This is a test

- 414 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This volume covers the period 1787-1795 and contains The Defence of Usury, the Manual of Political Economy in its authentic form and two financial treatises which reflect Bentham's work to find a way in which govenment could be carried on without taxation.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Jeremy Bentham's Economic Writings by Werner Stark in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

THE PHILOSOPHY

OF

ECONOMIC SCIENCE

[I]

PHILOSOPHY is never more worthily occupied, than when affording her assistances to the economy of common life: benefits of which mankind in general are partakers, being thus superadded to whatever gratification is to be reaped from researches purely speculative. It is a vain and false philosophy which conceives its dignity to be debased by use.

[II]

A cloud of perplexity, raised by indistinct and erroneous conceptions, seems at all times to have been hanging over the import of the terms art and science. The common supposition seems to have been, that in the whole field of thought and action, a determinate number of existing compartments are assignable, marked out all round, and distinguished from one another by so many sets of natural and determinate boundary lines: that of these compartments some are filled, each by an art, without any mixture of science; others by a science, without any mixture of art; and others, again, are so constituted that, as it has never happened to them hitherto, so neither can it ever happen to them in future, to contain in them any thing either of art or science.

This supposition will, it is believed, be found in every part erroneous; as between art and science, in the whole field of thought and action, no one spot will be found belonging to either to the exclusion of the other. In whatsoever spot a portion of either is found, a portion of the other may be also seen; whatsoever spot is occupied by either, is occupied by both: is occupied by them in joint tenancy. Whatsoever spot is thus occupied, is so much taken out of the waste; and there is not any determinate part of the whole waste which is not liable to be thus occupied.

Practice, in proportion as attention and exertion are regarded as necessary to due performance, is termed art. Knowledge, in proportion as attention and exertion are regarded as necessary to attainment, is termed science.

In the very nature of the case, they will be found so combined as to be inseparable. Man cannot do anything well, but in proportion as he knows how to do it: he cannot, in consequence of attention and exertion, know anything but in proportion as he has practised the art of learning it. Correspondent therefore to every art, there is at least one branch of science; correspondent to every branch of science, there is at least one branch of art. There is no determinate line of distinction between art, on the one hand, and science on the other; no determinate line of distinction between art and science, on the one hand, and unartificial practice and unscientific knowledge, on the other. In proportion as that which is seen to be done, is more conspicuous than that which is seen or supposed to be known: that which has place is apt to be considered as the work of art: in proportion as that which is seen or supposed to be known is more conspicuous than anything else that is seen to be done, that which has place is apt to be set down to the account of science. Day by day, acting in conjunction, art and science are gaining upon the abovementioned waste—the field of unartificial practice and unscientific knowledge.

Whilst, as to the arts and sciences of immediate and those of more remote utility, it would not be necessary, nor perhaps possible, to preserve between these two classes an exact line of demarcation. The distinctions of theory and practice are equally applicable to all. Considered as matter of theory, every art or science, even when its practical utility is most immediate and incontestable, appears to retire into the division of arts and sciences of remote utility. It is thus that medicine and legislation, these arts so practical, considered under a particular aspect, appear equally remote in respect to their utility with the speculative sciences of logic and mathematics.

[III]

Directly or indirectly, well-being, in some shape or other, or in several shapes, or all shapes taken together, is the subject of every thought, and object of every action, on the part of every known Being, who is, at the same time, a sensitive and thinking Being. Constantly and unpreventably it actually is so: nor can any intelligible reason be given for desiring that it should be otherwise.

This being admitted, Eudæmonics, in some one or other of the divisions of which it is susceptible, or in all of them taken together, may be said to be the object of every branch of art, and the subject of every branch of science. Eudæmonics*—the art, which has for the object of its endeavours, to contribute in some way or other to the attainment of well-being—and the science in virtue of which, in so far as it is possessed by him, a man knows in what manner he is to conduct himself in order to exercise that art with effect.

Considered in the character of an edifice or receptacle, Eudæmonics may, therefore, be termed the Common Hall, or central place of meeting, of all the arts and sciences:—change the metaphor, every art, with its correspondent science, is a branch of Eudæmonics.

