![]()

A ‘Second Transition’ in Spain? Policy, Institutions and Interparty Politics under Zapatero (2004–8)

Bonnie N. Field

This work analyses whether the first government of Socialist Prime Minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero (2004–8) represents a ‘second transition’ in relation to the transition to democracy that occurred in Spain in the mid-1970s. After reviewing the concept of a second transition and the electoral context, the work analyses the patterns of change and continuity in the areas of public policy, political institutions and interparty politics. It concludes that while there were significant changes during the Zapatero government, they do not amount to a second transition.

In 2004, the Spanish parliamentary election came just a few days after the devastating Islamist terrorist attacks on Madrid commuter trains. The Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE, Spanish Socialist Party), with first-time candidate for prime minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, won an unexpected victory over the conservative Partido Popular (PP, Popular Party), newly led by Mariano Rajoy. The PSOE formed a minority government under Prime Minister Zapatero with the support of primarily leftist parties. This victory came on the heels of eight years of PP governments under José María Aznar. Spaniards went to the polls again in 2008, and returned a victory for the Socialists and Zapatero to government, though still without an absolute majority.

Few people prior to the 2004 elections would have imagined many of the developments that occurred between 2004 and 2008. Under Zapatero Spain rapidly withdrew Spanish troops from Iraq; held a very public, political debate on the Spanish Civil War (1936–39) and the Franco dictatorship (1939–75); passed very progressive social legislation, including gay marriage and adoption and a sweeping gender equality act; and expanded autonomy in six of Spain’s 17 regions. The press, politicians and academics have referred to some or all of these developments as a ‘second transition’ that alters or revisits policies, institutional arrangements and political strategies that were established during Spain’s transition to democracy in the mid-1970s.

Spain’s transition to democracy is widely understood as a consensual transition, though largely controlled by the outgoing regime. Reformists within the Francoist regime and later of the centrist party, Unión de Centro Democrático (UCD, Union of the Democratic Centre), and leaders of the opposition, including socialists, communists and some peripheral nationalists,1 engaged in multilateral negotiation and compromise that gave birth to the new Spanish democracy. These negotiations did not, however, occur in a vacuum, nor were all negotiating actors on an equal footing. The non-democratic regime was clearly in control of all of the political institutions prior to the elections of 1977, and during the constituent legislature (1977–79) the only democratically legitimate institutions were the parliament and the government. While many of the emblematic political institutions of the regime had been dismantled, such as the Francoist pseudo-party, el Movimiento, and the vertical unions, state institutions had not yet been reformed, including the military, police, courts and local governments. The intact military and security apparatus represented a potential veto player should the transition go too far or too quickly.

This environment surely contributed to the moderation of demands from the left and some peripheral nationalists. In this context, the negotiating parties agreed many of the hallmarks of the Spanish transition: an amnesty that included both regime supporters and opponents; the more tacit agreement to look forward instead of addressing Spain’s divisive past; the Moncloa pacts that confronted economic crisis through socioeconomic accords signed by the parliamentary parties; and the political institutions embodied in the constitution of 1978. The parties by and large avoided polarisation on historically divisive issues such as religion and the monarchy. In many ways it was a conservative transition; yet it would be incorrect to conclude that it was only the left and the peripheral nationalists that compromised.

Soon after Zapatero’s election in 2004, the Economist magazine published a survey article on Spain titled ‘The second transition’.2 The article praised many of the advances the country had made economically, culturally and politically since its transition to democracy. It also pointed out weaknesses, including the lack of independence of a range of institutions, such as think-tanks, the judiciary and the media, and the timidity and deference of Spanish business to the government. It also highlighted that Spain lagged in social areas, such as gay rights and the role of women, and the burgeoning challenges of immigration and regionalism. It also boldly claimed that the 2004 elections were likely to be seen ‘as the natural end of the first era of Spain’s post-Franco transition to democracy. What follows now is a second era—a transition from a simple democracy to a more complicated, more sophisticated one.’

