This is a test

- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Adolphe Appia swept away the foundations of traditional theatre and set the agenda for the development of theatrical practice this century. In Adolphe Appia: Texts on Theatre, Richard Beacham brings together for the first time selections from all his major writings. The publication of these essays, many of which have long been unavailable in English, represents a significant addition to our understanding of the development of theatrical art. It will be an invaluable sourcebook for theatre students and welcomed as an important contribution to the literature of the modern stage.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Adolphe Appia by Richard C. Beacham in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Performing Arts. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The reformation of theatrical production

Introduction

The challenge of staging the works of Richard Wagner provided Appia with his first and most fundamental task, one leading ultimately to the provision of a completely new approach to theatrical art. Preoccupied to the point of obsession with the problem of adequately realizing Wagner’s works in the theatre, Appia spent the last decade of the nineteenth century focusing all his creative resources and mental energy on its solution. This achievement was prodigious and, eventually, its effect upon contemporary staging – indeed upon the very concept of the theatre – was revolutionary. Within a period of fewer than ten years, Appia articulated theories and expressed them in designs that swept away the foundations that had supported European theatre practice since the Renaissance. In their place he laid down what became the conceptual and practical basis for theatrical art for many years to come. As Lee Simonson wrote, Appia’s theories

elucidated the basic aesthetic principles of modern stage design, analysed its fundamental technical problems, outlined their solution, and formed a charter of freedom under which scene designers still practice . . . The light in Appia’s first drawings, if one compares them to the designs that had preceded his, seem the night and morning of a First Day.

(Simonson 1932: 352, 359)

Appia’s passionate critique of traditional stagecraft was soon taken up by others, some of whom conceived similar although less comprehensive ideas independently of him. Before long, the ‘new art of the theatre’ was being promulgated everywhere, often by people with little direct knowledge of Appia or of his decisive contribution to the movement which they so ardently promoted. But it was Appia alone who in the 1890s, with extraordinary clarity of vision, first provided a complete assessment of the disastrous state of theatrical art, and who, with quite astonishing foresight, first suggested the solutions which in time, and frequently at the hands of others, laid down a new foundation for the modern theatre.

Richard Wagner succeeded in his later operas in creating a new art form – a union of drama and music – which overturned the conventional concept of opera and, in time, that of theatre in general. Having joined within himself the roles of composer and dramatist, he achieved a remarkable creative breakthrough, fashioning a new type of musical drama in which a work’s inner values as expressed through the music were conjoined with its outward meaning as articulated through dialogue and plot. The new medium thus achieved could become, as Wagner both practised and prophesied, a uniquely expressive art form.

He recognized, moreover, that if the autonomous artist, the composer-dramatist, were to present his work successfully before an audience, it would be essential for him to master and, ideally, control all the disparate elements of production. Since his operas were simultaneously music and drama, the latter not fixed for performance by a score, their integrity could be maintained only through rigorous attention to all the details of theatrical production.

Yet despite drastic and far-reaching reforms, in the end Wagner himself failed to carry through any genuine revolution in staging. To be sure, his purpose-built theatre, the Festspielhaus at Bayreuth, completed in 1876, was highly innovative. Its semicircular amphitheatre, modelled on ancient example, in theory allowed every spectator an equally good and unimpeded view of the performance. From it he banished the customary distinctions of social hierarchy, as well as all the elaborate décor and ornament – anything that could draw attention away from the stage itself. For the first time the auditorium was darkened during performance, and even the orchestra was hidden from view to allow the spectators to observe the world of the opera without distraction.

On stage, however, the situation was different. Wagner spared no expense or effort in equipping his theatre with the most advanced technology of the period, but it was all essentially in the service of the traditional aesthetic of scenic illusion. It is difficult to assess the extent to which Wagner himself was aware or troubled by the incompatibility between his works and their realization on stage. Whether consciously or not, by placing his performers within a relentlessly illusionistic scenic environment where little or nothing was left to the imagination, he ensured that, visually, the settings could never express the inner spiritual world suggested by the music. Although his librettos abound with precise stage directions and scenic descriptions, Wagner was generally less than satisfied with the results and seems to have desired more than he could visualize – something at any rate other than the romantic naturalism which his craftsmen invariably produced. At the end of his life he lamented that ‘in this field of musical dramaturgy, alas, all is still so new and hidden in the dust of bad routine’ (Roth 1980: 155).

Appia first saw Wagner’s own last production, that of Parsifal in 1882; and later attended Cosima Wagner’s faithful restagings of Tristan and Isolde and The Mastersingers in 1888. In Dresden he witnessed a production of the Ring. He was overwhelmed by the impact of these works as music, while goaded by the unshakeable conviction that their potential as pieces for the theatre, and as the basis for an entirely new form of theatrical art, had been left unexplored and unexploited, and, moreover, had been all but totally obscured under the gross burden of contemporary stage practice. Here, at last, in Wagner, Appia recognized an artist whose titanic genius might redeem theatre and raise it to the level of true art. Here were sublime works whose full power and beauty could only emerge, be revealed and realized, could only exist in the theatre itself – but only if a theatre could first be fashioned to contain them.