If the above observation be correct, it is only in one or other of two shapes or characters, viz. that of a source of happiness, or that of a security against unhappiness, that being can in any of its modifications, possess any claim to man’s regard.†

Eudœmonics being the name for the universally practised art— the pursuit of happiness,—being in some of its various shapes, will be allowed to be an indispensable means, without which the object of that art cannot in any instance be pursued and attained. Sensitive being is the only seat of happiness: being, in that and other shapes, is the universal instrument of happiness. To the attainment of happiness in any shape or degree, an acquaintance, more or less considerable, with the seat of happiness, and with such beings as, in each instance, afford a promise of serving in the character of instruments of happiness,—is more or less conducive, or even necessary. For the designation, of whatsoever portion of science may be regarded as capable of being attained, concerning being taken in its utmost conceivable extent,—the word Ontology has, for ages, been in possession of being employed.

Eudæmonics is the art of well-being. Necessary to well-being is being. In every part, therefore, of the common field,—concomitant and correspondent to Eudœmonics considered as an art, runs Ontology,*—considered as a science.

For the expressly declared subject of division, let us take the science: art and science running along every where together, every division performed on the one, may, on any occasion, be considered as applying to the other.

By means of this joint consideration, as often as, on looking at the name of a branch of art and science as it stands in the Table, we come to consider its nature, our attention will be pointed to the only source and measure of its value.

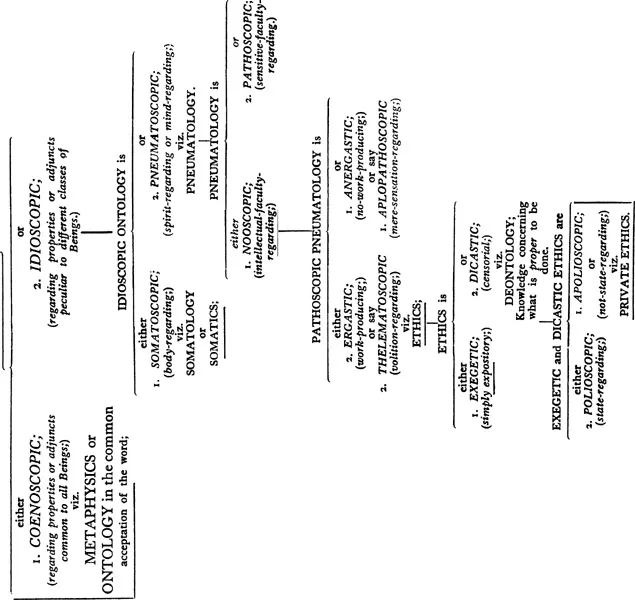

Coenoscopic† and Idioscopic‡—by successively attaching to the subject Ontology these two adjuncts, the field of art and science may thus be divided, the whole of it, into two portions; in one of which, viz. the coenoscopic, shall be contained the appalling and repulsive branch of science, to which the no less formidable, and to many a man intensely odious, appellation of metaphysics, is sometimes also applied: while to the other — viz. the idioscopic — all the other branches of art and science, may, without distinction, be consigned.

Division of Ontology into 1, Coenoscopic, and 2, Idioscopic.

Matter and mind—into these two portions, being in general, considered as an aggregate, is wont to be considered as divided. Hence arises,

Division of Idioscopic Ontology into Somatology,* or Somatics, and Pneumatology,† or Pneumatics, alias Psychology, or Psychics.

Division of Pneumatology into Alegopathematic‡ and Pathematoscopic.§

Alegopathematic, or say Alego-æsthetic Pneumatology has, for its single-worded synonym, the not unexpressive appellation Noology.*

It has for its subject spirit or mind, considered apart from all feeling, whether of the pleasurable or painful kind: considered that is to say with reference to the purely intellectual part of the animal frame: including simple perception, memory, judgment, reasoning, abstraction, imagination, &c.

Pathematoscopic Pneumatology may have for its synonym Pneumatic, or Psychological† Pathology.

