This is a test

- 380 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Brief Therapy Approaches to Treating Anxiety and Depression

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Maintaining that most cases of anxiety and depression will respond to intelligently planned brief, directive therapies, Dr. Yapko has assembled this collection of 17 insightful and challenging papers illuminating such brief therapy methods. These innovative essays from such respected practitioners as S.G. Gilligan, J.C. Mills, E.L. Rossi, M.E. Seligman, and others, cover such topics as disturbances of temporal orientation as a feature of depression; the use of multisensory metaphors in the treatment of children's fears and depression; a hypnotherapeutic approach to panic disorder, anxiety as a function of depression; and more.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Brief Therapy Approaches to Treating Anxiety and Depression by Michael D. Yapko in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychologie & Geschichte & Theorie in der Psychologie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

SECTION TWO

Interventions for Depression

Chapter 2

Consciousness, Emotional Complexes, and the Mind-Gene Connection

Ernest L. Rossi, Ph.D., is a clinical psychologist who has authored, coauthor ed, and edited 14 books in the area of psychology. He is the editor of The Collected Papers of Milton H. Erickson on Hypnosis, and is currently the editor of the journal Psychological Perspectives. His most recent book, coauthored with David Cheek, M.D., is Mind-Body Therapy: Ideodynamic Healing in Hypnosis (New York: W. W. Norton, 1988).

It has been almost five years since the author first proposed the “mind-gene connection” at the Second International Ericksonian Congress in 1983 (Rossi, 1985). What was an emotionally intuitive notion at that time is rapidly becoming a reality today. One can hardly pick up a newspaper or magazine without reading about yet another breakthrough in molecular biology, genetics and their relationship to many forms of intellectual (e.g., Huntington’s, Alzheimer’s disease), emotional (e.g., manic-depressive), and psychosomatic problems. For those of us who have been out of school for more than a few years, this new research appears to be beyond any background we were offered; it involves an entirely new order of information and understanding.

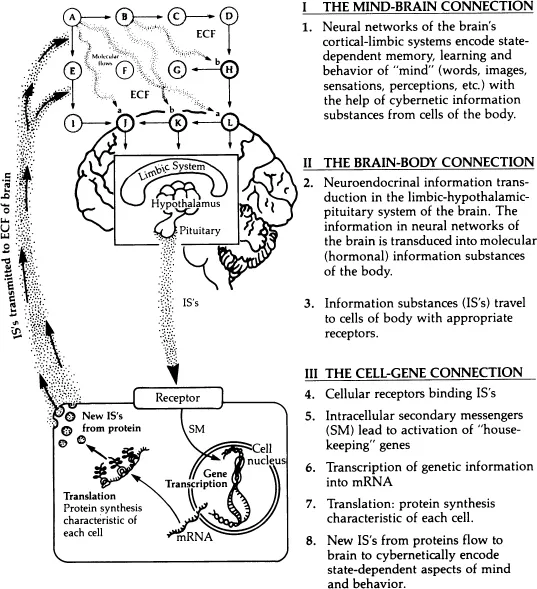

A basic difficulty in grasping this new order of information is its vast scope; it requires at least a general familiarity with the fundamentals of genetics and molecular biology, the neurobiology of memory and learning, and 100 years of clinical and phenomenological research in hypnosis, psychoanalysis, and psychosomatic medicine. Is there any common concept that can unite these apparently diverse levels of understanding? A number of researchers over the past few decades believe there is; they believe it is the concept of information and, in particular, the process of information transduction (Delbruck, 1970; Rossi, 1986b [Part II]; Weiner, 1977). Information transduction refers to the process by which information is changed from one form into another. In this chapter, we will explore what is known about three stages of the process in mind-body information transduction: (1) how sensory-perceptual, emotional, and cognitive information on the phenomenological level of mind is transduced into the neural information of the brain; (2) how neural information of the brain is transduced into the molecular information of the body; (3) how molecular information of the body accesses our genome and transduces genetic information back into the neural information of the brain and the phenomenological experience of mind.

Most readers will recognize that this three-stage outline is essentially a cybernetic loop of communication or information transduction between mind and body on a molecular level. In order to understand this process of communication, we need some background in the new theory of information substances and their receptors in emotions and mind-body healing.