As Appia recorded later in the autobiographical essay ‘Theatrical experiences and personal investigations’, he began his work by first trying to understand and explain Wagner’s fundamental failure himself to develop an appropriate means of staging his own works; a failure that had resulted in a style of production which, with all its inadequacies, became enshrined as orthodox after his death. With the help of his friend, Houston Stewart Chamberlain (who later married Wagner’s daughter, Eva), Appia was able to spend time at Bayreuth, observing and analysing both the productions themselves and the technical intricacies of the Festspielhaus. He acquired a direct and concrete understanding that challenged him at the time to develop his own theory further and later ensured that the theory when it emerged was firmly grounded in sound technical expertise and practical knowledge.

The expressiveness of Wagner’s operas resides in the music and the dramatic actions generated by the music and libretto on stage. To attempt at the same time to give that music a completely realistic materialization was not only impossible, but, inevitably, it buried and obscured from the audience the essential qualities of the work. It was this perception that gave rise to the first series of scenic reforms formulated by Appia in the 1890s, which were outlined in the introductory section of this book. His study of Wagner’s operas formed the critical core of his work for many years to come, with subsequent investigations, practical experiments and theoretical essays all radiating outward from the mass of these explosive ideas.

Wagner’s composition as a work of art was conditioned by an overall unity of conception, and in performance this conception – the meaning of the work – was bodied forth on stage. Any genuinely artistic staging must therefore also exhibit a unity of expression which would be the sum of its parts: each scene, each event on stage, each setting must be carefully balanced and coordinated with the others to contribute its appropriate measure to the overall quality of the production. To do this, Appia formulated his concepst of a hierarchy of production through which all the expressive elements – scenic space and objects, light, movement and gestures of the performers, all conditioned by and subject to the demands of the musical score – would be integrated and harmonized.

His first extended essay, written in 1891–2 but never published in his lifetime, was ‘Comments on the staging of the Ring of the Nibelungs’ (‘Notes de mise en scène pour L’Anneau de Nibelungen’). In a concise and straightforward format, Appia discusses, essentially through concrete description, the problems that Wagner’s work presents and his own solutions to them, solutions that required comprehensive reform of contemporary stagecraft, although not as yet of its technical resources. His second essay, published as a small book in 1895, was Staging Wagnerian Drama (La Mise en scène du drame wagnérien). This was a more theoretical rendering of the earlier work, presented now in the context of a totally new analysis of the principles governing the relationship between music, stage actions and setting. Finally, in 1895 Appia began to write his major work, Music and the Art of the Theatre (La Musique et la mise en scène), which both summarized and revised his two earlier essays, moving beyond Wagner altogether to describe the implications of his theories generally for a radical and fundamental reformation (amounting virtually to a rebirth) of theatrical art. It was published in German in 1899 as Die Musik und die Inscenierung.

Figure 2 Appia c. age twenty.

The writings through which Appia first expressed his observations and ideas reflect the intensity of his passion, and sometimes also the struggle he had in trying to capture logically and coherently – to wrestle into language – perceptions and concepts which first came to him only visually and emotionally. One must bear in mind Appia’s own description of the process: how he first contemplated and reacted to Wagner’s works by striving imaginatively to give them their appropriate (and somehow inevitable) theatrical realization, and only later attempted to extrapolate from the results of this process a conceptually unified aesthetic theory. It is not, therefore, surprising that his writing is sometimes convoluted or vague, and occasionally repetitious and overwrought. He is, after all, attempting to use language to map out an altogether unfamiliar mental landscape. But when in retrospect one reviews and responds to the overall pattern of his work, in a sense retracing to its core the process out of which Appia himself first formulated his theory, one is startled finally by the intensity, the genius and the beauty of the original vision. One is also struck palpably by the realization that to review and summarize the concepts generated from within that vision is to compile a concise compendium of the first principles of the modern theatre, for as Lee Simonson described Music and the Art of the Theatre, ‘the first one hundred and twenty pages are nothing less than a textbook of modern stagecraft’ (Simonson 1932: 354).

Theatrical Experiences and Personal Investigations

(1921) [Excerpts]

Volbach, pp. 47–721; Bablet, 4, pp. 36–56

The way in which an author expresses his dramatic intentions must be perceived through the technical aspects of his text. What the performers must say or sing is less important than how they present it to the audience. If the author limits himself to the spoken word, the technical scope is also restricted. If, on the other hand, he deems a musical element to be necessary for his communication, there is virtually total freedom in delivering the words. Between the two extremes – a recitation in which music is subordinated to speech for the sake of purely spoken expression, as opposed to a performance of those passages in which music alone is the revealing element – every nuance is possible, and staging must be adapted to them.

The imagination of the author or the director, although stimulated by the verbal text, should not be the source of scenic conception; that must always and entirely derive from the nature of the poetic-musical text. Music determines modifications in time duration and, through that, in the space . . .

