the harmonization of national regulations that directly affect the establishment or functioning of the Common Market allowed the EU to incrementally expand its task into issue areas that the Treaty of Rome had not defined as Community competence at all (e.g. Pollack 1994: 122–31; cf. Stone Sweet and Sandholtz 1997). The Single European Act (SEA) in 1986 codified this incremental process of ‘creeping competencies’ (Pollack 1994) and established what has become the ‘constitutional settlement’ of the EU (Hix 2004: 19). Subsequent treaty reforms in Maastricht, Amsterdam, Nice, and the Constitutional Convention consolidated the allocation of competencies laid out in the SEA: the EU holds exclusive competencies for market making (old regulatory) policies (including external trade) to ensure the free movement of goods, services, persons, and capital. It shares with the member states responsibilities for market correcting (new regulatory) policies that involve the harmonization of national standards on environment, consumer protection, industrial health and security, labour markets, etc. The member states collectively co-ordinate at the EU level their competencies for macroeconomic policies, justice and home affairs, and foreign and security policy. Finally, they remain by and large exclusively responsible for redistributive policy, including taxation and expenditure with some constraints agreed upon at the EU level.

Yet, a closer look reveals some important deviations from the neat picture that seems to portray the EU as a ‘regulatory state’ (Majone 1994). First, EU policy-making is not confined to regulation. True, the EU’s redistributive capacity is small compared to its members with their well-entrenched welfare states. It is currently limited to 1.27 per cent of the gross domestic product (GDP) generated by all member states (de facto, however, it lies at only 1.09 per cent). To put these figures into context, a spending power comparable to the German federation, for example, would correspond to a share of about 20 per cent of European GDP (cf. Börzel and Hösli 2003). Nevertheless, the EU transfers significant resources through its budget, including the common agricultural policy (CAP), regional policy, cohesion policy, and research and development policy. The CAP constitutes more than 60 per cent of the EU budget, and the structural and cohesion funds amount to 5 per cent of the GPD of some member states (Hix 1998: 42).

Second, market making and market correcting policies of the EU constrain the capacity of the member states for redistribution (Scharpf 1996, 1997). Next to state aid, competition rules, and the dynamics of regulatory competition according to which high labour costs may become a serious competitive disadvantage, the convergence criteria and the Growth and Stability Pact have put further constraints on the expenditure policies of the member states. This has created some pressure for what Haas would call a functional spillover from regulatory into redistributive issue areas. While the economic and monetary union (EMU) curbs the capacity of the member states for national macroeconomic stabilization, the EU as a whole does not possess these instruments. Asymmetric ‘shocks’ occurring in one part of the EMU, which might, for example, sharply increase unemployment in some EU member states, are difficult to address by the collective strategies of the centralized institutions (e.g. the European Central Bank (ECB)). Interest rates are now determined collectively for all EU states participating in EMU. The EU may face difficulties in achieving economic efficiency as long as national business cycles in the EMU area are not yet developing in a harmonized way (cf. Börzel and Hösli 2003). While the member states seek to retain exclusive competencies in areas of taxation and expenditure, they have intensified their attempts to co-ordinate their macroeconomic policies at the EU level (Luxembourg, Cardiff, Cologne processes). Moreover, as long as their domestic constituencies have a strong preference for maintaining the high level of social regulation and societal redistribution that characterizes the European (continental) welfare state, member state governments have strong incentives to harmonize national standards at the EU level in order to avoid competitive disadvantages to their domestic industries. Thus, for example, both the French and the German governments have repeatedly called for a certain degree of European tax harmonization in order to avoid ‘ta...