INFORMATION SUBSTANCES AND THEIR RECEPTORS IN MIND-BODY COMMUNICATION

For over 100 years it had been an article of faith in the field of pharmacology that drugs evoked their physiological responses by first binding to hypothesized receptors on the cell walls of the nerves and tissues of the body. Finally, in the 1970s, a series of investigators demonstrated the physical reality of the insulin receptor (Cuatrecasas, 1971), the opiate receptor (Goldstein, Lowney, & Pal, 1972; Pert, 1976; Pert & Snyder, 1973a, b), and the peptide molecules that bind to these receptors (Hughes, 1975). The revolutionary significance of these discoveries was in the recognition of a new principle in molecular biology, endocrinology, and psychopharmacology: Peptides and their receptors are a general class of messengers in biological systems that mediate intercellular communication at the molecular level. This conception was recently expanded upon by Schmitt (1984). He introduced the term “informational substances” to designate all of the newly discovered types of “messenger molecules” and their receptors that modulate brain, body, and behavior. It is interesting to note that Schmitt, who has long been regarded as the founder of modern molecular neuoroscience, now finds that an essentially mentalistic concept such as “informational substance” is necessary to understand the biological dynamics of what were previously called “neuroactive substances.”

Within this new category of informational substances, Schmitt included the following: classical neurotransmitters (acetylcholine, dopamine, epinephrine, serotonin, etc.); steroid hormones (estrogens, androgens, glucocorticoids, etc.); peptide hormones (all the hypothalamic, pituitary, and endocrine hormones, such as ACTH, B-endorphin, luteinizing hormone, thyroid, insulin); and the neuropeptides (substance P, the angiotensins, bradykinin, cholecystokinin, vasointestinal peptides, etc.). He also included growth factors (such as nerve growth factors and epidermal growth factors), instructive factors that are involved in gene expression, and certain proteins, such as messenger RNA and glycoproteins, that are involved in memory and learning. The common denominator of these information substances is that they all trigger receptor proteins located on either the cell walls, the cytosol within the cells, or the genes themselves within the nucleus of the cell. Once triggered, these receptor proteins initiate the cascade of metabolic processes that account for the special characteristics of each cell, tissue, and organ of the body.

Information substances and their receptors thus integrate all the major homeostatic and regulatory systems of mind, brain, and body that were previously thought to function in an autonomous manner: The peripheral and autonomic nervous systems, the endocrine system, and the immune system are now known to modulate each other’s actions on the molecular level. Because many of these molecules can play overlapping roles as neurotransmitters, neuromodulators, growth factors, and the like, the more generic term of information substances is now needed to cover their multiple communication functions throughout the mind-brain-body (Iversen, 1984; Nieuwenhuys, 1985; Pert, Ruff, Weber, & Herkenham, 1985; Ruff, Pert, Weber, Wahl, Wahl, & Paul, 1985a; Ruff, Wahl, Mergenhagan, & Pert, 1985b; Ruff, Farrar, & Pert, 1986).

A second major point made by Schmitt is that many information substances modulate neural activity by triggering receptors that are located on many parts of the nerve cell rather than only at the synaptic junctions portrayed by conventional neurology. He summarized this new principle of parasynaptic information transduction as follows (Schmitt, 1986, p. 240):

(1) | Neurons may chemically intercommunicate by the mediation not only of the dozen-odd classical neurotransmitters but also by peptides, hormones, “factors,” other specific proteins, and by other kinds of informational substances (ISs), a term that seemed more generally applicable than “neuroactive substances” that was previously used. |

(2) | Alongside of, and in parallel with, synaptically linked, “hardwired” neuronal circuitry, that forms the basis for conventional neurophysiology and neuroanatomy, and that operates through conventional synaptic junctions, there is a system that I call “parasynaptic.” In parasynaptic neuronal systems, ISs may be released at points, frequently relatively remote from target cells, which they reach by diffusion through the extracellular fluid. Such a system has all the specificity and selectivity characteristics of the conventional synaptic mode; in the parasynaptic case, the receptors that provide the specificity and selectivity are on the surface of the cells where they can be contacted by, and bind to, the IS ligands diffusing in the extracellular fluid. |