Division of Pathematoscopic Pneumatology, or say Pneumatic or Psychological Pathology,‡ into Aplopathematic§ and Thelematoscopic.||

Aplopathematic Pneumatology has for its subject the aggregate of Pleasures and Pains of all kinds, considered apart from whatsoever influence, in the character of motives, the prospects of them may have upon the will or volitional faculty,—and the acts, as well purely mental and internal, as corporeal and external, of which those prospects may become the causes.*

Thelematoscopic Pneumatology, or Pathology, has for a synonym the single-worded appellative Ethics,† taken in its largest sense.

In the character of synonyms to Ethics are also used, in some circumstances, the words Morals and Morality.

First Division of Ethics (taken in the largest sense of the word) viz. into Dicastic,‡ i.e. Censorial, and simply Exegetic,§ i.e. Expository, or Enunciative. Dicastic, or Censorial, i.e. expressive of a judgment or sentiment of approbation or disapprobation, as intended by the author of the discourse, to be attached to the ideas of the several voluntary actions, (or say modifications of human conduct), which, in the course of it, are brought to view: in other words—his opinion, in relation to each such art, on the question—whether it ought to be done, ought to be left undone, or may, without impropriety, be done or left undone.

Simply Exegetic, i.e. Expository or Enunciative, viz. in so far as, without bestowing any such mark of approbation, disapprobation, or indifference, the discourse has for its object the stating what, in the opinion of the author, has, on each such occasion, actually come to pass, or is likely to have come to pass, or to have place at present, or to be about to come to pass in future,—i.e. what act is, on the occasion in question, most likely to have been done, to be doing, or to be about to be done.

ENCYCLOPEDICAL TABLE, or ART and SCIENCE TABLE:

Exhibiting the first lines of a Tabular Diagram of the principal and most extensive branches of ART and

SCIENCE, framed in the exhaustively bifurcate mode.

EUDÆMONICS

(From a Greek word, signifying the work of a good Genius, and thence felicity)

Is an all-comprehensive name, applicable to ART and SCIENCE in general, and thence to each and every branch of Art and Science, considered as conducive to WELL-BEING; wherein BEING is of course included. Having for its object, or end-in-view, WELL-BEING, as above—i.e. the existence of sensitive creatures—and that in a desirable state,—and for its subject BEINGS —i.e. creatures in general, considered as being—some of them receptacles or seats—all of them sources or instruments, of WELL-BEING,—it may, in a more particular manner, in so far as it is considered in the character of an ART, be termed, as above,

Eudæmonics: in which case, in so far as it is considered in the character of a Science, it may be termed ONTOLOGY.

EUDÆMONICS then, or ONTOLOGY, is

Exhibiting the first lines of a Tabular Diagram of the principal and most extensive branches of ART and

SCIENCE, framed in the exhaustively bifurcate mode.

EUDÆMONICS

(From a Greek word, signifying the work of a good Genius, and thence felicity)

Is an all-comprehensive name, applicable to ART and SCIENCE in general, and thence to each and every branch of Art and Science, considered as conducive to WELL-BEING; wherein BEING is of course included. Having for its object, or end-in-view, WELL-BEING, as above—i.e. the existence of sensitive creatures—and that in a desirable state,—and for its subject BEINGS —i.e. creatures in general, considered as being—some of them receptacles or seats—all of them sources or instruments, of WELL-BEING,—it may, in a more particular manner, in so far as it is considered in the character of an ART, be termed, as above,

Eudæmonics: in which case, in so far as it is considered in the character of a Science, it may be termed ONTOLOGY.

EUDÆMONICS then, or ONTOLOGY, is

The completion of this Table, as it now stands, having been posterior by about a twelvemonth to the printing of the letter-press to which it belongs,—in the interval some few changes aving presented themselves in the character of amendments, they are here inserted. But, of these alterations one consequence has of course been—a correspondent diversity, between the nomenclature employed in the body of the work and the nomenclature employed in this Table. A convenience had in the interval been found in giving to the termination—scopic (regarding) a more extensive application than in the first instance had been given to it.

This division has for its source the nature of the mental faculty, to which the discourse is immediately addressed. In so far as the discourse is of the Censorial cast, the faculty to which it addresses itself, and which, in so doing, it seeks to influence, is the volitional— the will, or at any rate the pathematic. In so far as it is of the simply Expository, or Enunciative, cast, the only faculty to which it immediately applies itself, viz. by seeking to afford information to it, is the intellectual faculty—the understanding.

