![]()

Sport management and sport business: two sides of the same coin?

Hans Westerbeek

Institute of Sport, Exercise and Active Living, Victoria University, Melbourne, Australia and Free University of Brussels, Brussels, Belgium

The ambitious title that this special issue carries raises expectations about its contents. Sport business in a global context, and within that context the impact of commercial sport on communities … a whole range of potentially complex issues packaged into one title.

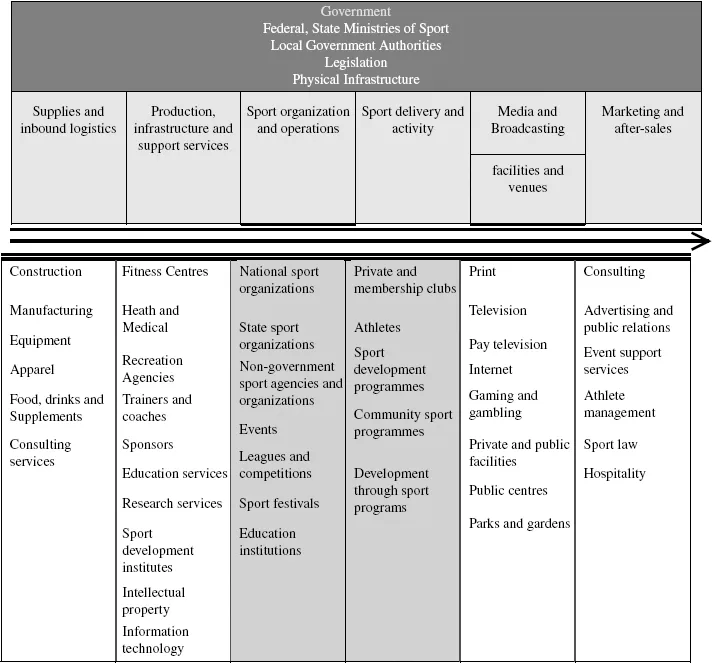

A special issue offers the opportunity to thematically focus, and to raise issues outside the mainstream of research in the discipline area. In this case, sport business implies commerce and trade in the sport industry, and how commerce and trade impact on communities – the latter ranging from groupings of sport participants and sport spectators to the array of stakeholders that have close or remote relations with sport and sport organizations. The net is purposely cast widely in this special issue with both global and local examples of (different types of) impact on a variety of ‘communities’. Rather than specifying types of communities – an intellectual effort that is required in future work but for which the collection of articles in this issue remains too diverse – ‘community’ in this special issue refers to ‘the people living in one particular area or people who are considered as a unit because of their common interests, social group or nationality’.1 Contributing author Raymond Boyle focuses on ‘hybrid communities of mediated sport fans’ and the impact new media is having on their congregation and consumption behaviour, whereas Shakya Mitra looks at a new community of (middle class Indian) sportfans and what has been the impact of the rapid rise to sport business success of the Indian Premier League cricket competition. Koji Kobayashi, John M. Amis, Richard Unwin and Richard Southall debate the impact of globalizing forces on the management behaviour of the senior corporate communities of two Japanese sporting-goods manufacturers. Corporate decision makers are not an end-user community, but an instrumental stakeholder in the value chain of sport nevertheless (see also Figure 1 later in this article). Ramon Spaaij and Hans Westerbeek propose a different approach to determining ‘impact’ through a typology of markets for social capital in the sport business environment. Although their discussion is limited to identifying marketplaces for ‘social capital’, their typology provides a starting point for describing different types of ‘end-user communities’, in this case communities that may benefit from different types of social capital. In a way, Fred Coalter precedes this line of thinking by questioning what may be the impact of sport-for-development programmes on local communities of socially and economically deprived citizens, how impact is measured, and what can and cannot be expected of such programmes. Marc Theeboom, Reinhard Haudenhuyse and Paul De Knop query how community sport programmes benefit socially deprived groups. Their focus is on questioning the positive impact that traditional (sport and government) organizations have, if they possess the best organizational purpose and structure for the effective delivery of these programmes. The authors also provide a potential alternative group of organizations for the delivery of community sport s in order to improve positive impact.

Reflecting on the work that has been submitted for this special issue, it made me more aware of the exponential journey that sport has travelled regarding academic programmes that have been established and research that has been conducted in the name of revealing the many unknowns in the sport industry. In order to talk about sport business we may briefly need to reflect on sport management, and how the professionalization of an industry has been fast-tracked by the onset of globalization, delivering an increasingly complex, dynamic and competitive arena of business. Sport management in that regard is about how to run sport, how to develop its management, how to improve its offering and output – a clear focus on the production of sport. Sport business on the other hand is about the wider perspective of industry, its marketplaces and the congregation of producers and consumers. It focuses on the commodification of sport, how to best commercialize potential products and how to sell them to a growing and progressively more segmented marketplace. This introductory article is about setting the scene for this special issue, in the process debating some conceptual and definitional confusion that may exist.

It all started with sport management?

Although universities in North America have delivered academic programmes in sport management and sport administration since the 1960s, the applied discipline of the management of sport organizations has only recently been embraced by (some) universities as a serious field of academic inquiry and teaching. A valid proxy for sport management’s academic ascendance may well be the establishment of regional associations of sport-management academics, the oldest being the North American Society for Sport Management (NASSM)2 founded in 1985. The establishment of NASSM was followed by the European Association for Sport Management (EASM, founded in 1993)3, the Sport Management Association of Australia and New Zealand (SMAANZ, founded in 1995)4 and the Asian Association for Sport Management (AASM, founded in 2002).5 Interestingly, the majority of early, established sport-management programmes did not emerge in faculties, schools or departments of management but, rather, were mostly created in academic environments of applied sport science such as kinesiology, exercise science, physical education and human movement sciences. It seems that disciplines closest to the organizational practice of what was predominantly volunteer-driven sport activity were also the first to detect (or even feel) the need for more professional sport management.