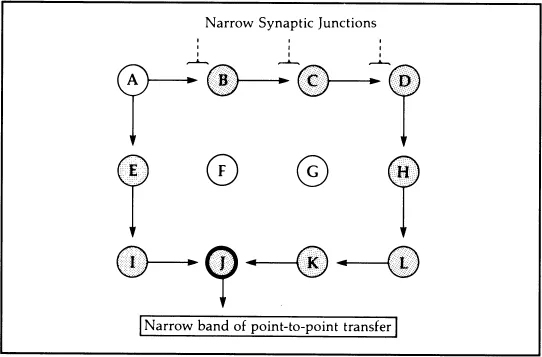

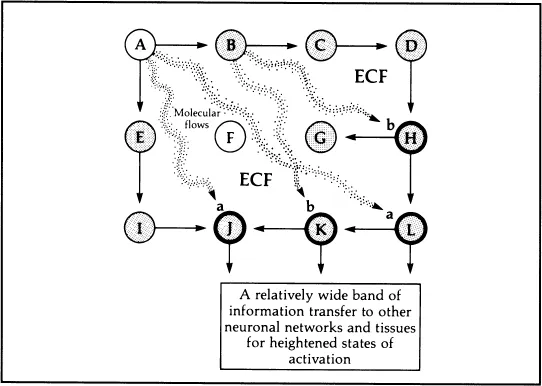

The “hardwired” neuronal circuitry is fairly fixed in its anatomical structure; it does not change its characteristics easily but it is very rapid in its speed of information transmission (on the order of milliseconds). The IS-receptor system “software,” by contrast, is in an ongoing process of flexible change, but it is slower in its rate of information transmission. Figure 1 illustrates the earlier classical view of a neural network where communication is mediated in a relatively narrow band of linear information flow between one neuron and the next by the classical neurotransmitters. Figure 2 illustrates how these classical neurotransmitters are now known to be supplemented by information substances of the parasynaptic system that flow through the extracellular fluid (ECF) in a broader, nonlinear pattern.

Figure 1

Figure 2

The author has described in detail how these information substances that are contained and transmitted throughout the ECF of the brain can serve as the molecular mechanism for encoding and transducing the flow of the information between the phenomenology of mind and the neural structure of the brain. There is now clear experimental evidence in animals (goldfish), for example, that the diffusion of information substances (glycoproteins) between brain cells is responsible for encoding memory, learning, and behavior (Shashoua, 1981). The rate of release of these information substances into the extracellular fluid is increased during intensive learning experiences. This training results in long-term memory and learning that is abolished when the information substances are removed from the extracellular fluid by administration of antisera that block the ISs’ ability to bind to neural receptors. This means that memory and learning are states dependent upon the presence or absence of these information substances that encode experience in the neuronal networks of the brain. There is a vast body of historical and contemporary experimental and clinical research that supports the hypothesis that many forms of memory and learning can now be conceptualized as either overtly or covertly state-dependent (Rossi, 1986b; Rossi & Ryan, 1986). This suggests that our currently developing conceptions of the modulation of the entire mind-brain-body by IS-receptor communication systems will enable us to devise new types of experimental studies of the relationships between behavior, genes, and molecules. Schmitt noted the relationships that require more study when he wrote (1984, p. 994):

The brain contains all the types of steroid hormones.… As ISs, they exert a duplex action: (1) a relatively fast (minutes) direct action on synaptic properties, regulating impulse traffic in particular neuronal nets, and (2) a slow (hours) indirect effect involving specific gene activation leading to the synthesis of essential proteins, e.g., specific receptors. Steroid hormones regulate behavioral patterns involved in reproduction, territorial defense, mood and other affective states [McEwen, 1981; McEwen et al., 1982]. For present purposes, the steroid hormones illustrate the integrative control of both the fast bioelectrical events involving the passage of impulses through neuronal nets (i.e., the neurophysiological processes that underlie specific behavior patterns), and the slow gene-activated processes that lead to the synthesis of proteinaceous material which, like specific receptors, form the molecular substratum of behavioral patterns.

The implication of this passage is that the entire class of information substances and their receptors may be important modulators of the fundamental mechanism of memory, learning, emotion, and behavior on the molecular level.