The terminology of a ‘second transition’ is not simply a foreign one. In fact, PP leader and future prime minister Aznar wrote a book called España: la segunda transición (Spain: The Second Transition) in 1994, in which he discussed his ideas for the future of Spain, proposing an alternative to the Socialists who had been governing since 1982. Yet the terminology gained most traction amongst the left and Spain’s peripheral nationalists. Pasqual Maragall of the Partit dels Socialistes de Catalunya (PSC-PSOE, Socialist Party of Catalonia), then president of the Catalan regional government, and a variety of party leaders, including Carod Rovira of Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC, Republican Left of Catalonia), Artur Mas of Convergència Democràtica de Catalunya (CDC, Democratic Convergence of Catalonia), Josep Antoni Duran i Lleida of Unió Democràtica de Catalunya (UCD, Democratic Union of Catalonia) and Gaspar Llamazares of Izquierda Unida (IU, United Left), all referred to hoped-for territorial reforms, such as of the Spanish Senate, the recognition of the multinational nature of the Spanish state, the extension of regional governments’ competencies (stipulated in ‘statutes of autonomy’) and a revision of regional financing, as a second transition.3 In academic and policy circles, Zapatero’s governing agenda has also been dubbed a second transition (Druliolle 2008; Encarnación 2009; Mathieson 2007; Woodworth 2005), including the decision to recognise and address Spain’s divisive past, as well as Zapatero’s progressive legislative agenda that has sparked the ire of conservative forces, such as the Catholic Church and the PP. Aznar’s expression has therefore come back to haunt the PP, which denounces the so-called second transition. As reported in El Mundo,4 former PP interior minister Jaime Mayor Oreja stated that the party had to confront ‘what some have called the second transition’, and not ‘settle in it as if it were something inevitable’.

It is not only the potential reform of state institutions and Zapatero’s policy agenda that have led some to refer to this period as a second transition. It is also about the division, rancour and hostility that characterise interparty relations. Political commentator Paddy Woodworth (2005) wrote an article titled ‘Spain’s “second transition”: reforming zeal and dire omens’, in which he discusses Zapatero’s willingness to take bold action on major issues without consensus, the catch-word of the Spanish transition, with the PP and without concern for the ‘implicit and explicit limits that period [the transition] set on political change’. He also draws attention to the PP’s invective opposition. More ominously, he states, ‘There are abundant indications that a new seismic shift is underway, which may resolve some of the issues that remained outstanding after most Spaniards voted for a democratic constitution in 1978. This “second transition” could change the shape of the Spanish political landscape almost as dramatically as the first one did. The question is whether this upheaval will permit the creation of new and improved democratic institutions, or simply put the old ones under severe strain.’

The concept of a second transition is a tricky, multifaceted one. In one connotation, it clearly questions the manner in which the transition to democracy was carried out, the perceived limits that were placed on it and what the left and moderate nationalists gave up due to their willingness, or readiness, to compromise. It can also suggest a second stage of democratic deepening that expands political and social rights to previously excluded or underrepresented groups and improves some of the deficits of the current democracy. Yet, for others, a second transition means undermining a delicate consensus that permitted democracy to flourish in Spain, which can only serve to divide Spaniards and put at risk the unity of the Spanish state.

This issue provides the opportunity to systematically analyse some of these developments. Its goal is to provide insight into the patterns of continuity and change manifested during the first Zapatero government. This work first reviews the electoral and parliamentary context. It then presents an overview of the patterns of change and continuity in three admittedly overlapping areas: public policy, institutional reform and interparty relations. In all three areas, there were clearly significant departures, and Zapatero accomplished an impressive number of the PSOE’s manifesto promises, even though he led a minority government. Yet, the terminology of a second transition is likely overstated.

Competitive Electoral Politics and Minority Government

The 2004 elections took place in extraordinary circumstances, and delivered an upset victory to the Socialists. Yet the 2004 (and 2008) elections continued a pattern, established in 1993, of highly competitive national elections that produced minority governments. During this elections cycle, it is the 2000 election that produced a PP absolute majority that is anomalous (Oñate & Ocaña 2005). However, the relative importance of leftist and leftist-nationalist parties for the Zapatero minority government is a novel development (Field, this issue).

In 2004, voting took place just a few days after the horrific terrorist attacks on Madrid commuter trains that killed 192 people and injured scores more (Van Biezen 2005; Fishman 2007; Lago & Montero 2006; Powell 2004; Santamaría 2004; Torcal & Rico 2004). Prior to the attacks, most polls predicted a narrow victory for the governing PP. In the three days that transpired between the attacks and the elections, the PP government was increasingly criticised for its handling of information regarding the investigations into those responsible, and was accused of continuing, many claimed deliberately, to attribute the attacks to Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA, Basque Homeland and Freedom), the Basque-independence terrorist organisation, when evidence pointed to Islamists. The assumption was that it would be more electorally damaging to the incumbent PP government if the attacks were of Islamist origin, given that Prime Minister Aznar had supported the US-led Iraq War in the face of extremely widespread public opposition.

