![]()

1 The history of processing speed and its relationship to intelligence

Amanda R. O’Brien David S. Tulsky

A review of recent theories of intelligence and research strongly supports the clinical utility of measuring processing speed (PS) in assessments of intelligence. However, the recent enthusiasm about processing speed as a significant component of intelligence is not an innovative idea in psychology. On the contrary, the use of processing speed as a major factor of intelligence and individual abilities lies at the very core of the birth of psychology as a quantitative science. During the late 1800s and early 1900s Wilhelm Wundt, Sir Francis Galton, James McKeen Cattell and other prominent psychologists strongly asserted that measures of sensory processes (e.g., processing speed) were at the heart of individuals’ intellectual abilities. The field followed suit and the Zeitgeist of science during the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century included the belief that anthropometric testing was the best way to measure an individual’s ability, resulting in the meteoric rise of processing speed research in intelligence.

However, after the early 1900s, the notion that speed was a central component to intelligence testing had waned, only to be “rediscovered” more recently as a valuable aspect of cognitive and neuropsychological testing (e.g., Donders, Tulsky, & Zhu, 2001; Martin, Donders, & Thompson. 2000). Today, researchers assert that processing speed measures within intelligence tests are among the most sensitive indicators of “acquired cerebral dysfunction,” (Hawkins, 1998). Although it is controversial, the debate over how such a “simple” factor as processing speed may contribute to higher cognitive functions has resurfaced in psychological theory. The drive to further delineate the concept of processing speed is currently a major focus of research and is discussed throughout the chapter.

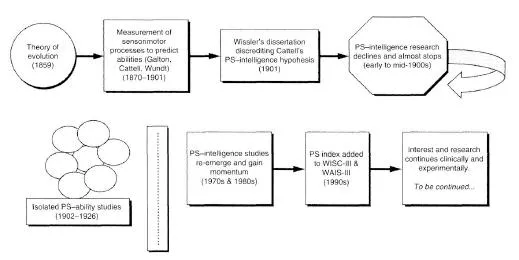

The goal of this chapter is to balance the recent “rise” in the assessment of processing speed by providing the historical context of examining processing speed as a component of intelligence and cognitive ability in both clinical and research settings. Therefore, the chapter provides an historical overview of processing speed beginning with the work of Galton and ending with current research. Various methodologies used to measure and study processing speed in the experimental realm are explained. The chapter also reviews more recent history that includes the story of how processing speed was brought back into the clinical realm through the Wechsler tests (see Figure 1.1). Further analysis of what processing speed can tell us about intelligence for healthy and clinical populations is discussed. The concept of processing speed as a simple versus complex cognitive construct is evaluated, including an argument for the need for a measure of more complex processing speed. Finally, recommendations for the future directions of the study of processing speed in the field of intelligence are articulated.

The history of processing speed

The birth of psychology as a science was largely composed of research on individual differences studied by measuring reaction time. Psychology’s focus on the study of individual differences in intellectual abilities occurred in the middle to late nineteenth century, partially due to the study of evolution. Darwin’s theories that behavioral and mental abilities could be inherited and that variation in these abilities (and subsequent hereditary “selection” of such abilities) naturally occurred had a major impact on scientific thinking. Although psychology had grown out of the field of philosophy, Darwin’s theories impacted on major thinkers in psychology and brought the study of individual differences and a more scientific approach to the field of psychology. Sir Francis Galton was a halfcousin of Darwin and was particularly influenced by his theories and his systematic approach to data collection and classification as evidenced in his 1869 book. Hereditary Genius (e.g., Clayes, 2001; Seligman, 2002).