EMOTION, MOTIVATION, AND PSYCHOSOMATIC MEDICINE

Theories of emotion, motivation, and psychosomatic medicine have tended to merge with one another as we have learned more about their biological basis. For example, during the past 50 years a series of investigators has established through the methodologies of neuroanatomy (Livingston & Hornykiewicz, 1978; Maclean, 1970; Papez, 1937), neuroendrocrinology (Scharrer & Scharrer, 1940), electrophysiol-ogy (Nuwer & Pribram, 1979), and psychophysiology (Mishkin & Petrie, 1984; Olds, 1977) that the limbic-hypothalamic system of the brain is the locus for the generation and modulation of many of the classical phenomena of emotion, motivation, and psychosomatic medicine. More recent studies find that the IS-receptor systems of the brain also have their highest levels of concentration in the limbic-hypothalamic system (Nieuwenhuys, 1985; Pert et al., 1985). This is the basic type of prima facie evidence that implicates IS-receptor systems in the generation and modulation of emotion and motivation on the molecular level. Pert (1986, 1987) generalized this research into a new theory of the molecular basis of psychosomatic medicine.

An overview of the entire process of information transduction on the molecular level from mind to gene is presented in Figure 3. The three-stage outline of cybernetic communication between mind and body alluded to earlier is clearly evident in Figure 3 as (1) the mind-brain connection, (2) the brain-body connection, and (3) the cell-gene connection that produces and releases information substances back into the bloodstream where they can modulate many other body processes, as well as the manifestation of mind (memory, learning, imagery, emotion, and behavior) when they reach the neuronal networks of the brain.

By far the most difficult to understand of these three stages of mind-body communication is the mind-brain connection. There may be a couple of reasons for this: We are all rather vague about what we mean by “mind”; our scientific-materialistic-deterministic world view since the time of Descartes has led us to believe that mind and body are two separate realms that may or may not interact. Because of these philosophical difficulties it might be wise, for now, to acknowledge that the scope of this resolution of the “mind-body problem” presented in this paper is restricted to the practical interests of the therapist in mind-body healing. It is important for scientific researchers and clinicians to have a theoretical model of how mind and body communicate in health and disease so they can test the new hypothesis generated by the model. In a recent volume on the theory, practice, and research of mind-body healing, Rossi and Cheek (1988) outlined 64 such research projects in order to assess the validity and parameters of the general model illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3

CONSCIOUSNESS AND PSYCHOLOGICAL COMPLEXES

The general model of mind-body communication presented in Figure 3 may still seem so remote from the daily concerns of the practical psychotherapist as to be almost worthless. Let us, therefore, turn to at least one area where we already have enough information about the model to illustrate its potential usefulness for a new psychotherapy of the future. Figure 4 illustrates how the general model might be applied to the relationships between information substances and the state-dependent encoding of consciousness, emotional states, and psychological complexes. Although Figure 4 applies primarily to women, analogous processes are currently under study in men (Rossi & Cheek, 1988).

A glance at the chart of a woman’s continually changing concentration levels in the blood of the four major hormones regulating menstruation and ovulation (progesterone, estrogen, luteinizing hormone, and follicle-stimulating hormone) in the shaded portion of Figure 4 illustrates the psychobiological basis of the mood and mentation movements that modulate the normal rhythms of feminine consciousness. These four major hormones are in turn controlled by neuroendocrinal protohormones and hormones of the limbic-hypothalamic-pituitary system. Many of these hormones have been implicated as the types of information substances that modulate state-dependent memory, mood, and learning.

Depth psychologists, such as C. G. Jung, have long recognized the rhythmic or “wave like” biological basis of “psychological complexes” and emotional life in general. In his essay “A Review of the Complex Theory,” Jung wrote (1960b, pp. 96–98):

What then, scientifically speaking, is a “feeling-tone complex”? It is the image of a certain psychic situation which is strongly accentuated emotionally and is, moreover, incompatible with the habitual attitude of consciousness. This image has a powerful inner coherence, ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Conference Overview and Objectives

- Acknowledgments

- About The Milton H. Erickson Institute of San Diego

- Conference Faculty and Presentation Titles

- SECTION ONE Keynote Address

- SECTION TWO Interventions for Depression

- SECTION THREE Interventions for Anxiety

- SECTION FOUR Therapeutic Approaches for Anxiety and Depression

- Name Index

- Subject Index