I directed all my efforts in order to liberate the actor. I was very much aware of this principle; only the manner of its application and the results were not yet clear to me, although they were starting to develop.2

I therefore approached the mise en scène of the Ring with the single desire of being true to my own vision . . . After many years of experience, or rather years of noting them in what was necessarily an unorganized fashion, I began to practise an altogether unknown art, for which neither my environment nor my memory could provide any guidance, and for which all the elements had not yet been discovered or analysed. Nevertheless, I was convinced that in following my own vision, I would discover the truth . . .

Deep in my heart and before making any designs, I knew that for me production means the performer. I therefore took the score of [Wagner’s opera] Rhinegold and analysed the opening scene entirely from this point of view. I will attempt to give the reader some sense of my approach. First of all I try to isolate the episodes of the action to determine their precise character, bearing in mind the elements that bind them together rather as a mason does with his mortar . . . Another invaluable judgement involves the theatrical significance of the episodes ... A still more important one is . . . the role each episode plays in the inner drama, i.e. its significance for the universal meaning transcending visible action and casual appearance . . .

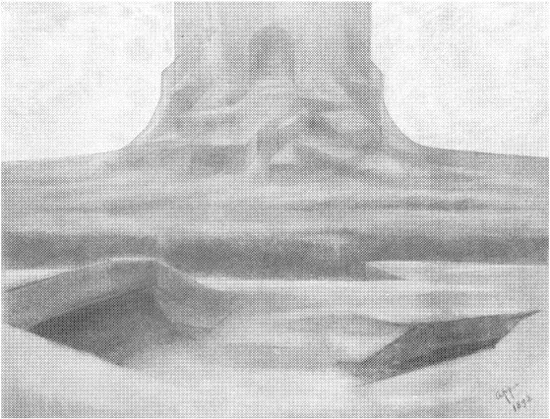

Figure 3 Appia’s 1892 design for a unit setting of the Valhalla landscape of Rhinegold.

With the essential facts in mind, we can then begin to design the setting, while remembering that the second factor, theatrical significance, is determined by what we have provided for the performer . . . Everyone will agree that an interesting flower arrangement requires more flowers than in the end are actually used. It is the same with the mise en scène, and therefore I prepare various drawings depicting interchangeable and suggestive locales, rather like a word puzzle when not all the letters provided are necessary to compose a specific word . . . It involves an element of guesswork, surely, and this in turn demands some general sense of form. It requires too a faith in the unconscious which, oddly enough, has never misled me. One might go further and arrange all these tentative settings within a general framework suggested by the place of action without strict regard for the hierarchy [of production elements]. It then becomes an approximate unit setting that can be changed as desired until it finally suits each episode. It is at this point that the mortar – the binding elements – comes into play . . .

Imagine all the elements involved in this work: text, music, external dramatic design (plot), the hidden reality of the inner drama, peculiarities and social status of the characters, their actions and reactions, the manner of their delivery, the areas assigned to them, organic relationships, lighting with all its variations, shades, shadows, colour. All of these to be managed within the range of technical feasibility and all made to converge at a single moment, the time of performance! No single method could accomplish this; the field is too vast and complex to mould into a single frame . . .

The question may now be put whether unity is desirable at all for staging; whether the director cannot use various devices within the same work, even though the score ought to suggest only a single mode for achieving the style that captures the poetic image of the music? Perhaps we ought to put the question differently: i.e., ‘What is the nature of unity of production?’ In fact this is how the problem should be formulated in order to reveal the principle that determines everything else.

For the poet-musician, unity lies in the dramatic intention that inspired a specific work, and only that work . . . The source of one of Wagner’s scores is forever inaccessible to us. Our knowledge of it begins with the technical application of such elements of expression as the score conveys. Because these elements are subordinate, the unity they display does not originate with them. I...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- Preface

- Introduction: Adolphe Appia, 1862–1928

- Part I The reformation of theatrical production

- Introduction

- Theatrical Experiences and Personal Investigations (1921) [Excerpts]

- Music and the Art of the Theatre (1899) [Excerpts]

- Ideas on a Reform of Our Mise en Scène (1902)

- Part II Writings on eurhythmics

- Introduction

- Theatrical Experiences and Personal Investigations (1921) [Excerpts]

- Return to Music (1906)

- Style and Solidarity (1909)

- The Origin and Beginnings of Eurhythmics (1911)

- Eurhythmics and the Theatre (1911)

- Eurhythmics and Light (1912)

- Concerning the Costume for Eurhythmics (1912)

- Part III Essays on the art of the theatre

- Introduction

- Actor, Space, Light, Painting (1919)

- Art is an Attitude (1920)

- Living Art or Dead Nature? (1921)

- Theatrical Production and its Prospects for the Future (1921)

- Monumentality (1922)

- The Art of the Living Theatre (A Lecture for Zurich) (1925)

- Part IV Aesthetic and prophetic writings

- Introduction

- Theatrical Experiences and Personal Investigations (1921) [Excerpts]

- The Work of Living Art (1919) [Excerpts]

- The Gesture of Art (1921)

- Picturesqueness (1922)

- Mechanization (1922)

- The Former Attitude (1921)

- Appendix: Appia’s Commentary and Scenario for The Valkyrie, Act III (1892)

- Notes

- Select Bibliography

- Index