Galton’s “anthroprometric” lab in London and Wilhelm Wundt’s first-ever psychological lab in Germany conducted the earliest research into individual differences by studying reaction time using various techniques. The initiation of research in these labs formed the foundation for formal

Figure 1.1 Overview timeline of the history of processing speed in the study and measurement of intelligence.

psychometric science and was the beginning of a prolific period of research in individual differences and intelligence testing. Galton is thought to be one of the first people to assert that mental processes (e.g., intelligence) could be quantitatively measured. Galton created a series of “psychometric experiments,” which the general public was introduced to and could experience first hand at the International Exhibition in London in 1884. He believed that these tasks, which measured various sensory and motor processes (of which reaction time was a major focus), reflected people’s intellectual strengths and weaknesses (e.g., Diamond, 1977). The popularity of Gallon’s work helped to generate a period referred to as the era of “brass instruments,” named as such for labs with numerous apparatuses that could be adapted with various brass fittings for measuring sensory processes (e.g., speed) that he believed were at the heart of individual differences in ability. During this period, the systematic study of mostly sensorimotor abilities, including reaction time, was widely accepted as a measure of mental variables.

The instruments used in the late nineteenth century to measure individual differences are interesting contributors to the story of assessment and intelligence. As stated by Michael Sokal (Sokal, Davis, & Merzbach. 1976). “such instruments show just what was new about the ‘new psychology’ that led its adherents to claim it as a distinct science (p. 59). Until Wundt began studying reaction time, the discipline of psychology had strongly asserted that the mental world could not be quantified or recorded. To attempt to do so was revolutionary, and not always well accepted by the establishment. One of the most ”famous“ instruments of the brass instruments era that was used to measure reaction time was the Hipp chronoscope, which essentially functioned as a very early type of stopwatch for psychological studies (see Figure 1.2). The Hipp chronoscope was quite complex, as shown by the following description:

A chronoscope driven by Clock-work, whose movement is regulated by a vibrating tongue: it is provided with two dials of 100 divisions each, one recording seconds and l0ths, the other l00ths and l000ths (sigma); the movement of the pointers is started and stopped by means of a clutch actuated by electromagnets, and there are connections whereby the record may either be started by making the circuit and stopped by breaking it, or vice versa.

(Warren. 1934)

Although the chronoscope allowed for breakthroughs in measurements of human reaction time, the many complexities of its design led to numerous problems of calibration and inaccuracies of measurement. To correct these problems, the machine required frequent recalibration and additional pieces were often added to the machine to attempt to control for errors, making the Hipp chronometer controversial for its shortcomings and especially the variability of its measurements (http://www.chss.montclair.edu/sychology/museum/mrt.html.; Sokal et al., 1976).

Figure 1.2 Hipp chronoscope. Photo used with permission from Dr. Thomas Perera and the Museum of the History of Reaction Time, Montclair State University, New Jersey: http://www.chss.montelair.edu/psychology/museum/mrt.html.

Another primary figure in the study of processing speed and intelligence was James McKeen Cattell; one of the great proponents of measurement of individual differences and use of “brass instruments.” Cattell came from a privileged background, and his scientific and professional interests, as well as a colorful and reportedly cantankerous personality, were part of a serendipitous mixture that put measuring individual differences and processing speed on the scientific map, particularly in the U.S. After graduating college in 1880, Cattell won a fellowship to Johns Hopkins University where he conducted experiments and argued about the importance of quantitative measurement of basic human abilities (e.g., reaction time) to study individual differences. However, he lost a second year of the fellowship to John Dewey, reportedly due to ongoing arguments with his supervisor, G. Stanley Hall and Johns Hopkins’ administration (Ross, 1972). Cattell therefore went to Europe in 1883 and worked with Wilhelm Wundt in the world’s first psychological laboratory, a decision that would have a major impact on American psychology and the field of psychological testing as a whole (Sokal, 1980). Cattell was struck by the scientific measurement and statistical analysis of human behaviors and individual differences that Wundt studied. After receiving his Ph.D. from Leipzig in 1886, Cattell continued his research under the direction of Sir Francis Galton in London, England. Galton, a pioneer in quantitative measurement of mental processes, had been measuring reaction time to study individual differences (Diamond, 1977). Cattell (1911) was heavily influenced by Galton’s mentorship, theories, and research and was quoted as saying that Galton was the “greatest man [he] ever knew” (Diamond, 1977, p. 48; Sokal, 1987. p. 27).

As Cattell started his professional career at the University of Pennsylvania, he continued to be heavily influenced by Galton’s work. Cattell became absorbed in the study of individual differences (see Sokal, 1987) and in 1890, he published a seminal article in Mind on the topic. He began the article by asserting:

Psychology cannot attain the certainty and exactness of the physical sciences, unless it rests on a foundation of experiment and measurement. A step in this direction could be made by applying a series of mental tests and measurements to a large number of individuals.

