This is a test

- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Adopting an interdisciplinary approach, this book investigates the style, or 'voice, ' of English language translations of twentieth-century Latin American writing, including fiction, political speeches, and film. Existing models of stylistic analysis, supported at times by computer-assisted analysis, are developed to examine a range of works and writers, selected for their literary, cultural, and ideological importance. The style of the different translators is subjected to a close linguistic investigation within their cultural and ideological framework.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Style and Ideology in Translation by Jeremy Munday in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Discursive Presence, Voice, and Style in Translation

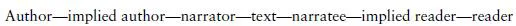

The first important theoretical question is how the role of the translator relates to that of the author since the presence of the translator upsets the narratological representation of the narrative process commonly depicted as in Figure 1.1 (following Chatman 1978; Rimmon-Kenan 2002):

Fig. 1.1. Common narratological representation of the narrative process

‘Author’ here is the biographical author; ‘implied author,’ a concept introduced by Booth (1961) for the image of the author and his or her beliefs built by the reader from reading the narrative. The ‘narrator’ is the ‘teller of the tale,’ sometimes addressed to a specific narratee in the text. The ‘implied reader’ (Iser 1974) is the counterpart of the implied author, namely the image of the reader or readership constructed by author or the real reader from reading the text. Finally, the text is, one hopes, indeed read by a real reader. However, as Schiavi (1996) and Hermans (1996a) point out in a pair of important themed papers published in Target in 1996, narratology tends to treat original texts and translations identically in the type of schema illustrated in Figure 1.1 above. Schiavi (1996: 14) proposes a modification to take into account the role of translation which completely alters the second half of Figure 1.2:

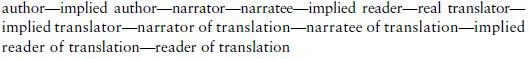

Fig. 1.2. Narratological representation of translation

In this Figure, the first translation component is the ‘real translator,’ who is associated with the ‘implied reader’ of the ST because he or she is “aware of the kind of implied reader presupposed by a given narrative” (ibid: 14); that is, the translator will be aware of the possible or likely audience of the text and will be able to compensate (or otherwise) for any lacunae in their sociocultural knowledge of the source language or culture. This awareness is expressed in the linguistic choices made in the translated text. Schiavi’s justification for the subsequent inclusion of an ‘implied translator’ follows that for the implied author above:

A translator will in fact build a set of translational presuppositions according to the book to be translated and the audience envisaged. It is also a useful concept for all those that are made by putting together bits and pieces of existing translations of the same book; in that case there may not be a translator’s name on the cover, but there certainly is a ‘translation intent,’ obeying given norms and producing a new text. (Schiavi 1996: 15)

The evident mediating role of the translator and the effect this may have on style will be discussed further below, but for the moment let us consider the complexity of Schiavi’s diagram. It may be true that the concept of an implied author can be used to explain the fact that the beliefs expressed in a novel may not be those of the biographical author; it may also be true that the theoretical concept of the ‘implied translator’ may usefully reflect that a TT is the outcome of collaborative work of translator, copy editor, and editor and may cover those cases of multiple or anonymous translations or indeed retranslations where the work of an earlier translator informs the new TT.1 Nevertheless, Schiavi’s schema is not necessarily of enormous benefit in understanding what goes on in the translation process. A first step towards clarification would be to produce two parallel narratological lines linked by the identification of the real translator as a real reader of the ST who interprets presuppositions concerning the implied reader of the ST (Figure 1.3):

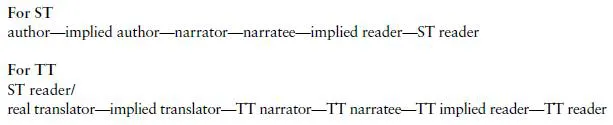

Fig. 1.3. Parallel narratological lines of translation

As well as identifying the real translator with a real ST reader,2 the parallelism of the diagram also emphasizes the links (1) between the implied author (of the ST) and implied translator (of the TT) and also (2) between the author (of the ST) and the translator (of the TT). That is, in the process of creating the TT the implied translator and translator to some extent take over the role of the ST implied author and ST author. One consequence, in Schiavi’s words, is that

a reader of translation will receive a sort of split message coming from two different addressers, both original although in two different senses: one originating from the author which is elaborated and mediated by the translator, and one (the language of the translation itself) originating directly from the translator (Schiavi 1996: 14).