Fast-forward to 2010 when business schools seem to have discovered the inherent attractiveness of sport as a means to (cross) promote their programmes, coinciding with a significant demand for sport-industry-specific degree programmes. As a result they have incorporated professional and research sport-industry programmes into their offerings. Not only are universities competing with each other in regard to offering degrees in sport management, but internally there seems to be an arm-wrestle looming between the applied-sport disciplines and the business schools delivering management and marketing degrees, about who is best suited to deliver sport-management programmes. The applied sport scientists argue that they best know sport, which is countered by the business professors who argue that it is about management and marketing applied to sport organizations.

This friendly clash of mother disciplines of sport management – applied sport science and management/marketing – reflects the increasing complexity of the sport industry. Only a few decades ago the majority of organizational activity in sport was delivered through non-commercial, volunteer and community-based initiative. Today the sport-industry landscape is dramatically different. The majority of financial resources in sport are generated and spent by highly skilled and experienced professionals who are in the sport industry to make a living. The organizations that they run vehemently compete for limited resources and even when they are not-for-profit by nature, they still require a no-nonsense rational business approach to their management in order to survive and ultimately thrive. Not only has the increasing importance of this business approach to sport led to a partial shift of sport management educational programmes to be housed in business schools, it has also led to (re)defining the scope of the sport industry. As such it may extend the discipline domain of sport management as well. As foreshadowed in the title of this article, where sport management may have been focused on the production of sport, sport business extends this focus on exchange between producers and consumers in the sport industry as a whole. In the next section this wider industry perspective is visualized using a value-chain6 approach.

A value-chain approach to describing the sport industry

In a consulting report to the Australian Government’s Department of Culture, Information Technology and the Arts (DCITA), Westerbeek and Smith adapted Porter’s value-chain approach to describe the sport industry. An ‘industry’ can be defined as ‘the people and activities involved in producing a particular thing, or in providing a particular service’.7 A more elaborate definition states that industry is ‘a department or branch of a craft, art, business or manufacture: a division of productive or profit-making labour; especially one that employs a large personnel and capital; a group of productive or profit-making enterprises or organizations that have a similar technological structure of production and that produce or supply technically substitutable goods, services, or sources of income’. The last part of this definition is critical, in that the categorization of businesses under the banner of a single industry is largely dependent on the types of goods or services that they produce. More to the point, these goods and services need to satisfy similar needs and wants of consumers, and production of those goods and services take place along similar technological lines. Therefore, when attempting to define the ‘sport industry’, one describes and categorizes all suppliers of goods and services that satisfy (or indirectly contribute to satisfying) sport needs. The point in the context of this paper is that it dramatically increases the range of organizations that have an involvement in producing, delivering and selling sport, and as such require (at least some form of) sport management. Westerbeek and Smith8 propose the following sport-industry definition:

The sport industry encompasses all upstream and downstream value adding activities emanating from the delivery of sport products and services. A sport product or service occurs when a human-controlled, goal-directed, competitive activity requiring physical prowess (irrespective of competency) is delivered or facilitated.

Upstream value adding activities include sectors or organizations which provide supplies, infrastructure or support products or services to allow or facilitate the delivery of a sport product or service. Downstream value adding activities include sectors or organizations which provide distribution, marketing or customer relationship (after sales) products or services to a sport product or service.

Figure 1. A value-chain-based model of the sport industry including some product examples (adapted from Westerbeek and Smith, 2004).

They go on by developing a visual model of how a value-chain-based model may apply to the describing the sport industry. The simplified model that is presented in Figure 1 needs to be ‘read’ from left to right (from upstream ‘raw materials’ to downstream ‘end products’, and from ‘input’ to ‘throughput’ to ‘output’). The top layer of the model represents organizations and processes that impact all stages of value adding, either by providing financial or physical resources or how they influence the value-adding process through policy or legislation.

It is beyond the scope of this article to further elaborate on the specific contents of the sport-industry typology. As briefly outlined in the introductory paragraph of this article – because an intellectual effort is required to further specify types of communities in future work – Figure 1 may well serve as a starting point to describe all relevant stakeholder communities in the sport value chain, and also specify what the differential impact of their value-adding activities is. However, for this article it is sufficient to observe that the value-chain approach offers interesting opportunities to visualize the expanding scope of the sport industry and, as such, the extension of the domain of sport management. With the scope of the industry being about derived sport value, management of organizations in the industry can be referred to as sport management. In other words, where a few decades ago the focus of academic education and research would have been on the professionalization of sport organizations and its delivery management (the middle two columns in Figure 1), today this only represents a small part of creating and mining sport’s value. The expansion of the industry has led to a range of value-adding activities becoming sub-industries in their own right. It can indeed be argued that sport as an industry has grown up – that organizations9 and professions10 have matured and that volunteer-driven management has largely been replaced with managers educated to operate in the executive office.11 Beyond the process of professionalization and returning to the theme of this special issue, it can be observed that sport-management knowledge is required in unexpected market environments such as Third World countries, urban ghettos, multimedia company boardrooms and a range of government ministries that are not responsible for sport policy, but require sport’s value in their production process nevertheless.

Ergo, although the applied discipline of sport management possibly best describes the range of academic programmes that are offered it does not unite international perspectives on the diversifying nature and scope of sport products. It is a(n) (value-chain) industry perspective that better allows for a discussion about sport business in a global context.

So what is sport business?

We are forced to consider the answer to the above question in the context of globalization as it can be argued that driving forces of globalization, such as economic liberalization and technological progress, have been critical in sport becoming an arena of big business.12 The breakdown ...