(Cattell, 1890, p. 373)

Cattell is credited with coining the term “mental tests,” which were tests used to predict or measure “intelligence,” although this construct was defined in various ways. Cattell’s 10 “mental tasks” measured reaction time and sensory sensitivity across domains, and included tasks such as “rate of movement,” “pressure causing pain.” “reaction time for sound,” and “number of letters remembered on once hearing,” using several instruments (e.g., brass instruments) discussed earlier (Cattell, 1890). His focus on reaction time demonstrates that processing speed was a key interest for Cattell.

In the 1880s and 1890s, the cultural and scientific Zeitgeist provided a very welcome reception to Cattell’s mental tests and his scientific study of individual differences. New York in the 1880s was an epicenter of scientific, cultural and artistic cooperation and productivity. As a result, universities in the city were thriving as well (Sokal, 1994). This inquisitive and open environment was in place when Cattell became a professor at Columbia in 1891. Cattell was even able to negotiate the assessment of every incoming student at Columbia College and the Columbia of Mines with his series of mental tests (Sokal, 1987).

Cattell’s powerful professional positions and his work at Columbia were major factors in explaining why the study of individual differences and processing speed thrived in the late 1800s and very early 1900s. More specifically, his anthropometric laboratory was productive and highly regarded, he started the journal Psychological Review in 1894, took over as editor of Science in 1894, and helped to establish, and later became President of the American Psychological Association in 1895.

Under Cattell’s presidency, the American Psychological Association (APA) created a committee on the potential collaboration between laboratories who were collecting measurements on mental and physical characteristics. The committee consisted of Cattell, Joseph Jastrow, Edmund Sanford. James Mark Baldwin, and Lightner Witmer (a student of both Cattell and Wundt). All but one of the committee members advocated Cattell’s methodology for testing individual differences and the APA recommended Cattell’s anthropometric testing as the preferred methodology for studying individual differences. Only Baldwin dissented, stating that there was a need for tests that measured more complex mental processes, giving the first public criticism of the “anthropometric tests” (Sokal, 1987). Shortly thereafter, Stella Emily Sharp, a graduate student of Edward Titchener, published her dissertation in which she criticized mental testing and individual psychology. She felt that Cattell’s measures of individual differences lacked any theoretical structure or useful application to functioning, which she supported with testing she had done on other graduate students (Sokal, 1987). However, these were the only two public criticisms of Cattell’s methodology during a time in which he had a great deal of power in the world of psychology.

Powerful scientists’ enthusiasm for measuring processing speed to determine individual differences, in the absence of clear hypothesis-driven research or sound research methodologies, continued to propel the topic, perhaps above and beyond what the evidence should have allowed. These researchers believed that the measurement of sensory processes, mainly differences in speed, would revolutionize assessment and psychology as a whole. Without any specific hypotheses about the mechanism(s) behind a relationship between speed and intelligence, these researchers still boldly asserted that their measures of processing speed could predict how successful people could be (although “success” was not specifically defined).

Research on speed and intelligence disappears

Several events in the late 1800s and very early 1900s effectively led to the significant decline of anthropometric testing and therefore to the end of the enthusiasm for measuring speed as a correlate of intellectual abilities. First, Edward Wheeler Scripture, a former student of Wundt’s, had been part of the core group of psychologists using anthropometric measures in psychology. However, similar to Cattell, he reportedly had a difficult personality and was involved in many arguments and conflicts with his colleagues. As a result, he spent much of this time in the 1890s struggling to keep his job and not on testing (Sokal, 1987). At the same time, Jastrow had been struggling to publish the results of his own testing and had run into a great deal of adversity, which reportedly led to a nervous breakdown in the mid-1890s. As a result, he was no longer part of this scientific movement (Sokal, 1987). This left Witmer as one of the last “heavy hitters” in anthropometric testing, who. at the time, was switching his focus to much more specific applications of testing in clinical psychology. Additionally, as interested in individual differences as Cattell was, he openly declared th...