This is critical for the interpretation of the linguistic analysis of style as well as for any suggestion of manipulation and distortion in translation: the translated text is a mix of source and target, an amalgam of author and translator, a ST mosaic overlaid with TT tesserae that is the result of the translator’s conscious and unconscious decision-making. Whereas, for many reviewers and readers, the TT mosaic is the ST and the translator merely a layer of transparent varnish, the difficulty for translational stylistics is in determining the pieces that are characteristic of the style of the particular translator and those that are visible signs from the ST underneath. This “split message” is directly related to the question of authority over the text. Although the words of the ST are a basic constraint against which the TT choices may be measured, the translator may deliberately choose to subvert them or may unconsciously distort them by patterns of low-level lexical choices. At the very least, the message coming from the translation is relayed in a different code that bears the translator’s print.

That Schiavi, despite the complexity of her schema, focuses above all on the author and translator (as both reader and mediator/re-writer) suggests that these are indeed core roles in the actual translation process. This is borne out by the approach adopted by Michael Toolan, in his Narrative: A Critical Linguistic Introduction, which treats the author and narrator as core participants in the production of (ST) narrative, and the reader as the core participant in the reception (Toolan 2001: 67). Similarly, Rachel May in her book The Translator in the Text, a study of Russian literature translated in English, uses the terms ‘author in the text’ and ‘reader in the text’ in place of ‘implied author’ and ‘implied reader’ because her concern “is less with actual or potential readers than with the various ways the reader and author may be encoded within the text and, above all, with the way the translator alters the codes” (May 1994: 167, note 2). Even though we choose not to adopt May’s terms, her assertion about the shifting power relations within ST and TT does chime with our main focus. For May:

[t]he evidence suggests that translators traditionally engage in rivalries not only with editors and authors but with the voices in the text, particularly with the voice of the narrator. [... ] The translators are subtly altering all the power relations in and around the text—between character and narrator as well as between author and text or text and reader. (May 1994: 115)

The translator, or implied translator if we consider others involved in the production of the TT (such as the publisher, editor, and copy-editor), is in a powerful position. He or she may deliberately re-mould the TT to fit a pre-existing personal or public ideological framework or narrative (Baker 2006); alternatively, the more subtle and even unconscious stylistic rewordings which occur in any text have the potential, because they come from a different code and different writer, to alter the voices of the ST author and narrator, as noted by May above. No TT narrative can ever be a true calque of the ST. Just as there may be reliable or unreliable narrators, so may there also be reliable and unreliable translators. An unreliable translator may deliberately manipulate the message; even reliable translators alter stylistically because of their mere presence. This is not ‘betraying,’ in the image of the aphorism traditore tradutore, but creating something new with a subtly distinct voice. Our interest is in what traces and voices these translators insert in the text.

In narratology, ‘voice’ normally refers to the narrative voice (RimmonKenan 2002: 87–106); “who speaks?” in Genette’s terms); in other words, it relates to the author’s voice(s) or presence as perceived through the act of narration (Booth 1961: 18). This may manifest itself in many different forms: direct authorial address to the reader, comments from supposedly ‘reliable’ narrators, a shift of point of view and character within the narrative, alteration of ‘natural’ sequence or duration and even the very choice of material and the decision to write (ibid.: 16–20). “In short, the author’s judgement is always present, always evident to anyone who knows how to look for it” (ibid.: 20). If the author’s judgement is always present, then in translation so is the translator’s. That is a crucial starting point of this volume.