For a synonym, Dicastic Ethics may have the single-worded appellative Deontology.*

The principle of division, deduced from this source, will be seen to be applicable, and accordingly applying itself, severally to all the following ones.

Division of Ethics (whether Expository or Dicastic) into Genicoscopic,† i.e. general matters-regarding; and Idioscopic,‡ i.e. particular-matters-regarding.

Synonyms to Genicoscopic, as applied to Ethics, are, 1. Theoretical; 2. Speculative. Synonyms to Idioscopic, as applied to Ethics, is the word practical.

In this, as commonly in other cases, the limits between general and particular not being determinate, so neither are those between what, on the one hand, is theoretical or speculative,—on the other, practical. Of the observations expressed, such part as is allotted to the explanation and fixation of the import of general words,—words of extensive import, the use of each of which is spread over the whole field, or a large portion of the whole field, of the art and science,— will belong mostly to the genicoscopic, theoretical, or speculative branch: and, under the name of principles, to the above observations will naturally be added any such rules, whether of the expository or the censorial cast, as in this respect are most extensive.

The deeper it descends into particulars, the more plainly it will be seen to belong to the idioscopic. In so far as, with the incidents exhibited in the fictitious narrative, any rules of a deontological nature (as in modern productions is frequently the case) happen to be intermixed, the matter of novels and romances comes to be included in, and the immense mass of it forms but a part of, the matter of PRACTICAL ETHICS.

Division of Ethics,—whether Exegetic or Dicastic, and whether Genicoscopic or Idioscopic,—into Apolioscopic,* i.e. political-state-not-regarding, viz. PRIVATE ETHICS—Ethics in the more usual sense of the word,—and Polioscopic i.e. political-state-regarding,† viz. GOVERNMENT,‡ alias POLITICS.§

[IV]

By a Pannomion, understand on this occasion an all-comprehensive collection of law,—that is to say, of rules expressive of the will or wills of some person or persons belonging to the community, or say society in question, with whose will in so far as known, or guessed at, all other members of that same community in question, whether from habit or otherwise, are regarded as disposed to act in compliance.

In the formation of such a work, the sole proper all-comprehensive end should be the greatest happiness of the whole community, governors and governed together,—the greatest-happiness principle should be the fundamental principle.

The next specific principle is the happiness-numeration principle.

Rule: In case of collision and contest, happiness of each party being equal, prefer the happiness of the greater to that of the lesser number.

Maximizing universal security;—securing the existence of, and sufficiency of, the matter of subsistence for all the members of the community;—maximizing the quantity of the matter of abundance in all its shapes;—securing the nearest approximation to absolute equality in the distribution of the matter of abundance, and the other modifications of the matter of property; that is to say, the nearest approximation consistent with universal security, as above, for subsistence and maximization of the matter of abundance:—by these denominations, or for shortness, by the several words security, subsistence, abundance, and equality, may be characterized the several specific ends, which in the character of means stand next in subordination to the all embracing end—the greatest happiness of the greatest number of the individuals belonging to the community in question.

Correspondent to the axioms having reference to security, will be found the principles following:—

1. Principle correspondent to security, and the axioms thereto belonging, is the security-providing principle.

A modification of the security-providing principle, applying to security in respect of all modifications of the matter of property, is the disappointment-preventing principle. The use of it is to convey intimation of the reason for whatever arrangements come to be made for affording security in respect of property and the other modifications of the matter of prosperity, considered with a view to the interest of ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 [The Philosophy of Economic Science]

- Chapter 2 Defence of Usury

- Chapter 3 Colonies and Navy

- Chapter 4 Manual of Political Economy

- Chapter 5 Analytical View [or] Summary Sketch of Financial Resources, employed and employable

- Chapter 6 Supply without Burthen; or Escheat vice Taxation

- Chapter 7 Tax with Monopoly

- Chapter 8 Proposal for a Mode of Taxation in which the Burthen may be alleviated or even ballanced by an Indemnity