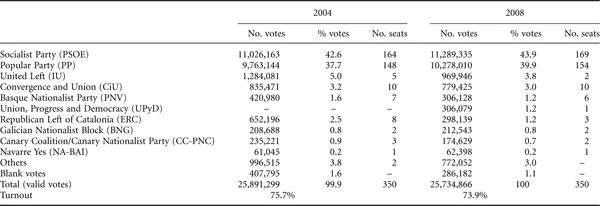

The elections swept the governing PP from office and dealt a defeat to Prime Minister Aznar’s hand-chosen successor, Mariano Rajoy. Most academic analyses conclude that the attacks had an impact on the voting behaviour of the Spanish electorate. Based on an analysis of survey data, Lago and Montero (2006, p. 26) conclude that the attacks impacted on behaviour in two ways: ‘first, because the government was blamed for the attacks as a result of its support for the war in Iraq; second, because of the view that government information about those responsible for the attacks was at best self-interested and at worst manipulative’. Most also argue that the effects of the attacks on voting cannot be considered in a vacuum, however. As Fishman (2007) argues, PP strategies and policies during the prior four years, such as the deteriorating relations between the PP government and multinational periphery, and the PP’s social and economic policies, also mattered. The evidence also indicates that it was increased turnout, new voters and the strategic voting of the supporters of smaller parties that delivered a victory to the PSOE and not a large swing away from the PP to the PSOE (Torcal & Rico 2004, p. 115). The results of the 2004 and 2008 elections are presented in Table 1.

Table 1 Election results, Congress of Deputies, Spain

While it was widely considered an unexpected victory for the Socialists, we cannot know for sure who would have won the 2004 elections had the attacks not occurred. Polls indicated that the difference between the PSOE and PP shrank as the campaign progressed. Also, in every policy area except economic and employment policy, the public viewed the PP’s governing performance negatively (Lago & Montero 2006, pp. 30–31), and the final tracking poll conducted a week prior to the election indicated that 59.3 per cent of respondents believed the country ‘needed a change of party in government’ (Fishman 2007, p. 272).

The Socialists had last governed from 1982 to 1996 under Prime Minister Felipe González, whose final years in office were riddled with corruption scandals. In winning the 2004 elections, the PSOE reversed a long pattern of electoral decline and ended the leadership crisis produced by González’s departure. Zapatero also represented an important generational passing of the baton from those who led the party during the transition to democracy to those, for the most part, who came of political age in the post-transition years. This is part of a larger generational change in the political parties; transition political leaders have largely left the front lines of politics (Field 2008).

In the PP’s view it would have won the 2004 elections had it not been for the terrorist bombings (Powell 2004, p. 379). It was also clear from the political climate of the following four years that the PP had tremendous difficulty accepting the PSOE’s victory. The extremely tense and divided political environment led Whitehead (2007, p. 19) to include Spain’s 2004 elections as an example of the challenges posed by ‘closely fought elections’, stating, ‘the political climate is as polarised and embittered as at any time since the death of long-time dictator Francisco Franco in 1975’.

After four years of government during which the divisions between the principal parties were made abundantly clear, Spaniards returned to the polls for parliamentary elections in March 2008 (Bosco 2009; Field 2009; Sánchez-Cuenca 2009a). Mariano Rajoy and José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero were once again the two principal candidates for prime minister. Zapatero returned a victory for the PSOE, validating the 2004 results in the eyes of many; yet the race was tight and the PP and PSOE both increased their support. There is some evidence to suggest that the PSOE picked up votes from the left and nationalist parties, and lost some of its centrist voters to the PP (Torcal & Lago 2008; Urquizu 2008). Most other parties lost support, including IU, Convergència i Unió (CiU, Convergence and Union), the Partido Nacionalista Vasco (PNV, Basque Nationalist Party), ERC and Coalición Canaria (CC, Canary Island Coalition).

What is perhaps surprising is that neither the 2004 (Van Biezen 2005; Oñate & Ocaña 2005) nor the 2008 elections (Torcal & Lago 2008) stand out at a systemic level from the characteristics of the cycle of elections that began in 1993. Aside from the anomalous elections of 2000, these characteristics include ‘high levels of competition and very tight victories, decreasing volatility, 75 per cent turnout and higher levels of party vote concentration’ (Torcal & Lago 2008, p. 374). After the first two democratic elections in 1977 and 1979, Spanish national elections were characterised by a severe lack of competition between the two principal parties, Alianza Popular (AP, Popular Alliance), which was renamed Partido Popular in 1989, and the PSOE. They were separa...