There are three elements of narrative fiction that are commonly presented in contemporary narratology: the ‘story’ (i.e., the basic events and characters), the ‘text’ (the way these events are presented, ordered, and focused) and the ‘narration’ (the levels and ‘voices’).3 Although authorial judgement may affect all three elements, it is only the text that is immediately visible (Rimmon-Kenan 2002). Therefore, any construction or reconstruction of narrative and authorial voice needs to be primarily based on an analysis of the text, on the linguistic choices visible to us. In a descriptive translation analysis, this means a comparison of both ST and TT. For Booth, following Sartre, the author’s voice is a “manipulating presence” (Booth 1961: 19), introducing evaluation at all levels. In translation, this finds its counterpart in the translator’s “discursive presence” (Hermans 1996a) or “mediating presence” (Malmkjaer 2004). Such a presence may be evident, in the case of translator footnotes and prefaces, but most commonly it will be realized in the words of the translated text that, by many, will be read in isolation and judged as the unmediated words of the ST author. Any alteration, muffling, exaggeration, blurring, or other distortion of authorial voice will remain hidden until and unless some element of the TT reveals the mediation or until the TT is compared to its ST. To use Hermans’s words, the authorial voice needs to be “confronted” with “the translator’s voice, as an index of the translator’s discursive presence” (Hermans 1996a: 27). Hermans contends that “a ‘second’ voice” is always present in translated discourse and that this may be manifested in one of three ways:

- 1. by displacement caused by the specific historical or ‘cultural embedding’ of the original text. When translated for a new readership, this requires the adaptation or even introduction of cultural allusions. Nevertheless, inevitably the trace of the ST implied reader is not totally erased;

- 2. by ‘self-referentiality,’ where the form of the language of the ST is emphasized with word-plays or even specific commentary. Hermans (ibid.: 29–30) gives the example of Descartes’ Discours de la méthode, discussed by Derrida (1991), where the French ST declares it is written in French not Latin. This sentence is omitted in the Latin translation but in English becomes an obvious marker of translation through its contradiction: “And if I write in French... rather than Latin... it is because...” (Descartes 1968: 91, cited in Hermans 1996a: 30);

- 3. by ‘contextual overdetermination,’ where the context and form of the ST do not allow for translation. Hermans gives the case of the initials of a character in a Dutch novel 4 which spell out the first letters of a well-known and relevant Dutch proverb and are dealt with in a translator’s footnote.

These are perhaps points at which the translator’s voice becomes loudest, where the translator is most ‘visible’ (Venuti 1995) even without comparison with the ST; other points are paratexts, material outside of the text, such as a critical introduction, evaluative footnotes, book cover, and the like (Genette 1997), which Baker (2006) describes as framing the narrative of translation. Other phenomena which show the translator’s presence are omissions (the silencing of the ST author can speak volumes), rewriting, or summarizing, the latter only ascertained by comparing the TT to the ST. We shall see examples of all these strategies in the following chapters. However, the most interesting, because it is the most subtle and least immediately visible, are shifts in linguistic style. Hermans implies this when he stresses the need for “a model of translated narrative which accounts for the way in which the translator’s voice insinuates itself into the discourse and adjusts to the displacement which translation brings about” (1996a: 43). The choice of the verb ‘insinuates’ hints at the concealment of the act.5 In a recent study entitled “Hearing Voices: James Joyce, Narrative Voice and Minority Translation,” Carmen Millán-Varela (2004) tries to build on the work of Hermans and Schiavi by investigating the translator’s voice in the Galician translation of James Joyce’s short story “The Dead.” One finding of interest is that of “a hidden mediating presence,” that of a Spanish TT, a translation by the Cuban Guillermo Cabrera Infante, which seems to have provided a syntactic and lexical model for the Galician TT (ibid.: 47). Other changes to the narrative voice involve the omission of certain reporting clauses (turning direct speech into free indirect speech) and of evaluative adverbs (the equivalents of ‘surely,’ ‘literally’). Millán-Varela feels that the narrator’s voice is thereby “suppressed” (ibid.: 50). Nevertheless, although she contends (ibid.: 52) that “the linguistic and stylistic study of translated texts can provide crucial information about the agents involved, their ideology and motivations,” it is not carried through in her paper. Indeed, a problem facing any such paper is that of how to generalize from a particular case study. The advantage of studies such as May’s, and our own, is that many related case studies can be brought together, confronted, and consolidated in a bid to advance the study of style and of descriptive translation studies in general. Logical starting points are the study of translations linked by time, place, translator, or literary movement, conforming to some of the subcategory restrictions of descriptive studies indicated by Toury (1995: 10) in his extension of Holmes’s famous mapping of translation studies (Holmes 1988). In the case of the present book, that will be (mainly) translations of Latin American writing in English in the second part of the twentieth century.

The concept of voice itself is ideological since the possibility of a consistent voice presupposes a single unified self, which has been challenged by postmodernism and most notably in the work of Mikhail Bakhtin (1981). Bakhtin’s view of narrative as polyphonic (multi-voiced), dialogic (orientated towards a response, mixing characters and styles), and founded in the variety of heteroglossia,6 removes the absolute boundaries between both source and target and between the intraand extralinguistic features of the text. Bakhtin thus links voice, style, and discourse in the dialogic intermeshing of characters, groups, and points of view. This has profound implications for our analysis of style with its contingent influences of ideology and narrative point of view and its impact for the identity of the text, translator, and author. Bakhtin’s ideas indeed underpin May’s analysis of English translations of major Russian writers. May’s contention is that:

translators incline, by and large, to replace the inner dialogism of a text with discrete voices, and the heteroglossia “from below” with greater literariness “from above.” [... ] Even more significantly, translation changes the author’s own relation to the novel. Whereas Bakhtin describes the author as interacting with the play of voices in the text, sculpting from the raw material of “someone else’s speech,” for the translator the entire work is someone else’s speech into which all its once-alien voices are subsumed. All too often this means that the translator redefines the work from above, asserting boundaries between voices and replacing a fluid narrating voice with one more authoritative. It would seem that the translator, having less “authorship” over the text, asserts more authority rather than playing with the boundaries of that authority. Words that were “half someone else’s” for the author are, for the translator, all someone else’s; in the process of taking control of them, the translator commonly re-evaluates them as all his or her own. (May 1994: 4–5)

The assertion that translators tend to separate out the voices in the text and impose a more literary norm on the non-standard varieties in a text requires further investigation to see if this is always the case and what external constraining factors are at play. The questions of authority over the text and ownership of the words are also more problematic than May might suggest. The translator reworks the already sculpted material of the author’s words into new words in the target language which, as discussed above, may bear the fingerprint of the translator’s idiolect or preferred translation strategies. The translator certainly filters the voices and may alter them by doing so. Evaluation or re-evaluation takes place at points of ambiguity where interpretation is essential, but it is not uncommon in translation for the ST author’s lexis or syntax to show through, otherwise there would be no discussion of phenomena such as interference, one of Toury’s probabilistic ‘laws’ of translation (Toury 1995).

A further complicating factor is that literary translators themselves often use the concept of a unified (rather than polyphonic) authorial voice as a key guiding element for their work. ‘Voice’ is generally used in the singular, to reflect the consistent form of expression of an author and the aural value of the source words. Th...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Routledge studies in linguistics

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Author

- Acknowledgments

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 Discursive presence, voice, and style in translation

- 2 Ideological macro-context in the translation of Latin America

- 3 The classic translator pre-1960: Harriet de Onís

- 4 One author, many voices: The voice of García Márquez through his many translators

- 5 One translator, many authors: The “controlled schizophrenia” of Gregory Rabassa

- 6 Political ideology and translation

- 7 Style in audiovisual translation

- 8 Translation and identity

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index